Adopt a multidisciplinary approach and interpret images in a clinical context. That's the main advice of award-winning Spanish researchers who've attempted to provide clarity in cases of axial spondyloarthritis, or axial SpA.

Previously known as ankylosing spondylitis, axial SpA is a form of inflammatory arthritis where the main symptom is back pain, according to the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust website. Over time it can cause some of the bones in the spine to fuse together, making it less flexible, and it can also affect joints of the limbs (e.g., shoulders and knees), tendons, and ligaments.

The main differential diagnosis should be made with mechanical conditions, taking into account the spatial and temporary dissemination, noted Dr. Sara Sigüenza González and colleagues from the Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal in Madrid. The group's poster received a prestigious cum laude award at last month's RSNA meeting.

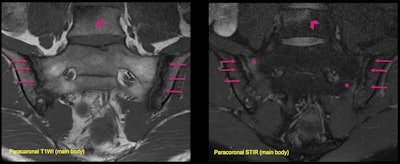

A 36-year-old man presented with lower back pain. Structural lesions are visible in paracoronal T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), including erosions and subchondral sclerosis (arrows). Paracoronal STIR in the same patient shows subchondral edema (asterisks), consistent with active inflammation. Note that the changes are bilateral and symmetrical, but more severe at the iliac sides of the joints. There is also an inflammatory Romanus lesion at the anterior corner of the L5 vertebral body (arrowheads) with an erosion and adjacent bone marrow edema. These findings together suggest ankylosing spondylitis. Remember to look at the main body for inflammatory disorders. All images courtesy of Dr. José Acosta Batlle et al and presented at RSNA 2023.

A 36-year-old man presented with lower back pain. Structural lesions are visible in paracoronal T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), including erosions and subchondral sclerosis (arrows). Paracoronal STIR in the same patient shows subchondral edema (asterisks), consistent with active inflammation. Note that the changes are bilateral and symmetrical, but more severe at the iliac sides of the joints. There is also an inflammatory Romanus lesion at the anterior corner of the L5 vertebral body (arrowheads) with an erosion and adjacent bone marrow edema. These findings together suggest ankylosing spondylitis. Remember to look at the main body for inflammatory disorders. All images courtesy of Dr. José Acosta Batlle et al and presented at RSNA 2023.

"In some difficult cases, we rely on looking for inflammatory and structural lesions, importance of injury location and biomechanics, correlation with all images available (x-ray/CT/MRI)," they stated, adding that if doubts persist, "look back later."

Bone marrow edema plays a central role in the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) axial SpA classification criteria. Radiologists should be careful when applying the ASAS classification criteria because bone marrow edema can also be found in early mechanical and degenerative changes, which are much more common than inflammatory disorders, they explained.

Identifying the type of BME pattern, other radiological features (bone erosion, ankylosis, or the spine disease), and awareness of the clinical picture can increase radiologists' diagnostic confidence and reduce overdiagnosis of inflammatory sacroiliitis. Knowledge of the anatomy and biomechanics of sacroiliac joints (SIJs) and spine, including anatomical variants and pitfalls, is also valuable.

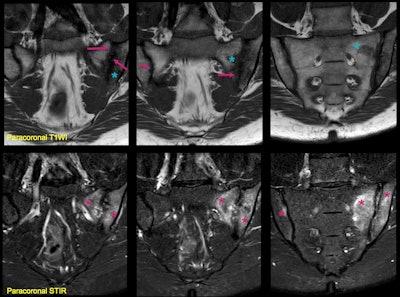

A 35-year-old woman presented with lower back pain, human leukocyte antigen B27+, and increased polymerase chain reaction. Paracoronal STIR shows extensive subchondral edema (asterisks) and increased signal intensity in the inter-articular line, reflecting effusion and synovitis in the left sacroiliac joint (SIJ); all consistent with active inflammation. Note that the changes are bilateral and asymmetrical with predominance of inflammatory changes in the left joint. Paracoronal T1WI shows structural including erosions, subchondral sclerosis (arrows), and early joint space loss. Note that some areas of osteitis/bone marrow edema are low signal in T1WI (blue asterisk), but not as low as sclerosis. Structural and inflammatory lesions can coexist, and SIJ involvement can sometimes be asymmetric or unilateral.

A 35-year-old woman presented with lower back pain, human leukocyte antigen B27+, and increased polymerase chain reaction. Paracoronal STIR shows extensive subchondral edema (asterisks) and increased signal intensity in the inter-articular line, reflecting effusion and synovitis in the left sacroiliac joint (SIJ); all consistent with active inflammation. Note that the changes are bilateral and asymmetrical with predominance of inflammatory changes in the left joint. Paracoronal T1WI shows structural including erosions, subchondral sclerosis (arrows), and early joint space loss. Note that some areas of osteitis/bone marrow edema are low signal in T1WI (blue asterisk), but not as low as sclerosis. Structural and inflammatory lesions can coexist, and SIJ involvement can sometimes be asymmetric or unilateral.

Some clues may exist about the difference between mechanical issues and inflammatory disorders, according to the authors. Subchondral BME in the SIJs is a common finding in both entities, so radiologists should be careful when interpreting.

It is also important to recognize the principal features of spondyloarthritis in x-ray, CT, MRI, and other imaging techniques and to keep aware of the general features and typical image findings in cases of spondyloarthritis, such as psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, enteropathy-associated arthritis, and undifferentiated spondylitis, they continued. Common pitfalls and differential diagnosis with other diseases that affect the axial bone are infection, amyloidosis, tumors, the development or occurrence of trauma, and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, a type of arthritis that affects tendons and ligaments, mainly around the spine.

Cases of subchondral sclerosis in mechanical load areas of the SIJ have these features: bilateral symmetrical/bilateral asymmetrical/unilateral; iliac facet and sacral facet; higher incidence in women than men, and in the 20-60 age group; increased incidence following pregnancy; joint space and articular surface are preserved; and exceptional erosions. Remember to look for continuous BME in the cartilaginous compartment, respecting the lower third, and bear in mind it can also affect the sacral facet, the researchers emphasized.

"Imaging pediatric SIJ is a challenge due to normal developmental changes in the immature skeleton," they stated.

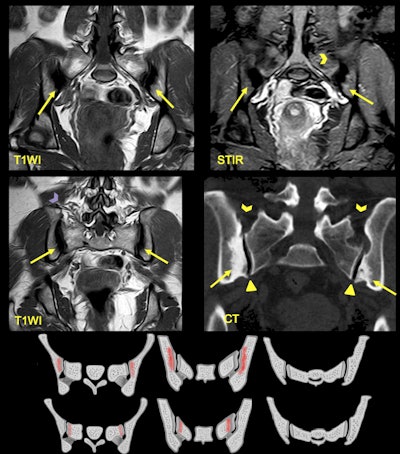

A 25-year-old woman presented with lower back pain and a history of two pregnancies. MRI shows areas of sclerosis (arrows) with low signal intensity on T1WI that arise along the iliac surface with bilateral and symmetric affection. CT shows triangular shape of the iliac bone sclerosis and lack of joint erosions. Note there is no joint space narrowing (triangle) in respect of the ligamentous compartment (arrowheads).

A 25-year-old woman presented with lower back pain and a history of two pregnancies. MRI shows areas of sclerosis (arrows) with low signal intensity on T1WI that arise along the iliac surface with bilateral and symmetric affection. CT shows triangular shape of the iliac bone sclerosis and lack of joint erosions. Note there is no joint space narrowing (triangle) in respect of the ligamentous compartment (arrowheads).

The authors urged radiologists to suspect sacroiliitis if the following are present: asymmetrical appearance, focal involvement or intense high signals; great intensity on the iliac side; and irregular erosions with sclerosis and/or fat metaplasia.