PET imaging can help reveal mechanisms underlying human consciousness and may play a pivotal role in improving the prognostication and treatment of severely brain-injured patients, Belgian authors have reported.

In a review, a group led by Dr. Leandro Sanz of the University of Liège discussed imaging techniques that could be useful tools for characterizing altered consciousness in patients with severe brain injuries. The team ultimately called for improved collaborations between researchers and clinicians to better translate these findings to the bedside.

"Major progress in brain imaging and clinical assessment have opened the door to a new era of postcoma care based on standardized neuroscientific evidence," the group wrote. The article was published on 3 February in the International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology.

With the development of mechanical ventilation in the 1950s, the ability to keep patients alive using artificial measures became a reality, and the family of disorders of consciousness was born, the authors wrote.

Since then, a unified diagnostic classification for disorders of consciousness has been progressively established and is still constantly evolving, and it is beginning to include measures derived from neurophysiology and neuroimaging, according to the researchers.

"The emerging evidence that a substantial fraction of clinically unresponsive patients is able to demonstrate residual brain functions compatible with (covert) consciousness has added new dimensions of complexity to this framework," they wrote.

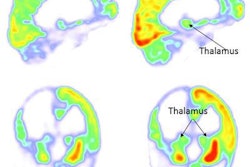

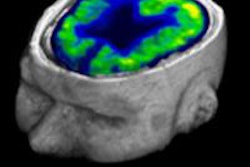

Sanz and co-authors, who included researchers from the university's Coma Science Group, noted that measuring brain glucose metabolism by PET can be used to characterize whole-brain or regional neuronal activity and assess residual function in key areas for consciousness, for instance.

Also, broad preservation of sleep-wake architecture and brain metabolism may be measured by PET in patients with covert consciousness, which is defined as consciousness that cannot be ascertained using bedside behavioral examinations, they wrote.

Moreover, residual brain activity at rest based on PET whole-brain metabolism constitutes another approach to detect consciousness. This method does not require the integration of external sensory signals by the brain, which may be impaired due to neurological lesions despite preserved conscious processing, according to the authors.

"These breakthroughs question the historical nomenclature and our current management of postcomatose patients," the authors wrote.

In addition to PET, the authors noted that qualitative or quantitative electroencephalogram and MRI-based diffusion tensor imaging may be used to predict long-term recovery of consciousness in postcoma patients.

Ultimately, while theorists are still actively debating the mechanisms that generate consciousness in the brain, clinicians faced with patients suffering from severe acquired brain injury need practical strategies to characterize altered consciousness and promote recovery, the researchers wrote.

"We advocate the creation of tight partnerships between research teams and clinical units to keep these tools sharp and translate the neuroscience of consciousness into better postcoma care," the authors concluded.