Since it hit early this year, the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically affected radiology in many countries in Europe, particularly Spain, Italy, and the U.K., according to a special session held on 17 July at ECR 2020.

Three radiologists from each of these countries shared with session attendees how their facilities were affected at the height of the pandemic's first wave, describing creative measures taken to provide the best possible patient care while also protecting physicians and staff from infection.

Spain

Dr. Marcelo Sánchez.

Dr. Marcelo Sánchez.Spain was inundated with COVID-19 cases and mobilized to make more beds available by turning exhibition halls and hotels into hospitals, said Dr. Marcelo Sánchez of Hospital Clinic of Barcelona. The country identified its first patient in late February; on 15 March, it locked down. Less than two weeks later, the first "medicalized" hotel opened. Between February and May, Spanish hospitals had more than 9,000 patients who presented to the emergency department and 2,400 hospitalized. Barcelona was the second most affected city in Spain after Madrid, Sánchez said.

Radiologists adapted their practice, using COVID-19-dedicated imaging equipment (CT, MRI, and ultrasound) and dividing into care groups to cover emergency and vascular/interventional services. They also shifted to working remotely. Of course, rates of thoracic imaging increased, with many chest x-ray and lung ultrasound exams performed at bedside. Thoracic CT also increased, particularly high-resolution CT and CT angiography.

Portable chest x-rays from a 69-year-old male with COVID-19 pneumonia. (A) Admission chest x ray with subtle bilateral interstitial opacities. (B) Three days later, x-ray showing bilateral peripheral airspace opacities characteristics of COVID-19 pneumonia. (C) Chest x-ray one month after admission with diffuse alveolar opacities compatible with Diffuse alveolar damage/acute respiratory distress syndrome in a patient with fatal evolution. Images courtesy of Dr. Marcelo Sánchez.

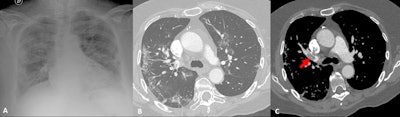

Portable chest x-rays from a 69-year-old male with COVID-19 pneumonia. (A) Admission chest x ray with subtle bilateral interstitial opacities. (B) Three days later, x-ray showing bilateral peripheral airspace opacities characteristics of COVID-19 pneumonia. (C) Chest x-ray one month after admission with diffuse alveolar opacities compatible with Diffuse alveolar damage/acute respiratory distress syndrome in a patient with fatal evolution. Images courtesy of Dr. Marcelo Sánchez. 70-year-old patient with COVID-19 pneumonia with radiologic improvement but clinical deterioration. CT angiography was performed. (A and B) chest x-ray and lung window from CT angiography showing bilateral peripheral reticular and ground-glass opacities suggesting COVID-19 pneumonia in resolution stage. (C) CT angiogram showing a pulmonary embolism in right upper lobe artery (arrow).

70-year-old patient with COVID-19 pneumonia with radiologic improvement but clinical deterioration. CT angiography was performed. (A and B) chest x-ray and lung window from CT angiography showing bilateral peripheral reticular and ground-glass opacities suggesting COVID-19 pneumonia in resolution stage. (C) CT angiogram showing a pulmonary embolism in right upper lobe artery (arrow).Sánchez estimated that his hospital is facing a backlog of 16,000 postponed imaging exams, 6,300 of which are CT, MRI, ultrasound, or angiography, not to mention the exams required to follow-up with COVID-19 patients.

"COVID-19 follow-up will also increase our waiting list," he said.

Italy

Italy was quite hard hit, said Dr. Nicola Sverzellati, head of the radiology unit at the University Hospital of Parma. The country's first patient, a 38-year-old man, presented at an emergency department in Codogno in February with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Only a few weeks later, the government locked Codogno and neighboring villages down. As the virus spread through the country, clinicians across Italy began tracking chest CT features of COVID-19, including ground-glass opacities, multilobe involvement, bilateral distribution, and posterior involvement.

Image A shows larger opacities rounded in shape and some consolidation with a halo of ground glass. This sign has been described in COVID-19 cases. Consolidation is also present in image B, but the consolidation looks a bit different with architectural distortion, consistent with an organizing phase of COVID-19 pneumonia. These show a later stage of pneumonia than in the first three examples. Image courtesy of Dr. Nicola Sverzellati.

Image A shows larger opacities rounded in shape and some consolidation with a halo of ground glass. This sign has been described in COVID-19 cases. Consolidation is also present in image B, but the consolidation looks a bit different with architectural distortion, consistent with an organizing phase of COVID-19 pneumonia. These show a later stage of pneumonia than in the first three examples. Image courtesy of Dr. Nicola Sverzellati.The University Hospital of Parma swung into action, increasing the amount of beds for COVID-19 patients from 100 in the first days of March to 900 by the third week of the epidemic, Sverzellati said. Old care pavilions of the hospital were reconditioned, and the facility connected to two other hospitals in the province that together offered more than 400 more beds.

Dr. Nicola Sverzellati is head of radiology at the academic hospital of Parma.

Dr. Nicola Sverzellati is head of radiology at the academic hospital of Parma."Apart from chest radiologists and body radiologists, any specialist or resident of the hospital was repurposed to serve [where needed], including making phone calls to patients' relatives," Sverzellati said.

The hospital also put together three mobile care units that included multidisciplinary teams of internal medicine, pulmonary, infectious disease, and radiology physicians; the units had portable ultrasound scanners, spirometers, blood gas analyzers, and swab test kits. More than 1,000 patients were treated via these units.

The epidemic has had a dramatic effect on routine or scheduled care, however, with 400,000 to 600,000 canceled surgical procedures and 12 million canceled or rescheduled imaging exams, Sverzellati said.

The U.K.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, there was initial concern in the U.K. about whether hospitals could handle a flood of patients, said Dr. Fergus Gleeson of Oxford University.

"The NHS [National Health Service] and radiology were unprepared, but measures were put in place very quickly," he said. "Radiology got very clear guidance from NHS, the Royal College of Radiology, the British Society of Thoracic Imaging, and local groups."

And as in Spain, the U.K. repurposed other facilities into hospitals: NHS Nightingale London converted the ExCeL conference center into a temporary site with a 4,000-bed capacity.

At Oxford, about 8,500 imaging exams have been postponed, Gleeson said. The Nightingale sites may be able to help with backlog, but it will be difficult.

"The Nightingale hospitals may be important resources to deal with backlogged imaging exams, which are on top of scans we'd normally be doing," he said. "We won't be able to go back to the work pace we had before COVID. In a post-COVID world, it takes longer to provide the same services."

Silver lining?

All three presenters were reluctant to ascribe any "benefits" to the first wave of the pandemic, but all did say that it has created a strong sense of teamwork in healthcare and that their facilities and networks are more prepared for any coming second waves of illness.

The COVID-19 crisis has not only made clear the importance of radiologists in the continuum of care, it has made clear just how crucial healthcare is, Gleeson noted.

"You only realize how important medicine is when you become ill," he said. "Otherwise, it's easy to take it for granted."