When a software-based, peer-review quality assurance (QA) and improvement program is implemented proactively, it can produce very impressive results, according to an award-winning electronic poster presented at the European Congress of Radiology (ECR) meeting last month in Vienna.

Real Time Medical, a Canadian-based software firm and provider of teleradiology services, described the software it developed to fulfill a provincial government contract. The contract required that 30,000 radiology examinations and associated reports be retroactively reviewed to assess the accuracy and completeness of each report, to make necessary changes, to incorporate the changes into the patients' medical records located at six different healthcare facilities, and to maintain a database that could provide a succinct, consolidated report of peer review findings.

The company subsequently commercialized the software. It also has been its own customer, using it to perform proactive peer-review QA among the radiologists it contracts to provide teleradiology services.

Dr. Nadine Koff.

Dr. Nadine Koff.

Real Time QA Improvement and Collaboration (QAIC) software was developed in response to the need to manage large-scale, multimember anonymized peer review and advanced workflow orchestration, president Dr. Nadine Koff told AuntMinnieEurope.com. When added to the company's flagship diagnostic exam sharing software (DiaShare) platform, QAIC supported the advanced workflows, orchestration, and workload balancing needed to deal with the large scale and tight time frames of its first, and then subsequent review projects.

QA improvement software requirementsRadiologists tend to view peer-review QA programs as being punitive, so it is imperative that any program initiative be a positive experience, positioned as a way to improve quality, patient safety, and overall radiologist performance. On-going continuous QA can help catch mistakes in a timely manner. It also must be designed so that it will not interfere with a radiologist's routine workflow or add an excessive workload burden.

"Anonymization of the radiologists being reviewed as well as the reviewing radiologist(s) is essential to avoid positive or negative biases. Peer review is inherently subjective and the radiology community small," she warned. "Confidentiality will encourage fair assessment and active participation."

Sampling rates should be adjustable and flexible, to optimize the effort and expense of surveillance relative to the likelihood of error, she explained. Types of exams that have low volume need only low level monitoring. Exams requiring complex reports may need greater scrutiny. So also may more work of individuals whose error rates are of concern.

Instant feedback increases confidence in the results as the reviewed radiologist has an opportunity to defend his/her assessment. In a clinical environment, there may be good and valid reasons for disagreements. This also provides an immediate and timely learning opportunity that can improve both future quality and accuracy.

"Peer review should enable radiologists to quantify their strengths and weaknesses over time," Koff emphasized. "A formal continuous quality assurance and improvement program will help even the best radiologists maintain their expertise and competence."

Use of the QAIC software, which was commercially introduced in November 2011 at the RSNA annual meeting, also has several additional applications. When a radiologist is absent or overburdened, it may be used to route exams for interpretation to others based on existing workload, specialization, or other criteria. It can be used to create a multisite pool for distributing on-call studies. It also facilitates the management of multicenter consultations or referrals. And it can be used to manage specialty networks of radiologists and other clinicians formed to deal with specific diseases or with programs that have the potential to be international in scope, she said.

Peer review radiologist at work. All images courtesy of Real Time Medical.

Peer review radiologist at work. All images courtesy of Real Time Medical.

The software needed to function across all radiology information systems and PACS platforms for interoperability, and it needed to be scalable to work with any sized configuration. It needed to support studies of all types of modalities. It needed to manage blinded, automated, and randomized sampling of exams in a PACS archive to prevent any type of bias when selecting studies for peer review. Additionally, the software needed to maintain anonymized peer review functions for all users.

In cases where one or more additional independent opinions were requested by a peer reviewer, the system had to be able to select second and third readers without bias, while maintaining the anonymity of all, and then collect, integrate, and manage second opinions and overread data. Supporting this functionality required automated tracking of aggregated results and the anonymized feedback to individual radiologists being reviewed. It also required the ability to integrate the clinical responses of radiologists whose work had been reviewed and commented upon, so that they could have the opportunity to formally respond if they felt the need to do so.

Finally, necessary changes in patients' radiology reports had to be added and properly documented. A database documenting the track record of all participants, both radiologists being reviewed and their reviewers, had to be automated and maintained, and a vast array of customizable metrics supported. All of this activity had to be integrated into the normal workflow of reviewer and reviewee radiologists to avoid any disruption.

Background of the initial project

In the ECR presentation, Koff explained that that QAI software platform was first used during a provincially mandated, retroactive review of a radiologist's work over a period of three years. Over a 60-day time frame, a team of 21 radiologists working remotely from multiple different jurisdictions carried out the review.

The accuracy of the diagnostic reports prepared by the radiologist who was being reviewed was quantified and benchmarked to that of the remote team. Deficiencies, which could have been identified in a timely manner and corrected if the program had been proactive, may be addressed by refresher training or mentorship.

Although Koff did not identify the client either during the ECR presentation or during a subsequent interview, she did not deny that the client was two regional health authorities of the Province of New Brunswick. The accuracy of a radiologist who worked in several hospitals of these health authorities had come into question. One of the health authorities had conducted its own review in July and August 2009 of 322 exams interpreted between 1 December 2008 and 9 February 2009. An interpretation error rate of 16% was identified, which seriously differed from an error rate of 3.5% that the health authorities considered to be "acceptable."

In October 2009, the health authorities held a press conference announcing that an independent, external review of exams read by the radiologist would be conducted. This would include a random sample of approximately 30,000 exams -- 18,000 from one health authority and 12,000 from the other -- that had been interpreted during 2006 through 2008. The sampling would include chest x-rays, ultrasound, mammograms, fluoroscopy, venograms, and Doppler ultrasound exams performed at five healthcare facilities.

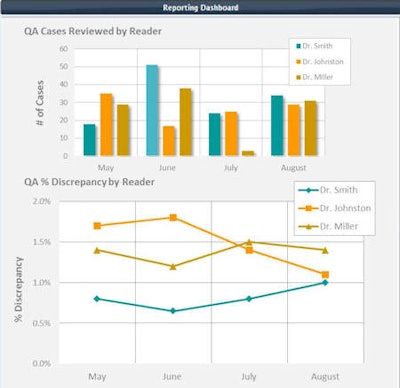

Example of a reporting dashboard..

Example of a reporting dashboard..Although the Ministry of Health of New Brunswick now operates a centralized image repository archive for the province, this was not operational when Real Time Medical was awarded the contract. All five facilities used the same PACS vendor (Agfa HealthCare), but exams were contained in two different PACS archives. Both hospital groups used the same radiology information system (Meditech), but had separate installations using slightly different versions of the RIS software.

The government contract required that the 30,000 exams be reinterpreted with a new report prepared for each and assessed for accuracy within a 60-day time frame. Koff stated that her company selected a team of radiologists to do this based on a community of peers approach, so that outcomes would accurately reflect reasonable expectations for a radiologist working in a similar practice.

"Participants needed to be members in good standing of their respective colleges, be actively practicing in both community and hospital settings, and be approved for licensing and practice in the jurisdiction of the review," she said.

Koff explained that "selection decisions about the number of exams, the modalities, and the exam mix were made by the local healthcare jurisdiction, and the rationale for these decisions was not disclosed. We worked with biomedical statisticians to arrive at a statistically relevant sampling rate. This proposed sampling rate was accepted by the jurisdiction requesting the review and applied to case selection for each relevant modality."

The company installed a PACS that was exclusively used for this project. All of the randomly selected studies were transferred from the two healthcare authority PACS archives to the company's DiaShare platform using DICOM transfer over a secure network. Previous reports were also transmitted electronically. On receipt of a study for review, the software automatically queried the PACS and retrieved any relevant prior studies.

The review study and its associated prior exams were matched with the skill set of each radiologist reviewer, and sent to them. The return of QA reports to the source PACS, for inclusion in a patient's electronic file, was also automatically managed by DiaShare's rules-based workflow orchestration and workload balancing engine. Additionally, if current clinical findings differed significantly from findings documented in the original report, the patient's referring physician was personally contacted to report the clinical discrepancies.

Quantifying the findings

The exam review had two process flows. After a peer-review report was prepared and returned to the "project PACS," it was compared with the original report. If there was no difference in interpretation, this information was recorded. If a discrepancy between the two reports was identified, the level of the discrepancy was rated, and the exam was assigned to a third reader. In proactive peer review, the exam might be sent to a radiology department's QA committee for review.

For the project, however, the accuracy of the diagnostic reports prepared by the radiologist under review was quantified and benchmarked to the remote team. Reports were categorized as either having no discrepancies, partial discrepancies, and significant discrepancies.

"Many of these discrepancies could be errors, but not necessarily," Koff said. "Occasionally, the differences in opinions could be challenged and debated, with the result of a majority opinion, rather than an absolute consensus.

She said that the project team focused on clinical impact, differentiating the discrepancies relevant to patient care. Their review was limited to the content, not the style, of the report. They used judgment on incidental findings, what the team dubbed "incidentalomas," that the reviewing radiologists would normally have mentioned in their own reports.

Overall, the review highlighted areas of weakness, which in a proactive setting could have been addressed in a timely, nonpunitive manner.

Based on the experience of the contract, Real Time Medical began to use the software to proactively perform peer review among the radiologists who provided the company's teleradiology services. The company also beta tested it with some hospital clients. Koff and colleagues presented what they learned from these experiences in their ECR poster.