Hyperpolarized xenon MRI can accurately identify abnormalities in the lungs of long-COVID patients who are experiencing breathlessness, U.K. researchers have reported.

Prof. Fergus Gleeson, chief investigator of the long-covid study. All images courtesy of National Consortium of Intelligent Medical Imaging.

Prof. Fergus Gleeson, chief investigator of the long-covid study. All images courtesy of National Consortium of Intelligent Medical Imaging.The EXPLAIN study, which involves groups in Oxford, Sheffield, Cardiff, and Manchester, is using hyperpolarized xenon MRI scans to investigate possible lung damage in long-COVID patients who have not been hospitalized with COVID-19 but who continue to experience breathlessness. The findings were posted on 29 January in the medRxiv preprint server.

"We knew from our post-hospital COVID study that xenon could detect abnormalities when the CT scan and other lung function tests are normal. What we've found now is that, even though their CT scans are normal, the xenon MRI scans have detected similar abnormalities in patients with long COVID," said Gleeson, head of academic radiology, director of the Oxford Imaging Trials Unit, and divisional director for the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust.

"These patients have never been in hospital and did not have an acute severe illness when they had their COVID-19 infection. Some of them have been experiencing their symptoms for a year after contracting COVID-19," he added.

There are now important questions to answer, such as the following: How many patients with long COVID will have abnormal scans? What's the significance of the abnormality detected and the cause of the abnormality? What are its longer-term consequences?

"Once we understand the mechanisms driving these symptoms, we will be better placed to develop more effective treatments," said Gleeson, past president of the European Society of Thoracic Imaging.

Development of xenon MRI

Hyperpolarized xenon MRI was pioneered by Prof. Jim Wild and the Pulmonary, Lung and Respiratory Imaging Sheffield (POLARIS) research group at the University of Sheffield, stated a press release issued by Oxford University Hospitals on 29 January. The team performed the first clinical research studies in the UK and the world's first clinical diagnostic scanning with this technology.

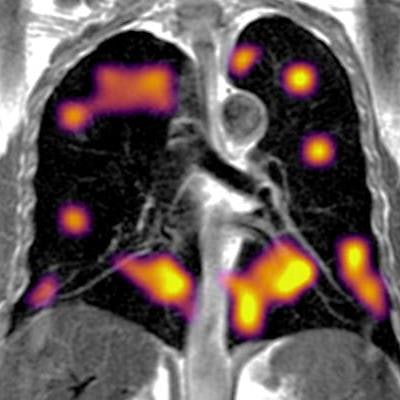

"Xenon MRI is uniquely placed to help understand why breathlessness persists in some patients post COVID. Xenon follows the pathway of oxygen when it is taken up by the lungs and can tell us where the abnormality lies between the airways, gas exchange membranes and capillaries in the lungs," said Wild, who is head of imaging and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Professor of Magnetic Resonance at the University of Sheffield.

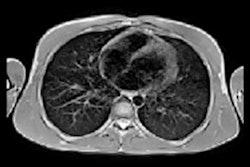

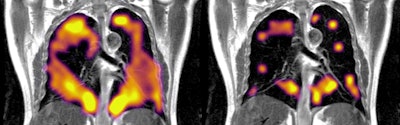

In the image on the right, the dark areas on a COVID-19 patient's xenon MRI scan may represent lung abnormalities. The left image is of a healthy patient.

In the image on the right, the dark areas on a COVID-19 patient's xenon MRI scan may represent lung abnormalities. The left image is of a healthy patient.The technique is a safe scanning test that requires the patient to lie in the MRI scanner and breathe in one liter of the inert gas xenon that has been hyperpolarized so it can be seen using MRI, Wild continued. As xenon behaves in a very similar way to oxygen, radiologists can observe how the gas moves from the lungs into the bloodstream. The scan takes just a few minutes, and because it does not require radiation exposure, it can be repeated over time to see changes to the lungs.

A previous study had used the same cutting-edge method of imaging to establish that there were persistent lung abnormalities in patients who had been hospitalized with COVID-19 several months after they were discharged.

While the full EXPLAIN study will recruit around 400 participants, this initial pilot had 36 people taking part, consisting of three groups. It included patients diagnosed with long COVID who have been seen in long-COVID clinics and who have normal CT scans, as well as those who have been in hospital with COVID-19 and discharged more than three months previously, who have normal or nearly normal CT scans and who are not experiencing long COVID.

There was also an age- and gender-matched control group who do not have long-COVID symptoms and who have not been hospitalized with COVID-19.

These initial results show that there is "significantly impaired gas transfer" from the lungs to the bloodstream in these long-COVID patients when other tests are normal, the authors wrote.

The full study will recruit 200 long-COVID patients with breathlessness, along with 50 patients who have had COVID-19 but now have no symptoms at all; 50 patients who have no breathlessness but who do have other long-COVID symptoms, such as "brain fog"; and 50 people who have never had long COVID who will act as controls for comparison.

Feedback on the results

"These are interesting results and may indicate that the changes observed within the lungs of some patients with long COVID contribute to breathlessness. However, these are early findings and further work to understand the clinical significance is key," commented Dr. Emily Fraser, the respiratory consultant who leads the Oxford Post-COVID Assessment Clinic.

Extending this study to larger numbers of patients and looking at control groups who have recovered from COVID should help us to answer this question and further our understanding of the mechanisms that drive long COVID, she noted.

According to Prof. Nick Lemoine, chair of NIHR's Long-COVID funding committee and medical director of the NIHR Clinical Research Network: "More than a million people in the U.K. continue to experience symptoms many weeks after infection, with breathlessness commonly reported. This early research is an important example of both the committed effort the U.K. research community is taking to understand this new phenomenon, and the world-leading expertise that community contains."

EXPLAIN is one of 19 studies that have received nearly 40 million pounds (47.9 million euros) from the NIHR to improve understanding of long COVID, from diagnosis and treatment through to rehabilitation and recovery.