While neurovascular compression syndromes may be best understood using certain MRI techniques, what to report of neurovascular contact on MRI in symptomatic patients has been in question, according to presenters in a special focus session February 26 at ECR 2025 in Vienna.

Certain anatomic and physiologic requirements are necessary to identify different cranial nerves affected by neurovascular conflict, according to Bernhard Schuknecht, MD, of the Medical Radiological Institute in Zurich, Switzerland, who, during his talk, analyzed imaging predictors and ways to improve the reliability of MRI prognostication.

Clinical manifestations of neurovascular compression syndromes can include unilateral stabbing, severe pain that comes and goes and can be triggered by light touch or wind. The symptoms can last less than two minutes each. MRI is used to confirm that there is neurovascular context, a space-occupying legion, or that there is none at all, Schuknecht explained.

One of three types of conditions may be suspected, based on the sites of neurovascular compression: trigeminal neuralgia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, or hemifacial spasm. Understanding these conditions, Schuknecht explained, dates back to 1932 when surgeons recognized mechanical compression involving a vessel at the trigeminal nerve as causing neuralgia.

For years, the treatment option was cutting the root to relieve the symptoms. Another treatment approach has been microvascular decompression surgery in cases of pharmaco-resistant symptoms, Schuknecht said.

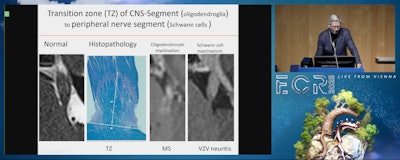

However, the location of vascular compression is clinically relevant, Schuknecht added, emphasizing homing in on the transition zone at the junction of the central myelinated segment and the proximal cisternal portion vulnerable to excitement by a pulsing artery.

"The terminology is inconsistent," Schuknecht noted, "but you have to keep in mind it's a transition zone central to peripheral myelin that makes the nerve susceptible to injury. The underlying pathology is not the vessel; it's demyelination. At this junction of oligodendroglia to Schwann cell myelination there is demyelination that makes this zone prone to injury." The length of the transition zone is also different with different cranial nerves affected, he added.

Neurovascular contact becomes a conflict when there is severe nerve impingement and deformity in the proximal cisternal portion of the transition zone, according to Schuknecht. This is classical trigeminal neuralgia. If there is a space-occupying legion or central demyelinating disease, this is secondary trigeminal neuralgia, and no nerve impingement or deformation is conveyed as idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia (See The changing face of trigeminal neuralgia, Maarbjerg, 2021).

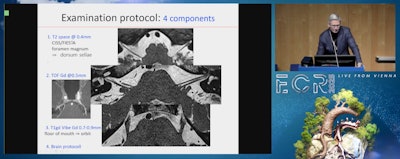

Schuknecht noted four components of the examination protocol, beginning with a T2 space CISS/FIESTA sequence at 0.4mm from the foramen magnum to the dorsum sellae, and including a gadolinium-enhanced TOF sequence.

Images courtesy of the ECR.

Images courtesy of the ECR.

Ultimately, Schuknecht recommended image fusion to distinguish the vessels from an artery.

"Contact is not enough; there should be indentation and displacement by an artery at the transition zone of the cranial nerve," he said, emphasizing that there will be correlation between the histopathological image and normal- to high-resolution MRI. "When you correlate to the pathologic image, it's the narrow segment that is the transition zone that is important to be analyzed for any neurovascular conflict."

"Definitive diagnosis of neurovascular conflict is difficult," Schuknecht explained. "Neurovascular contact on MRI is only relevant in patients with a clinical presentation. Clinical presentation should be a neurovascular compression, either in the distribution of the trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, or facial nerve. The pathological substrate is demyelination at the transition zone; the pathology is not caused by the vessel pulsation even though it is there primarily."

3D reconstruction aids in identifying the causative vessel and the degree of deformity, and is a means of communication to the surgeon as to the exact point of contact or conflict, Schuknecht said. The most common vessel involved in neurovascular compression is the superior cerebellar artery (in 60% to 90% of cases).

In addition, if the trigeminal nerve is reduced in diameter (the right side compared to the left) but there is no vascular compression, the signature is likely inflammatory. If there is vascular compression, this could be an unfavorable prognostic sign with respect to the surgical option, depending on the type of asymmetry, according to Schuknecht.

In terms of what should be reported from the MRI, Schuknecht suggested:

- Precise description of the vessels involved (single, multiple), anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA), venous components, for example

- Direction of impingement

- Additional findings such as arachnoid strands and nerve atrophy

All of this is important because treatment involves endoscopic surgery, Schuknecht said, adding that endoscopic microvascular decompression has evolved as an important treatment alternative in cases that are resistant to conservative treatment.

For more coverage from ECR 2025, visit our RADcast.