A specific set of CT protocols for trauma patients should be in place in every emergency department. That's the recommendation of Dr. Raffaella Basilico, emergency radiologist at University Hospital of Chieti in Italy.

"This will be useful for general on-call radiologists and residents who don't face trauma patients routinely," she told ECR Today, adding that radiologists should opt for multislice CT when evaluating a severe blunt abdominal trauma or polytrauma with a minor mechanism of injury.

The main cause of missed injuries, such as pancreatic and diaphragmatic lesions, bladder rupture, and pseudoaneurysms, is the presence of multiple more evident injuries, such as solid organ lesions, that become the focus of attention.

"Bowel injuries, for example, are often missed in CT examinations because in polytrauma patients some specific bowel findings can be misdiagnosed, such as the presence of free small air collections misinterpreted as normal intraluminal air," Basilico noted.

Left: Free air collection (arrow) close to the duodenum, misdiagnosed as normal intraluminal air. Right: One day later, the patient shocked, and a CT performed by means of oral contrast agent and by using bone window setting showed considerable amount of free abdominal air. Images courtesy of Dr. Raffaella Basilico.

Left: Free air collection (arrow) close to the duodenum, misdiagnosed as normal intraluminal air. Right: One day later, the patient shocked, and a CT performed by means of oral contrast agent and by using bone window setting showed considerable amount of free abdominal air. Images courtesy of Dr. Raffaella Basilico.Radiologists can overcome misdiagnosis by routinely using lung or bone window settings that help differentiate fat from air or multiplanar reconstructions, useful in vascular injuries and skeletal lesions. Moreover, a specific CT protocol for trauma patients, including unenhanced and multiphasic contrast-enhanced CT and, when necessary, a CT cystogram, will help radiologists detect an intra- and extraperitoneal bladder rupture in a case of multiple pelvic fractures, for example.

The management of trauma patients mainly depends on the mechanism and severity of the trauma, and getting it right first time can be a matter of life and death, if potentially fatal injuries are not detected within 24 to 48 hours from the first "hot" report.

Because the population is aging, general radiologists are likely to come across geriatric trauma in regular routine practice. In the recent past, geriatric patients were often "underimaged," and the severity of injuries was likewise underestimated. Older people don't always complain even when they are in significant pain, explain trauma experts. Furthermore, mechanisms that would cause bruising in younger healthy adults, such as falling from a chair or from standing, can cause fractures and dislocations in geriatric patients.

"We must bear in mind that seemingly minor mechanisms may result in major injury, therefore we should have a low imaging threshold for whole-body CT in the elderly," said Dr. Elizabeth Dick, consultant radiologist and lead for emergency radiology at London's Imperial College NHS Trust. "Trauma teams should avoid piecemeal CT, focusing solely on the injured area. If the patient is stable, a whole-body CT should be performed whenever there is suspicion of significant injury, and don't delay."

At her hospital, the target is for all stable trauma patients to be imaged within 30 minutes of admission.

"We often find numerous fractures from seemingly minor accidents. Despite a high scan rate in older patients, false-positive rates are low," noted Dick, who is also president of the British Society of Emergency Radiology.

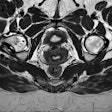

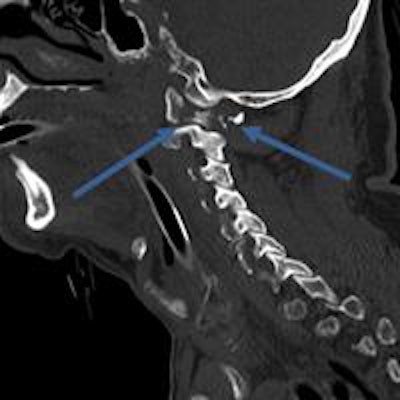

Everyday life can be more risky: A 70-year-old fell down stairs, causing a fracture of C1 ring. Image courtesy of Dr. Elizabeth Dick.

Everyday life can be more risky: A 70-year-old fell down stairs, causing a fracture of C1 ring. Image courtesy of Dr. Elizabeth Dick.Besides maintaining a high index of suspicion in elderly trauma patients, a deep knowledge of their injuries and syndromes can help radiologists avoid errors: There may be degenerative changes in the spine, such as central cord syndrome (CCS), bruising of the cord caused by compression of the canal space, usually undetectable on CT and requiring MRI.

Known as the "golden hour," the first 60 minutes after severe trauma represents the time frame within which definitive treatment should have started, and this includes the time span between injury occurrence and hospital admission, according to Dr. Stefan Wirth, vice chair for clinical radiology at Ludwig Maximilian University Hospital of Munich and president-elect of the European Society of Emergency Radiology.

"The faster you act, the more survivors you have. This is why time is a critical issue. Every institution should aim to provide CT scanning within 10 minutes. The processes of image reconstruction, reading, reporting, and distributing should also not exceed another 10 minutes," he said.

Above: CT head scan with increasing visibility of intracranial hemorrhage in the first few hours. Left: Unenhanced head CT; bleeding is hard to depict. Right: Control scan four hours after whole-body CT, and thus after contrast enhancement. Below: Images show traumatic rupture of the bowel. Images courtesy of Dr. Stefan Wirth.

Above: CT head scan with increasing visibility of intracranial hemorrhage in the first few hours. Left: Unenhanced head CT; bleeding is hard to depict. Right: Control scan four hours after whole-body CT, and thus after contrast enhancement. Below: Images show traumatic rupture of the bowel. Images courtesy of Dr. Stefan Wirth.Radiologists also need to include treatment planning with the surgeon and anesthetist when optimizing processes in polytrauma management.

"Find ways to measure quality in your institution. The most common problem is time. Measure it, detect reasons for delay and categorize them in terms of 'avoidable' und 'unavoidable,' then for the former, deliver strategies to avoid repeat occurrences. This optimization should be ongoing," Wirth stated.

He pointed to how the literature shows that prompt deployment of whole-body CT decreases death rates of treatable patients at high risk of death in the first two hours post trauma by about 25%, in effect saving every fourth life in that particular group.

Due to its many advantages that include a two-phase coverage of the upper abdomen, potentially yielding information about bleeding activity, Wirth's personal choice of protocol is positioning patients feet first with arms crossed over the abdomen. He then favors performing an unenhanced head scan and an aortal triggered arterial phase scan of the neck, chest, and upper abdomen, followed by a standard delay of 50 seconds portal-venous CT imaging of abdomen and pelvis. A first oral report can be provided five minutes after finishing the procedure.

However, very early stages of bleeding, especially in the brain, may be hard to detect, he cautions. Radiologists should be aware of possible hyperacute intracranial bleeding without tremendous density above the surrounding parenchyma.

"If in doubt, repeat the scan. In most cases when a second scan seems appropriate, limiting the procedure to particular organs is sufficient," he said.