The commoditization of radiology endangers the capacity of the specialty to maintain its hard-won central role in patient care. This is the view of Dr. Adrian Brady, consultant radiologist at Mercy University Hospital in Cork, Ireland, and first vice president of European Society of Radiology.

"To young radiologists I would say: make sure that you are part of the clinical team, that you are seen, and that you are a clinician first -- and a radiologist to support that clinical activity," he said in a recent podcast.

Brady also elaborated on his previous comments about how technological improvements have led to the phenomenon of the "vanishing radiologist." Spiral CT and other imaging advances have increased reporting workload, and digitization of reporting has created the expectation of almost-instantaneous report availability, all of which reduces the time radiologists spend with referrers and patients, he noted.

Dr. Adrian Brady, first vice president of the European Society of Radiology.

Dr. Adrian Brady, first vice president of the European Society of Radiology.Part of the problem lies in inadequate radiologist numbers, particularly in Ireland and the U.K., which lag behind Germany, France, and most other European countries, according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data.

However, even if more students could be recruited to radiology during medical school, the gap between training and deployment is so long that new generations of scanners and innovative techniques will be released in the interim, continuing to swell the workload. Radiologist numbers constantly seem far behind in attempting to keep abreast of increasing demand, he told RadCast presenters and co-founders, radiologists Dr. Uzoma Nnajiuba and Dr. Jamie Howie.

AI's multiple faces

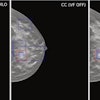

Workload may in part be offset by artificial intelligence (AI) tools taking on repetitive time-consuming tasks, such as looking for CT lung nodules, microcalcifications in breast imaging, or polyps in CT colonography. AI will probably also influence radiologists' work in other ways, but it will not make radiologists redundant, according to Brady.

"A practice that has taken 120 years to develop as a specialty won't be reduced to 1s and 0s or algorithms. A few years ago, medical students were asking if they should bother considering entering radiology as a specialty. Now they are no longer asking me that," he said.

In fact, U.K. radiology training numbers are increasing each year, which would suggest that AI is being viewed as a tool rather than a replacement for the radiologist, the presenters noted. But its role in radiology is ever-increasing and this will be reflected in a larger AI program at ECR this year and next year, with hands-on workshops so that participants can see the capacity of applications.

AI might also become a substantial means of delivering radiology training, Brady continued.

"I can imagine a scenario where, for example, after AI detects a probable hepatocellular carcinoma on MRI, it automatically diverts the study for interpretation to trainees that the system recognizes as needing training in this area," he said. "Previously a lot of time would have been spent with the trainer and trainee interpreting images together. With AI, 80% of this could be replaced by training on the digital tool, with 20% reserved for more valuable face time."

AI could also allow for the development of a hybrid specialty, with pathologists and radiologists working together. Over the past six years, such a merger between radiology and pathology (as a united diagnostic department) has taken place at the University of Geneva, Switzerland. AI could also be leveraged to potentially incorporate genomics and radiomics into the work of such merged diagnostic departments.

Think quality, not quantity

In the podcast, Brady also explained why radiology research needs to move from lower-end research on technical and diagnostic efficacy toward assessing imaging's contribution to patient outcomes and society at large.

Papers published recently by the Lancet Oncology Commission have made some attempt to address radiology's value and contribution at the societal level, he said. These articles studied imaging availability and its impact on cervical cancer in countries across the world, and on a broader basis, they looked at the effects of imaging availability in general on life expectancy and disease outcome in 200 countries worldwide.

"It's difficult to do, but that's the kind of research we need to be doing more of," he said.

Brady illustrated how more could be done, with an example from his own career. When he first started working as a radiologist, there was no such thing as fast CT, and CT pulmonary angiography didn't exist.

"With the development of spiral CT, then multislice spiral, CT pulmonary angiography became normal and easier to do. But the number of patients investigated for possible pulmonary emboli has gone through the roof, as have the numbers of pulmonary emboli that we're identifying. But what is the impact of that? I'd love to find some way of looking at the true mortality rate for pulmonary emboli in 1990 compared to the present day, to see what the value of being able to diagnose these emboli actually is," Brady said.

Indeed, with more people on anticoagulation medicine, and more head CTs being done for anticoagulated patients who have suffered head injuries, it could be a negative for society, noted the presenters.

Brady concurred, adding that these were the sort of complex issues that needed to be examined.

"We've put huge resources into CT pulmonary angiography which has led to more diagnoses. But these diagnoses lead to utilization of yet more resources. It's something that needs to be analyzed," he said.

From volume to value

Worldwide figures over the past four to five years, reveal that medical inflation (at 7% to 8%) is greatly in excess of average cost-of-living inflation (at 2% to 3%). In 1970, U.S. health expenditure was about 6% of gross domestic product, but now it's about 18%. In Europe it was 5%, now it's about 11%, he noted.

"Radiologists are conscious of the fact that we can't just keep on doing more and more MRI and CT; we have to ensure that a limited set of resources is used to the best possible advantage so that, as far as possible, everything we do is meaningful," Brady noted.

The value-based radiology (VBR) movement, which started about 15 years ago in the U.S., isn't about suddenly changing what radiologists do but ensuring that it is recognized, as well as -- in an era of rising demand and limited resources -- about providing more value without spending more money, he continued. VBR is also designed to change the view of radiology as a "cost" and one that potentially should be minimized. It helps funding bodies see how radiology contributes to personal value delivered to individual patients and to value to society, as a whole.

"Essentially, it's about advocating for our specialty, educating users (patients and referrers) and about educating and lobbying the funders of our specialty to support us in best use of a finite resource," he said. "We've been chasing volume for years. We need to bring a halt to this and make sure that what we do with our resources is appropriate and helpful."

The RadCast team. From the left: Drs. Muhammad Khan, Uzoma Nnajiuba, and Jamie Howie. RadCast is a series of podcasts developed by clinical radiology trainees on a mission to provide a grassroots perspective.

The RadCast team. From the left: Drs. Muhammad Khan, Uzoma Nnajiuba, and Jamie Howie. RadCast is a series of podcasts developed by clinical radiology trainees on a mission to provide a grassroots perspective.You can listen to the full podcast and others on the RadCast Anchor page or by searching for RadCast on Spotify, Google, or Apple Podcasts.