Evidence of the broad range of cardiovascular and pulmonary complications caused by cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulants, opioids, and cannabis has been evaluated by authors based in Spain and the U.K. They've outlined the precise role of imaging in these patients in an article posted on 23 July by the European Journal of Radiology (EJR).

"Clinical presentation is often nonspecific and a history of drug intake may not be readily available. Therefore, imaging plays an important role in detecting and characterizing these complications," Dr. Adrià Roset-Altadill, from the Institute of Diagnostic Imaging at Girona University Hospital, and colleagues from Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital noted. "Knowledge of the various cardiopulmonary imaging manifestations of recreational drugs allows the radiologist to make an early diagnosis and aid in timely management."

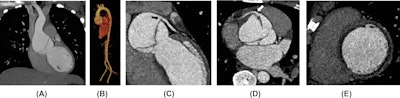

Cocaine-related aortic dissection. A 28-year-old man with a history of cocaine consumption presented with severe chest pain. (A) Thoracic aorta coronal CT angiogram reveals a dissection flap within a dilated aortic root. (B) 3D CT aortic angiogram reconstruction demonstrates isolated aortic root involvement without extension to the remaining aorta. (C and D) ECG-gated coronary CT angiogram reformats illustrate the dissection flap running from the aortic valve to the sinus level and extending into the left main coronary artery (black arrow). The right coronary artery was also affected by the dissection (white arrow). (E) ECG-gated coronary CT angiogram in a short-axis view shows diffuse subendocardial hypodensity concerning associated myocardial ischemia. All images courtesy of Drs. Adrià Roset-Altadill, Monika Radike, Dennis Wat and EJR.

Cocaine-related aortic dissection. A 28-year-old man with a history of cocaine consumption presented with severe chest pain. (A) Thoracic aorta coronal CT angiogram reveals a dissection flap within a dilated aortic root. (B) 3D CT aortic angiogram reconstruction demonstrates isolated aortic root involvement without extension to the remaining aorta. (C and D) ECG-gated coronary CT angiogram reformats illustrate the dissection flap running from the aortic valve to the sinus level and extending into the left main coronary artery (black arrow). The right coronary artery was also affected by the dissection (white arrow). (E) ECG-gated coronary CT angiogram in a short-axis view shows diffuse subendocardial hypodensity concerning associated myocardial ischemia. All images courtesy of Drs. Adrià Roset-Altadill, Monika Radike, Dennis Wat and EJR.

Cardiovascular complications include myocardial infarction, endocarditis, aortic dissection, infectious pseudoaneurysm, retained needle fragments, cardiomyopathy, and pulmonary arterial hypertension, while pulmonary complications encompass pulmonary edema, crack lung, pneumonia, septic emboli, barotrauma, airway disease, emphysema, and excipient lung disease. Awareness of the imaging manifestations along with the clinical history and a high grade of suspicion enable an accurate diagnosis and appropriate management plan, they explained.

"Imaging explorations are fundamental for detecting and characterizing the manifestations of recreational drugs, although injury patterns frequently overlap, and it is often difficult to know the exact cause," the authors continued. "These injuries are related to the type of consumed drug, the method of drug administration, or the associated impurities and fillers."

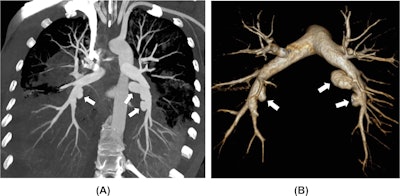

A 35-year-old woman with a history of multiple drug abuse presented with general discomfort, fever, chest pain, cough, and massive hemoptysis. Blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus anginosus, but no signs of endocarditis were found on echocardiography. (A) CT pulmonary angiogram maximum intensity projection (MIP) reformatting shows multiple pulmonary artery saccular outpouchings (white arrows) within the consolidated lower lobes. (B) 3D CT pulmonary angiogram reconstruction better depicts the saccular dilatations of the inferior lobar pulmonary arteries in keeping with infectious pseudoaneurysms (white arrows).

A 35-year-old woman with a history of multiple drug abuse presented with general discomfort, fever, chest pain, cough, and massive hemoptysis. Blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus anginosus, but no signs of endocarditis were found on echocardiography. (A) CT pulmonary angiogram maximum intensity projection (MIP) reformatting shows multiple pulmonary artery saccular outpouchings (white arrows) within the consolidated lower lobes. (B) 3D CT pulmonary angiogram reconstruction better depicts the saccular dilatations of the inferior lobar pulmonary arteries in keeping with infectious pseudoaneurysms (white arrows).

Cocaine is a potent sympathomimetic agent that can be found in two fundamental forms: powder cocaine, which can be taken orally, intravenously, or sniffed; and smokable cocaine, called freebase or crack, which is considered to be more addictive, they wrote. Cardiopulmonary complications after cocaine abuse are common and diverse, with myocardial infarction and pulmonary edema or hemorrhage being the most frequent.

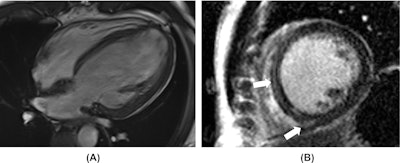

Amphetamine-associated cardiomyopathy. A 42-year-old man with a known history of amphetamine consumption presented with heart failure symptoms. (A) Cardiac MR four-chambers SSFP image in an end-diastolic phase reveals a severely dilated left ventricle. Functional analysis showed a severely decreased left ventricular ejection fraction. (B) Short-axis late gadolinium enhancement slice depicts faint septal mid-wall and lower insertion point fibrosis (white arrows).

Amphetamine-associated cardiomyopathy. A 42-year-old man with a known history of amphetamine consumption presented with heart failure symptoms. (A) Cardiac MR four-chambers SSFP image in an end-diastolic phase reveals a severely dilated left ventricle. Functional analysis showed a severely decreased left ventricular ejection fraction. (B) Short-axis late gadolinium enhancement slice depicts faint septal mid-wall and lower insertion point fibrosis (white arrows).

Cannabis' main component is tetrahydrocannabinol, famous for its psychotropic effects, the researchers pointed out. "Depending on the concentration of this cannabinoid, there are different types of recreational drugs: marijuana, an herbal compound that is usually smoked; hashish, a dried resin that can be smoked or ingested; and hash oil, the strongest product. Complications of cannabis consumption are generally restricted to the lungs, with emphysema, airway disease, and barotrauma being the most common."

Thermal injury to the trachea with subsequent stenosis may happen during freebase cocaine inhalation due to highly inflammatory solvents, while small airway disease and asthma exacerbation are frequent consequences of cocaine, heroin, and marijuana smoking, they noted. Smoked cocaine and heroin produce airway mucosa stimulation and inflammation, potentially leading to bronchoconstriction. Imaging manifestations include bronchial wall thickening, patchy parenchymal opacities with tree-in-bud nodularity, and mosaic attenuation.

"Cannabis smoking exerts an irritating effect on the bronchial mucosa, resulting in mucus hypersecretion and inflammation-triggered edema. These airway inflammatory changes manifest on CT with bronchial thickening, bronchiectasis, and mucoid impaction," the authors wrote.

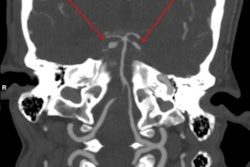

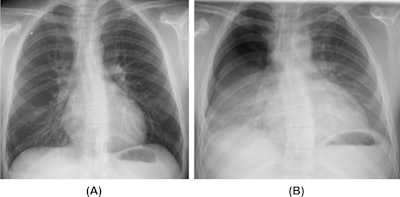

Barotrauma in a cannabis smoker. A 21-year-old man who is a habitual cannabis smoker presented to the emergency department with right-sided sudden chest pain and dyspnoea. (A) Inspiratory posteroanterior chest radiograph reveals a small right superior pneumothorax. (B) Expiratory posteroanterior chest radiograph better demonstrates the right-sided pneumothorax.

Barotrauma in a cannabis smoker. A 21-year-old man who is a habitual cannabis smoker presented to the emergency department with right-sided sudden chest pain and dyspnoea. (A) Inspiratory posteroanterior chest radiograph reveals a small right superior pneumothorax. (B) Expiratory posteroanterior chest radiograph better demonstrates the right-sided pneumothorax.

The impact of illicit drug use is a priority healthcare topic, and more attention to this area is needed in terms of public and staff education and more research to enhance prevention and improve outcomes, Roset-Altadill and his colleagues told AuntMinniEurope.com in a joint statement sent by email on 24 July. Other areas of interest would be to evaluate if there are any correlations between radiology findings and patient symptomatology, physiological findings (such as spirometry), responses to pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments, and validated quality-of-life scores, they added.

"Ideally, acknowledging the variations in populations and related socioeconomic factors, it would be useful to conduct prospective studies in specific drug user groups to study the outcomes and mitigating factors," they noted.

Among the unanswered questions are: How can we optimize community services to help prevent recreational drug abuse, educate the public, and spot the use complications promptly? Has the inception of community respiratory case finding and management clinics in the drug and alcohol addiction services led to a reduction in unplanned care utilization (e.g. emergency department attendances)? Can primary care medical records improve case findings? Which clinical presentation features can point towards the diagnosis? As several radiology findings can overlap with other diseases, which are the patterns or combinations of patterns that can aid timely management? In the multidisciplinary team, what's the role of the radiologist to prevent, diagnose, and treat diseases?

"We would like to propose this topic as education and/or scientific sessions to the planning committees of upcoming congresses, and we encourage our colleagues to conduct studies in their areas and submit their work," the authors pointed out.

You can access the full EJR article here. (Cardiovascular and pulmonary complications of recreational drugs: A pictorial review, by Adrià Roset-Altadill, Monika Radike, and Dennis Wat, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2024.111648)