How can breast cancer screening facilities adapt to pandemic-era restrictions while ensuring that at-risk patients don't miss out on vital screening exams? What future measures will benefit the most vulnerable? An ECR Overture roundtable discussion on 2 March addressed these and other questions.

Breast screening exams in Austria dropped by around 30% during the pandemic, and this was exacerbated by the reluctance of patients to attend screenings once facilities opened again, noted session moderator Prof. Dr. Michael Fuchsjäger, chairman of the European Society of Radiology (ESR) Board of Directors. The Austrian Ministry of Health and scientific groups launched campaigns to get patients back into screening centers.

Screening experts from across Europe got down to business during Wednesday's ECR Overture discussion.

Screening experts from across Europe got down to business during Wednesday's ECR Overture discussion.During the roundtable discussion, Fuchsjäger applauded the U.K.'s decision to switch from booked appointment times to telephone appointments. The U.K. is also not currently inviting women over 70 for screening, and many facilities have focused on medium- to high-risk patients.

"When invited women made their own appointments, this boosted attendance from 70% to nearly 100% at the screening session avoiding wasting mammography slots," explained Prof. Fiona Gilbert, president of the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI). "In the past, a third of women would change their allotted appointments and even then, only 80% would attend. The change made more work for office staff, but they got on board with it to make the appointment system more efficient."

She also noted that, anecdotally, women were happier attending screening sessions in mobile vans rather than in hospital settings. Roundtable panelist and speaker Prof. Evelien Dekker, professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Amsterdam UMC in the Netherlands, concurred that screening outside the hospital has worked better for colorectal cancer screening as patients felt safer and there were fewer constraints.

Prof. Dr. Boris Brkljačić, past ESR President, noted that in Croatia screening was initially delayed by two months at the start of the pandemic and even patients with diagnosed breast cancer delayed their surgery by up to a year for fear of COVID-19. However, while mobile screening might be part of the solution for a pandemic program, there are other aspects of screening and management that must take place in hospitals, such as more complex imaging and core biopsies.

"COVID has been a learning curve for screening strategists to tailor their programs for future pandemics," he noted.

Smart screening

Home screening using blood biomarkers could be the answer, noted Fuchsjäger. Blood biomarkers are being tested at scale by commercial companies looking at profiles to pick up on solid tumors. During the pandemic, these companies have sent kits to patients for home testing, he said.

Prof. Dr. Michael Fuchsjäger from Graz in Austria.

Prof. Dr. Michael Fuchsjäger from Graz in Austria."If the sample is large enough then in theory, you can do home testing for blood biomarkers, but will it pick up on cancers early enough to impact mortality?" Gilbert noted.

"We know it can pick up on late and large cancers but there is not enough evidence that it allows early detection. However, going forward, it would really help for triaging patients," she added.

In response to a question on what else could be done for future screening, both Dekker and Gilbert responded that a smarter approach could be used with better targeting of women who are most likely to develop breast cancer and benefit from earlier detection.

"We're worried about the people who will die from killer cancers so we should be thinking about to whom we should offer more frequent screening, and screening more smartly. When a program is so disrupted, this is the time to think about how to do screening better across Europe," Gilbert said.

Need for resources

A large increase in screening resources across Europe is essential to rapidly catch up with missed patients and will hopefully result in minimal impact on cancer mortality, she pointed out. Rapid vaccine rollout, social distancing, and mask-wearing have allowed health services to resume normally.

EUSOBI and other groups continue to model and monitor the adverse effects of delays in screening rounds to pressure policymakers to provide additional resources. She noted that symptomatic services need to be as efficient as possible with no delay for patients, and this means ensuring that there is sufficient capacity to immediately manage patients attending the clinic with pain, lumps, or other symptoms.

When breast cancer screening clinics were closed at the start of the pandemic, only patients with symptoms such as lumps were prioritized for full investigations, she said. When screening centers reopened in mid-May to June 2020, backlog was an issue and centers operated at lower capacity due to social distancing rules, requirements to systematically clean equipment, staff illness, and patient reluctance to attend.

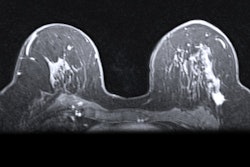

However, European centers first invited patients at high and medium risk undergoing yearly MRI screening to make sure they got their screening as close to when they should have had it. At the same time, other strategies were discussed, stated Gilbert.

Prof. Fiona Gilbert from Cambridge, U.K. Photo courtesy of the Royal College of Radiologists.

Prof. Fiona Gilbert from Cambridge, U.K. Photo courtesy of the Royal College of Radiologists.Because modeling estimates showed that the increased intervals would result in more incidence of faster-growing cancers going undetected, this raised the question of who should be targeted in the catch-up invitations. Should the focus be on younger women in whom cancers tend to be faster growing and therefore more likely to be missed due to an increased screening interval -- or on older women in whom more cancers are found? Most countries didn't change their age-group screening strategies in their recovery plans and maintained pre-COVID protocols for the age groups in question, she explained.

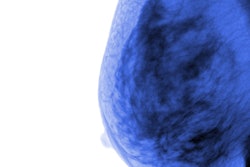

The next strategy broached was whether or not patients with dense or very dense breast tissue should be prioritized in catch-up invitations, but a lack of automated density measurement tools in place in many countries prevented wide-scale adoption.

However, prepandemic studies on density are in place. In the Netherlands, women with dense breasts are offered MRI and will be also offered contrast-enhanced mammography in a new trial, and in the U.K., a similar trial (BRAID) randomizes patients to four arms in order to compare standard of care with abbreviated breast MRI, or automated breast ultrasound or contrast-enhanced spectral mammography.

Elsewhere, the European Union-funded MyPeBS (My Personal Breast Screening) trial is looking at determining breast cancer risk and the need for more or less frequent screening intervals through a questionnaire and analysis of genetic material and breast density. This is intended to stream women to screening annually, every two years, or every four years.

Screening delays

Gilbert noted that the U.K. screening program was delayed by three to four months from March to June 2020 as services paused in the first wave of COVID across Europe. In some countries, screening intervals increased from two years to three years. Based on modeling from different countries and scientific data, the long-term outcomes of late diagnosis are greater incidence of larger cancers and more interval cancers.

For example, the Australian modeling study of a six-month delay estimated a 5% shift of cancers from stage 1 to stage 2, while a 12-month delay would reduce five-year survival from 91.4% to 89.5%. In Holland, a six-month delay was estimated to result in an additional two breast cancer deaths per 100,000 women screened and 186 extra breast cancer deaths over 10 years. While in Italy, modeling estimated that with a 4.5-month delay, there would be 3,324 delayed cancer diagnoses. A three-month delay would mean 10,000 women would not be diagnosed, and a six-month delay would mean that 16,000 women would not be diagnosed.

Aiming to support screening through the crisis, the U.K. government invested in the program to increase capacity with additional staff and facilities to allow catch-up, she said.