A U.K. position statement published on 9 February has highlighted evidence gaps for routine follow-up brain tumor imaging. The authors hope it will pave the way for progress in evidence-based imaging.

"For too long, follow-up imaging of brain tumors has been performed as a considered opinion rather than a timetable based on science," lead author Dr. Tom Booth, PhD, consultant neuroradiologist at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "A large group of experts were motivated to make a position statement to articulate the status quo and use it as a springboard for good research, which will allow a timetable based on science."

The document has been published in the open-access journal Frontiers in Oncology. It originated from a meeting held in London in April 2019 that was attended by representatives of all U.K. stakeholders to determine an approach to interval imaging of adult brain tumors. Charity representatives, neuro-oncologists, neurosurgeons, neuroradiologists, neuropsychologists, trialists, health economists, data scientists, and the imaging industry were all represented. It was held in conjunction with a National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Brain Tumour group workshop.

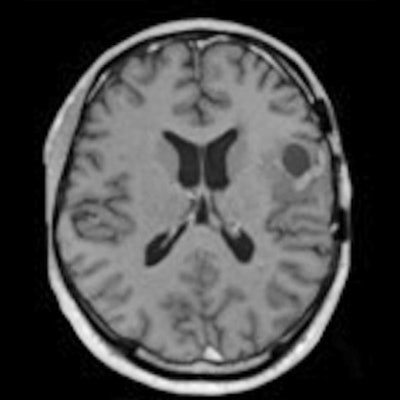

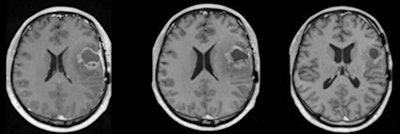

The figure shows longitudinal imaging after treatment. The timing of the scans is a practical solution to assess treatment response, but the approach is not evidence-based and the images do not always give a definitive correlate as to whether the tumor is responding to treatment. We do not truly know if we image too often, too little, or the right amount in terms of morbidity (including quality of life), mortality, and cost-effectiveness, Dr. Tom Booth, PhD, said. Courtesy of Dr. Tom Booth, PhD.

The figure shows longitudinal imaging after treatment. The timing of the scans is a practical solution to assess treatment response, but the approach is not evidence-based and the images do not always give a definitive correlate as to whether the tumor is responding to treatment. We do not truly know if we image too often, too little, or the right amount in terms of morbidity (including quality of life), mortality, and cost-effectiveness, Dr. Tom Booth, PhD, said. Courtesy of Dr. Tom Booth, PhD.Clinicians tend to use brain scans at predetermined times to assess if a brain tumor patient is responding to treatment, but scanning frequency can range from every few weeks to every few months. Different countries and hospitals use different approaches, but it is a real problem to determine the best approach based on science.

"I felt there was a real need to look at this and Dr. Robin Grant, a neurologist with an interest in adult brain tumors, suggested the best format would be through an Incubator Day," Booth explained. "We explored the status quo and looked at how to gather future evidence."

Gaps in the evidence

The position statement describes why brain imaging is a relatively neglected area, and the authors highlight the holes in the evidence and explore ways to gain the essential knowledge.

Early adult brain tumor research has always focused on therapeutic clinical trials, and imaging was an "add on" to the clinical trials and seen as a practical solution to the problem of trying to assess whether the treatment is working or not, according to Booth.

"Like much of radiology (and medicine), the rationale for such patient management based on imaging has never been rigorously scrutinized: This is often because it is challenging to do so," he commented. "An additional reason to not question the status quo is because it has become so hard-wired into routine practice and current clinical trials that it would be a considerable challenge to redesign interval imaging if the evidence showed that current interval imaging practices are not fit for purpose."

More collaborative efforts are now required to make progress, Booth continued.

"This is because the treatment complexity and relative rarity of brain tumors requires as much data and information to be pooled as possible," he said. "There are multiple collaborations looking at different aspects of the patient pathway -- typically from a therapeutic or surgical angle. In terms of imaging, radiologists typically tackle one area at a time."

An important example here is the study called "Improving Treatment of Glioblastoma: Distinguishing Progression From Pseudoprogression," where more than 10 U.K. facilities are collaboratively collecting prospective imaging and clinical data. The organizers hope this government-supported, machine-learning collaborative experience will be used to tackle the bigger question of optimizing the entire imaging pathway.

In addition, there are some U.K. databases on the horizon that may be promising, including BRIAN (retrospective data) and MATRIX (prospective data).

Global relevance

The project started as a U.K. focused position statement and included all U.K. brain tumor charities, so there was no overseas participation, but Booth is convinced the initiative will be of interest and relevance to overseas colleagues.

"Clearly the type of healthcare system is likely to influence interval imaging practice through, for example, the type of national reimbursement system," he said. "As such, the statement incorporated global evidence -- as the references will attest -- and is written in a way to be used globally with comment on different healthcare systems."

The recommendations for future study are not didactic and are common to a range of healthcare systems, he added.

Overall, Booth hopes the global imaging community will make use of the statement. The recommendations for future study are of value to everybody, and they are common to a range of healthcare systems. The wide range of future studies suggested, and how they might build the required body of evidence, are particularly relevant to all researchers in this field, according to Booth.

"Clearly pathways need to be optimized so we scan the right patient at the right time with multiple downstream clinical benefits: this is true before, during, and after COVID," he said. "However, COVID-19 has clearly made radiologists and other clinicians question the evidence behind all their activity more as the risk-benefit of attending for a scan has currently changed."