Radiologists must become COVID-19 symptom-aware and remain vigilant at all times, especially as the second wave takes root, leading thoracic radiologist Dr. Sam Hare said in a Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) webinar on the evening of 12 November. He also described how imaging has taken center stage when it comes to COVID-19 diagnosis.

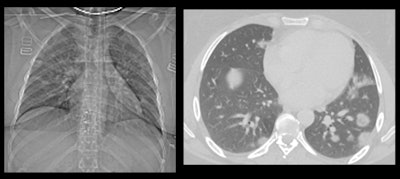

Particular care is essential if a patient presents with abdominal pain, he said, citing the example of a patient who presented at his own hospital with what appeared to be classic appendicitis symptoms. When scanned, the patient showed no signs of appendicitis, but a chest x-ray revealed lung abnormalities that were consistent with COVID-19 infection.

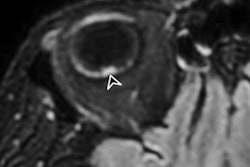

This patient had fever and abdominal pain for seven days and appeared to have appendicitis. The surgeon reported that the patient had no COVID-19 symptoms, but a radiologist correctly diagnosed COVID-19. All images courtesy of Dr. Sam Hare.

This patient had fever and abdominal pain for seven days and appeared to have appendicitis. The surgeon reported that the patient had no COVID-19 symptoms, but a radiologist correctly diagnosed COVID-19. All images courtesy of Dr. Sam Hare."The patient had COVID-19 without having any shortness of breath, and only abdominal pain," noted Hare, who is a consultant chest radiologist at the Royal Free London National Health Service (NHS) Trust and the National Specialty Advisor for Imaging for NHS England. "So patients with abdominal pain and diarrhea can have COVID-19 and that's really important to recognize."

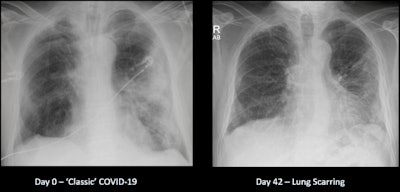

Lung fibrosis after COVID-19 can be particularly worrisome, and he indicated that "even if there's 20% to 30% of cases that result in potential lung scarring, 20% to 30% of half a million people is a far bigger number and a far bigger resource burden on the health service than 20% to 30% of 10,000 patients."

Initial experiences

Hare recalled his surprise when reading his first x-ray of patients with COVID-19.

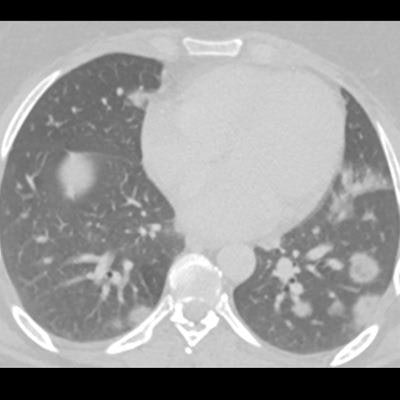

"This was a male patient in his 60s who was admitted to hospital in March 2020 with fever and shortness of breath. I was asked for my opinion on the x-ray by a respiratory physician, and as soon as I looked at it, my initial reaction was: 'Oh, wow, what am I looking at here?' It looked very unusual compared to what I would usually expect to see in a standard chest infection," he said.

Hare only recognized the image as COVID-19 because it was very similar to cases that he had been reading about in medical journals. He felt particularly proud of the interpretation of the x-ray by a radiologist because it informed the clinicians that this was a COVID-19 diagnosis -- despite the patient having a negative COVID-19 swab test. "That's very important because it shows the powerful role of imaging in determining fever in patients. Now we often get asked what a COVID lung actually looks like."

Dr. Sam Hare.

Dr. Sam Hare.At the start of the pandemic, Hare said that his department was "seeing case, after case, after case." He described how, ordinarily, he might see one or two chest x-rays showing pneumonia in his daily workload. During the surge of the pandemic, he saw 40 to 50 cases of COVID-19 on x-rays and CT, making it a very difficult time, he noted.

In an effort to maintain control of infection and limit cross-contamination of areas, radiographers would move the mobile x-ray imaging machines into the accident and emergency department or to wherever the patients were. Every patient who needed an imaging test for their COVID-19 had one, and that is the untold story of the pandemic, according to Hare, who is a member of the executive committee of the British Society of Thoracic Imaging and an advisor to the RCR.

An added complexity is the shortage of radiologists in the U.K. "We're battling a new disease in a global pandemic. We are relying on rapid x-ray and CT reporting, with not many radiologists, so you can start to see just how resources are constrained and how difficult things are."

Which modality for COVID-19?

One of the main questions radiologists had to answer was whether to use CT or x-ray in the first instance. In the early days of the pandemic, radiologists referred to the studies that were conducted on passengers who developed COVID-19 on the Diamond Princess cruise ship, which docked off the coast of Yokohama, Japan, he explained. It is important to remember that of those passengers who tested positive for COVID-19, approximately 70% were asymptomatic, and of those who were asymptomatic, some had abnormal CT scans with a white, "misty lung" appearance, yet nearly half of patients had completely normal scans.

"This is why CT and COVID-19 is a bit of a minefield and is a difficult judgment to make," he added.

Hare explained how a CT scan was entirely normal and showed well-defined black lungs in certain patients who had COVID-19, particularly early on in the infection. This was the reason why, later on in the pandemic, the standard x-ray became an important diagnostic tool to triage the severity of patients' illnesses and manage patients while awaiting the results of the formal swab tests.

MRI is not of great use for looking at the air sacs of the lungs, but it can be quite good for looking at blood vessels in the lungs, he said. "With COVID-19 being a pneumonia and primarily looking at the air sacs of the lungs, it just doesn't give you the resolution or the definition of the actual architecture of the lung to provide any information about lung scarring. ... It's very dependent on movement and you don't see the lungs very clearly, but with a CT scan, we can see pristine appearances of the lung."

Once radiologists became more familiar with the image presentation of COVID-19 in the lungs, they were able to identify and categorize the images as indeterminate, non-COVID-19, or normal. Furthermore, U.K. radiologists shared their images across the NHS digital platform to enhance learning in other radiology departments. Speedy reporting of the images across departments in hospitals was vital to ensure the ongoing care and management of patients, and radiologists worked through the night to ensure this was done, Hare explained.

Long COVID-19 and the lung

A significant proportion of patients do get some significant lung scarring, and many hospitals are organizing post-COVID-19 meetings to specifically follow up these patients.

Recovery from COVID-19 can be a long road.

Recovery from COVID-19 can be a long road."The lungs take a long time to recover in those patients, which is not the case for a chest infection," he continued. "Usually, chest infections have cleared by six weeks at the latest, whereas we're seeing COVID patients six months on who still have some mild lung damage; they feel short of breath when they're doing even mild activity like going for a walk."

The lung scarring/fibrosis leads to a distortion of the lung, preventing effective oxygenation of the blood to those areas of damage and resulting in fatigue and lethargy and an inability to exercise. "Patients may be tired for a particularly long time, and the concerning thing is lung scarring is irreversible, so patients may have that for the rest of their lives."

While the presence of antibodies could signal that a patient may have had COVID-19, it cannot be relied upon as an indicator of disease, as in the case of Hare's own personal experience.

"I myself tested positive for coronavirus, and months later I had antibody tests and I tested antibody negative. I felt just not quite right for weeks and weeks, but only had a very mild illness and had a normal x-ray," he said.