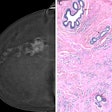

A team of British researchers known for past criticism of screening mammography is arguing that the design of the U.K.'s Age Extension Trial of Breast Cancer Screening (AgeX) is flawed. The group believes evidence from the trial should not be used to justify extending breast screening beyond existing age ranges, according to an analysis published online on 10 April in BMJ.

The trial's structure is at fault, wrote lead author Dr. Susan Bewley of King's College London and colleagues. Its evidence base was shaky, its outcomes measures were inadequate, and its design made it vulnerable to bias.

"It is good practice for scientific experiments to be preceded by a systematic review of the evidence to avoid wasteful research and repeating unnecessary harms. Here, there was no such review," the authors wrote.

"During the past decade, AgeX increased its planned duration and sample size, study outcomes were changed, and a proposal for statistical analysis was retrospectively appended," they added. "These factors, coupled with the protocol's stated plan to continue the trial beyond a 'fixed, predetermined sample size' until 'clear answers emerge' all increase the likelihood of a biased assessment."

Fatal flaws?

The U.K.'s current breast cancer screening protocol is to offer mammography every three years to women between the ages of 50 and 70. It has been estimated that the U.K.'s screening program prevents 1,300 deaths from breast cancer per year.

Bewley, however, has been one of the leading critics of breast screening in the U.K. In 2018, for example, she led a group of mammography opponents who wrote a public letter advocating that women who were believed to have been passed over for their final round of breast screening due to a computer glitch should forgo getting follow-up screening exams. Instead, these women should only seek help if they experience symptoms of breast cancer, the group wrote.

In the current article, Bewley and colleagues downplay mammography's contribution to mortality reduction, believing that the decline in breast cancer deaths is because of improved treatment.

"Evidence suggests improvements in breast cancer survival rates since the introduction of mass screening probably result from concurrent improvements in the adjuvant hormonal and chemotherapy used to treat breast cancer," the group wrote. "There is also evidence that screening does not reduce the number of tumors reaching late stage and that it results in substantial overdiagnosis, with consequent radiotherapy, lumpectomies, and mastectomies."

The AgeX trial was conducted between 2010 and 2016 to explore the potential risks and benefits of expanding the National Health Service (NHS) breast cancer screening age range in England. The intention was to offer one extra mammogram to women between the ages of 47 and 49 and up to three to women older than 70.

But it was a flawed trial, lacking explicit, fully informed consent, Bewley's team wrote. Women were not educated about the potential harms of mammography screening, from psychological distress to overdiagnosis.

"Early AgeX trial documentation refers to 'so-called overdiagnosis.' But the team's assumption that overdiagnosis was unimportant was challenged in 2012 when the Independent U.K. Panel on Breast Cancer Screening ... published a detailed review of the evidence," the authors wrote. "The report recognized and quantified overdiagnosis -- for every breast cancer death averted, three 'cancers' that would never have troubled women during their lifetimes would be found and treated. The physical and psychological harms resulting from such treatment are substantial. Yet in 2016, when AgeX's recruitment target was raised to 6 million, this increase -- with corresponding potential for harm -- was not referred to or justified."

The trial also did not make explicit the balance of risks and harms for mammography screening in women older than 70, according to the authors.

"Older women are less able to tolerate surgery than younger women because of increased likelihood of comorbidities, so overdiagnosis and overtreatment have a greater effect on their quality of life and physical function," Bewley and colleagues wrote.

Real consequences

The financial and human costs of AgeX will include extra general practitioner visits, physical and psychological harms from diagnoses of cancers that would not necessarily affect women in their lifetime, increased workload on the NHS breast screening program, and the burden of extra treatment on the NHS, according to the team.

Study participants must be fully informed when participating in research, especially when risks are unclear, Bewley and colleagues concluded.

"We call on the investigators and verifiers of any data resulting from AgeX to use all-cause death as the primary outcome," the group wrote. "An independent inquiry into the scientific quality, governance arrangements, and ethical issues arising from the trial would inform future high standards for the design and conduct of government-run trials."