A new study from Northern Ireland has demonstrated that risk-stratified breast cancer screening works, increasing cancer detection threefold. The authors are optimistic their data will lead to long-term improvements in tailored screening services.

"The general breast screening program in the U.K. of women aged 50 to 70 with no risk factors has a cancer detection rate of approximately eight per 1,000. This risk-stratified screening program has a cancer detection rate of 25.3 per 1,000 screens," lead author Dr. Eddie Gibson told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "There is plenty of research on risk-stratified breast screening, but as yet I am not aware of any published outcomes from a screening program such as this anywhere in the world."

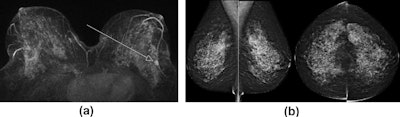

Screening MRI and mammogram in a 45-year-old woman with the BRCA2 mutation. (a) Maximum-intensity projection, contrast-enhanced, subtracted T1-weighted MRI shows a stippled background enhancement with a 10-mm type III enhancing nodule in the left lower outer quadrant. (b) Mammography demonstrates dense tissue and benign nodularity, which is essentially normal. Mastectomy revealed a 14-mm grade II invasive lobular carcinoma. Images courtesy of Gibson et al and Clinical Radiology.

Screening MRI and mammogram in a 45-year-old woman with the BRCA2 mutation. (a) Maximum-intensity projection, contrast-enhanced, subtracted T1-weighted MRI shows a stippled background enhancement with a 10-mm type III enhancing nodule in the left lower outer quadrant. (b) Mammography demonstrates dense tissue and benign nodularity, which is essentially normal. Mastectomy revealed a 14-mm grade II invasive lobular carcinoma. Images courtesy of Gibson et al and Clinical Radiology.The higher-risk screening program in the U.K. is still relatively new and not well known, he explained. Increased awareness of its availability and more knowledge of its effectiveness will hopefully lead to more eligible women being referred to their local service, noted Gibson, a consultant radiologist at Northern Trust Antrim Area Hospital, north of Belfast. He is also quality assurance lead of the Northern Ireland Breast Screening Programme.

Higher-risk breast screening commenced in Northern Ireland in April 2013, so relatively little is known about expected cancer detection rate, recall rates, and attendance rates. In an article published online on 29 May in Clinical Radiology, the researchers studied four years of data, from 2013 to 2017. The group used screening data and standards from the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP) as a baseline for comparison.

Startling results

In the general screening program, implemented in 1988, women ages 50 to 70 in Northern Ireland are invited for mammographic screening every three years. In 2016 and 2017, across four screening units, 81,882 women were invited, with 77.1% attending screening. The recall rate for assessment was 3.9%. Cancer detection was 6.5 per 1,000 screened.

In the higher-risk program, 28 cancers were detected over the four screening years using mammography only (13 cases), MRI only (four cases), and a combination of mammography and MRI (11 cases). These 28 cancers were detected from a total of 1,107 screening episodes, yielding an average of 25.3 cancers detected per 1,000 screens, compared with 6.5 per 1,000 detected in the general program.

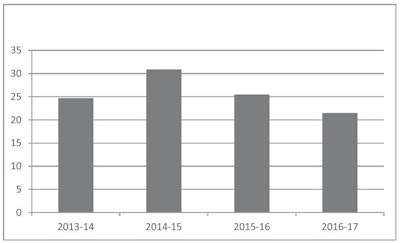

The cancer detection rate varied each year over the four years, ranging from 21.5 (2016-2017) per 1,000 women screened to 30.9 (2014-2015). Although the authors suggested an expected cancer detection rate of more than 20 in this higher-risk cohort, they stressed that larger numbers of screened women over a longer time frame are needed.

Cancer detection rates per 1,000 screens for 2013-2017 in higher-risk screening program. Image courtesy of Gibson et al and Clinical Radiology.

Cancer detection rates per 1,000 screens for 2013-2017 in higher-risk screening program. Image courtesy of Gibson et al and Clinical Radiology.Recall rates also improved year on year from an initial 14.2% in 2013-2014 to 8.6% in 2016-2017. This was most likely due to increased reader experience in MRI interpretation and the evolution of a new screening program, which gradually leads to balancing of prevalent and incident screens, the authors noted.

The study also showed a growing trend in attendance rates, which increased from 68.9% (162 attended/235 invited) in 2013-2014 to 77.7% (372/479) in 2016-2017, with a dip in attendance to 62.6% (259/414) in 2014-2015 and a rise to 70.4% (314/446) the following year. Attendance figures for 2015-2017 were above the acceptable threshold for the NHSBSP, the group stated.

In the future, all breast cancer screening may be risk-stratified, says Dr. Eddie Gibson.

In the future, all breast cancer screening may be risk-stratified, says Dr. Eddie Gibson.This first venture into risk-stratified screening has proved highly successful, detecting three times as many breast cancers, according to Gibson. However, more data are needed to understand the full benefits.

"Women at moderate and high risk of breast cancer are managed outside the NHSBSP according to NICE [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence] guidelines," he noted. "Therefore, there is little national data on the outcomes of screening women in this cohort. Perhaps the NHSBSP should take ownership of these other at-risk groups to quality assure their screening and allow accumulation of bigger datasets to see how effective screening can be for these women."

Risk-stratified screening may represent the future for all screening programs, and this should lead to improved cancer detection that may significantly offset perceived harms in people of known increased risk of developing cancer, he continued.

"I hope these outcomes will inspire more research into risk-stratified cancer screening and the data provided can be used as a benchmark leading to improved standards," he said.

The RCR's response

Dr. Caroline Rubin, RCR's vice president of clinical radiology.

Dr. Caroline Rubin, RCR's vice president of clinical radiology.The article by Gibson and colleagues demonstrates that stratified high-risk screening can be undertaken with reasonable recall rates for assessment and excellent cancer detection rates, according to Dr. Caroline Rubin, vice president for clinical radiology at the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) and a consultant radiologist at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

"This should provide reassurance that too many women are not being recalled unnecessarily. The cancer detection rates are as expected for this high-risk group," she stated. "Ideal next steps would be to study long-term survival rates in this particular population, to see if screening not only picks up more cancer but also saves more lives in this high-risk group."