Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies can help overcome many of the current challenges facing liver surgery and, ultimately, may optimize decision-making and treatment planning, according to new research from a leading French facility.

The group, led by senior author Dr. Patrick Pessaux, PhD, from Strasbourg University Hospital in France, reviewed more than 1,000 publications exploring various potential applications of VR and AR in medicine. Focusing specifically on the clinical studies relevant to liver surgery, they found that the highly realistic and interactive nature of VR and AR helped clinicians improve their diagnosis and therapeutic planning, as well as facilitated actual surgery (Surgical Oncology Clinics, January 2019, Vol. 28:1, pp. 31-44).

"The use of VR and AR navigation systems has shown a potential clinical utility, especially in cases of complex liver surgery," the authors wrote. "Preoperative simulation of the surgical procedure and accurate user-friendly calculation of the future liver remnant can significantly decrease improper surgical procedures and postoperative complications."

VR bolsters presurgical planning

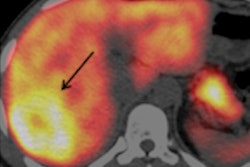

Imaging has long played a key role in liver procedures because of the organ's complex anatomy and the intricate requirements for clinical decision-making, the authors noted. Traditional volume rendering has provided clinicians with a 3D view of patient-specific anatomy, but the images are not interactive and not well suited for assisting surgery.

"Advanced imaging, such as virtual and augmented reality, may help to overcome some of these challenges and optimize diagnosis and strategic therapeutic planning," they wrote. The combination of VR and AR "enables a deep understanding of the anatomy and can show anatomic variants and complex anatomic relationships that may be missed on conventional DICOM imaging."

VR software is capable of generating 3D models of patients' CT or MRI scans that clinicians can visualize on a monitor or with a head-mounted device.

In their analysis, Pessaux and colleagues identified 17 clinical studies published between 2001 and 2016 that used this application of VR technology for the preoperative planning and simulation of hepatobiliary oncologic surgery. Among a total of 740 patient cases, surgeons reported successful tumor resection for approximately 89% of the cases. Preoperative planning with VR for these cases was consistently associated with high accuracy in terms of predicting the volume of healthy and cancerous tissue that eventually was resected.

Furthermore, VR demonstrated a capacity to provide critical information about liver anatomy that led to changes in surgical strategy. In one of the studies examined, for example, Tian et al claimed to alter their surgical management strategy for two cases of hepatocellular carcinoma. Examining the tumors surrounding the hepatic vein in VR allowed them to determine that surgical resection was indeed feasible, where conventional imaging indicated otherwise.

On average, Pessaux and colleagues found that surgeons changed the status of a liver cancer from resectable to unresectable in 67% of cases by looking at patients' medical images in VR after an initial examination of 2D images.

The primary feature limiting the more widespread use of VR for liver surgery is the amount of time needed to create patient-specific VR models, the authors noted. The mean value of creation time is 32.1 minutes, with a range of 5.1 to 75 minutes.

"Despite the overall low level of evidence of the published literature regarding the contribution of 3D VR to surgery today, VR planning has been reported as an important method in predicting resected liver volume compared with standard imaging ... with important implications on decision-making regarding resectability and choice of operative strategy," they wrote.

AR improves surgical accuracy

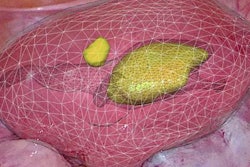

Taking VR a step further, AR not only can superimpose 3D virtual models of organs directly onto a patient but also enables clinicians to manipulate the images as they see fit, according to the authors. Furthermore, advanced AR technology allows for the possibility of hiding or highlighting different parts of the anatomy using a transparency function.

The AR models facilitate virtual surgical exploration, promoting a noninvasive and more precise way to plan and simulate surgical or ablative procedures, they noted. Specifically for liver surgery, AR offers clinicians a way to determine liver volume, plan resection planes along liver segments, locate portal pedicles, and analyze tumor margins.

Above all, the surgeons in the clinical studies examined sought to use AR to improve their operative experience for a variety of liver procedures, including the removal of colorectal cancer liver metastases, cholangiocarcinoma, and hepatoblastoma. All of the surgical teams reported increased accuracy in locating and resecting tumors with AR navigation, compared with more standard methods of image guidance.

A major barrier to universally incorporating AR into liver surgery is the variability involved in registering AR models to patient anatomy during surgery, Pessaux and colleagues noted. To that end, several different groups have begun experimenting with intraoperative ultrasound, cone-beam CT, and near-infrared fluorescence technologies for semiautomated AR registration.

One of the most recent trends in VR and AR research has been to integrate complementary intraoperative imaging modalities, such as combining intraoperative CT with optical tracking cameras or using a 4D ultrasound probe that fuses real-time ultrasonography with CT and MRI scans.

"The goal of achieving fully automated, robust, reproducible, and rapidly updated soft tissue AR registration is the next step towards the more widespread clinical application for a safer and more precise surgery," the authors wrote.