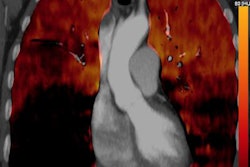

French researchers found that a set of clinical criteria was just as accurate as a protocol that included CT pulmonary angiography for ruling out pulmonary embolism (PE) in the emergency department, according to an article published in the February 13 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The investigators tested their pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) at the bedside of low-risk patients in the emergency department of 14 different medical centers. They compared its ability to exclude PE with results from the standard of care, which included D-dimer blood tests and imaging exams such as CT.

There was no statistically significant difference between PERC and the standard of care for detecting PE events in the nearly 2,000 patients during the follow-up period -- meaning that referrals of low-risk patients to imaging could be avoided (JAMA, February 13, 2018, Vol. 319:6, pp. 559-566).

"In the PERC group, there were fewer initial PEs diagnosed than in the usual care group, with little difference between the two groups in clinically significant thromboembolic events at three months," wrote first author Dr. Yonathan Freund, PhD, from Hôpital Universitaire Pitié-Salpêtrière in Paris, and colleagues. "These findings support the safety of PERC for very low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department."

Evolving diagnostic strategy

The way physicians diagnose PE has undergone considerable revision in recent years due, in part, to advances in imaging technology. Above all, the role of imaging modalities has been shifting.

"There are growing concerns on the potential overuse of diagnostic tests (especially CT pulmonary angiography) and possible overdiagnosis of PE," the authors wrote.

In the U.S., the current practice for identifying PE generally follows guidelines from the American College of Physicians (ACP), which recommends first using clinical prediction rules to determine risk, followed by D-dimer testing for patients who do not meet all of the criteria. Imaging exams such as CT pulmonary angiography should only enter the picture in cases of high pretest probability of PE, according to the college's recommendations.

As an alternative set of clinical criteria, PERC was designed to help reduce unnecessary testing and imaging for patients who have a low risk of PE. Several studies, including those conducted by Raja et al and Fesmire et al, found a false-negative rate of less than 2% when PERC was applied in U.S. emergency departments.

Yet two separate studies out of Europe by Righini et al and Hugli et al prompted controversy after reporting false-negative rates for PERC well exceeding the accepted minimum of 5% -- suggesting that PERC does not safely rule out PE for European patients, according to an accompanying editorial by Dr. Jeffrey Kline from Indiana University.

"More broadly, however, the two reports collectively raised concern that implementation of PERC could fail in Europe and other regions with higher disease prevalence than the United States," he wrote. "This concern was driven by the intercontinental difference in the baseline prevalence rates of PE among patients tested for PE."

The PROPER trial

In response to these conflicting claims, Freund and colleagues conducted the PERC Rule to Exclude Pulmonary Embolism in the Emergency Department (PROPER) trial, in which they compared PERC and the standard of care -- i.e., D-dimer testing and CT pulmonary angiography -- for ruling out PE.

From August 2015 to September 2016, the investigators performed PE diagnostic workups on 1,749 patients who had a low risk of PE and presented to 14 emergency departments in France. Patients in the standard care group underwent D-dimer testing after risk classification, followed by a CT pulmonary angiography exam for patients who were D-dimer positive. Those in the PERC group underwent the same process, unless a patient had a PERC score of 0, in which case the clinicians ruled out PE without subsequent testing.

After observing the patients for three months, the researchers found no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of symptomatic pulmonary thromboembolic events for patients assessed with the standard of care versus the PERC method. Nor was there a significant difference in the diagnostic yield of the CT pulmonary angiography exams for PE between the two groups, at11% for both.

| Standard care vs. PERC for workup of pulmonary embolism | |||

| Patient outcome | Standard care | PERC | p-value |

| Symptomatic pulmonary embolism within 3 months | 0% | 0.1% | -- |

| CT pulmonary angiography exam | 23% | 14% | < 0.001 |

| Median length of stay | 5 hours, 12 minutes | 4 hours, 34 minutes | < 0.001 |

| Hospital inpatient admission | 15% | 12% | 0.03 |

| Hospital readmission | 7% | 4% | 0.03 |

The PERC method led to a 1.3% absolute -- or a 48% relative -- lower initial diagnosis of PE, compared with the standard of care, which coincided with decreases in the amount of time patients spent in the emergency department (nearly 40 fewer minutes), their hospital admission rate (3% less), and how likely they were to undergo a CT pulmonary angiography exam (9% less often).

Minimizing unnecessary tests

"The PROPER trial shows that cost-free and immediately available data safely excluded PE in low-risk patients treated in French emergency departments and was associated with an 8% decrease in unnecessary CT scanning and a median 40-minute decrease in length of stay," Kline said.

With only about 5% of CT pulmonary angiography exams in U.S. emergency departments indicating PE, a reduction in these studies in both Europe and the U.S. would mean less radiation exposure, less potential for kidney injury from invasive imaging, and fewer costs, he said.

The notably lower diagnosis rate of PE in the PERC group compared with rates in previous research alludes to a key limitation of the study -- the uncertainty of whether or not incorporating PERC incorrectly ruled out some cases of PE, and the long-term ramifications of these potentially missed diagnoses.

Did the PERC method fail to catch several instances of mild PE, or did fewer patients actually have the disease? And if PERC did indeed overlook some PE, does the comparable prevalence of PE between the PERC and standard-care groups at three months suggest that isolated subsegmental PE might not warrant anticoagulation treatment?

Though the findings indicate that PERC may be inferior at capturing small subsegmental PE, this low-risk event may represent a tolerable risk to patient safety, the authors wrote.

Further work by the researchers will aim to address these questions, as well as explore the possibility of applying PERC for younger patients and quantify the potential cost benefits.

"Future research could evaluate the economic benefit of implementing PERC in routine practice," they wrote. "Furthermore, the safety and benefit of the modified PERC rule for patients younger than 35 years should be evaluated and compared to the initial PERC rule."