Dr. Walter Heindel, professor and director at the Clinical Radiology Institute, University of Münster, helped to pioneer Germany's mammographic screening program. In 2005, his team was among the first to offer routine early detection of breast cancer. In this interview, he outlines the risks, opportunities, and future of the national program, and shares his own strongly held views on why women should participate.

German Radiological Society (DRG): The state of North Rhine-Westphalia has had a mammography screening program for over 10 years. To what extent has it achieved its main objective of reducing breast cancer deaths?

Dr. Walter Heindel.

Dr. Walter Heindel.Heindel: For epidemiological reasons, we won't know the actual outcome until 2020, but we're increasingly convinced there will be an effect. All the parameters we've measured so far show that the German early detection program complies with European guidelines on breast cancer diagnosis. For example, the screening is identifying cancer at an increasingly early stage. More importantly, our team carried out a new study this year showing the number of large, advanced, and metastasized carcinomas -- the most dangerous kinds for affected women -- decreases on subsequent screening.

So women with cancer have a better prognosis as a result of being screened?

Precisely. We've shown statistically that women who are repeatedly screened and who get cancer have a significantly better recovery rate than those who aren't. Of course, the program does have its critics, some of them oncologists who say we don't need all this and that new forms of chemotherapy and immunotherapy are increasingly effective these days. The effect we've shown begins earlier, at the diagnostic stage. Proving a decrease in advanced-stage tumors among participants is the last step before you start looking at mortality. But for methodological and pathology reasons, epidemiologists won't be able to do that until 2020.

How important is it for women to have regular screening?

It's vital. All the studies show the program is particularly beneficial if you keep calling women back for screening. There are some women who say they'll come back in four years, but not before that. They don't benefit as much as women who attend regularly.

What would you say are the specific advantages of screening for women?

We see three main advantages. One, we're increasingly often able to save the breast surgically because the tumor is still small. Two, the axillary lymph nodes are increasingly often tumor-free, with no metastasis, which is very important for the patient's prognosis. And three, they need fewer doses of chemotherapy because the tumor can be treated using less aggressive therapies.

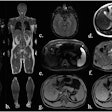

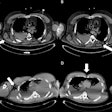

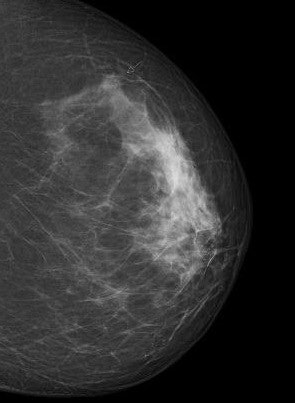

Digital screening mammogram of a 50-year-old woman taking part in the program for the first time. An invasive carcinoma was found, with precancerous microcalcifications nearby. The tumor was at an early stage. All images courtesy of Dr. Walter Heindel and the DRG.

Digital screening mammogram of a 50-year-old woman taking part in the program for the first time. An invasive carcinoma was found, with precancerous microcalcifications nearby. The tumor was at an early stage. All images courtesy of Dr. Walter Heindel and the DRG.But one of the disadvantages is the possibility of a false-positive diagnosis.

We need to start by explaining exactly what screening is: It's an initial search method that distinguishes between "normal" and "abnormal." An "abnormal" finding currently means the diagnosis has to be confirmed using additional methods. A screening mammogram doesn't clearly tell us whether the abnormality in the image is malignant, or why it's abnormal. If we eventually find it's benign, or there hasn't actually been a tissue change, we call it a false positive.

Statistically, for every 200 screenings we carry out, we find about five abnormalities. This is obviously worrying for the women involved, because they have to come back for a follow-up examination, though we normally tell them in most cases the examination is just to rule out a particular diagnosis. In fact, four out of every five women we examine don't present any cause for concern. On average, we have to take tissue samples from two of the women, and one out of the five does have a carcinoma. That's roughly what happens after repeated screening. In my opinion, this criticism is a bit over the top.

Another problem is overdiagnosis.

What this means is you find a tumor or a precancerous condition, but the clinical symptoms wouldn't have been found without targeted diagnostics, and the woman wouldn't have died. That's overdiagnosis. But even if a woman is diagnosed with an aggressive cancer and is killed by a car accident or heart attack a month later, then that's overdiagnosis by definition.

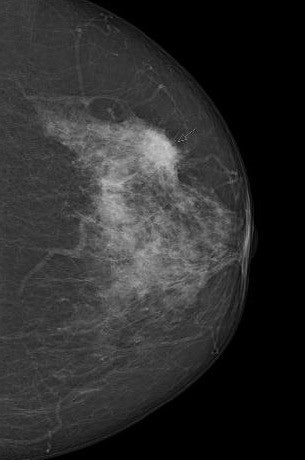

Digital screening mammogram of a 50-year-old woman taking part in the program for the first time. The patient had not noticed the relatively superficial tumor, which was at an advanced stage.

Digital screening mammogram of a 50-year-old woman taking part in the program for the first time. The patient had not noticed the relatively superficial tumor, which was at an advanced stage.You can only determine with hindsight whether an individual case is an overdiagnosis. We're not psychic, so this is a difficult debate. Overdiagnosis happens all the time in medicine. If a polyp, which is a precancerous condition, is removed during a preventive colon cancer examination, this can result in overdiagnosis and overtreatment. No one can say for sure whether the polyp would really have developed into a symptomatic carcinoma. You can only measure the absolute number of overdiagnoses with a 10-year observation interval after an early screening program compared with a control group. Realistically, we estimate that about 6% to 10% of all tumor findings are overdiagnoses.

Is it possible to miss a tumor during screening?

Any examination method can overlook a tumor, and this is something else you have to be open about. It's called a false-negative finding, and we can minimize it by using modern, proven mammography techniques and by providing special training for all screening teams, including radiologists and doctors. This is also why we use dual diagnosis: Each mammogram must be separately analyzed by at least two doctors. Two pairs of eyes are better than one, and this method gives at least a 15% increase in tumor detection rates than with one doctor.

How often do false negatives happen?

We don't have an exact figure for Germany yet, but we're working on it. North Rhine-Westphalia is the biggest state, and cancer epidemiology records there show an early-detection initiative using a two-year mammography screening program identifies 78% of all breast carcinomas. The other 22% occur after this, in the interval between two screenings, most often because they occur after the screening and are not detected. These true interval carcinomas, as we call them, are unavoidable and often very aggressive and fast growing. Only a small proportion of interval carcinomas -- around 20%, according to studies in other European countries -- occur because diagnosing physicians fail to recognize or misidentify an obvious abnormality, or because of a technical error, for example if the tumor is not visible because the image does not cover the whole breast.

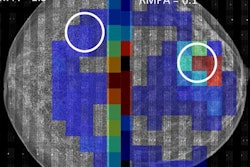

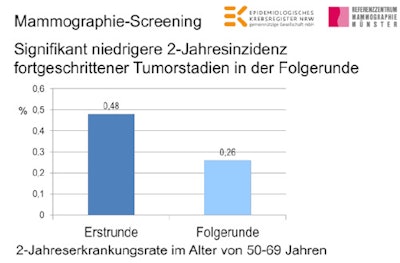

For the first time in Germany, it has been shown that screening mammography reduces the two-year incidence rate of advanced-stage tumors. Mammographie-Screening = Screening mammography. Signifikant niedrige 2-Jahresinzidenz fortgeschrittener Tumorstadien in der Folgerunde = Significantly lower two-year advanced-stage tumor incidence on follow-up screening. Erstrunde = First screening. Folgerunde = Follow-up screening. 2-Jahreserkrankungsrate im Alter von 50-69 Jahren = Two-year incidence rate in women ages 50 to 69.

For the first time in Germany, it has been shown that screening mammography reduces the two-year incidence rate of advanced-stage tumors. Mammographie-Screening = Screening mammography. Signifikant niedrige 2-Jahresinzidenz fortgeschrittener Tumorstadien in der Folgerunde = Significantly lower two-year advanced-stage tumor incidence on follow-up screening. Erstrunde = First screening. Folgerunde = Follow-up screening. 2-Jahreserkrankungsrate im Alter von 50-69 Jahren = Two-year incidence rate in women ages 50 to 69.Some experts believe MRI is a better diagnostic tool than mammography.

Yes, there are some who say we should use MRI for screening, partly because it doesn't use x-rays. But it's more complicated and expensive, you need a contrast medium, and you can get more false positives and overdiagnoses. I think MRI is a very good examination, but its value as an epidemiological screening technique needs to be scientifically proven.

Of course, it's a standard diagnostic procedure for high-risk women.

Rightly so, in my opinion. And indeed for women like Angelina Jolie who have an above-average breast-cancer risk, in some cases up to 70% or 80%, caused by an inherited genetic defect. In Germany, they can get early intensive screening, which uses MRI, and, depending on their age, includes ultrasound and a mammogram. The next step for us is to show that the early intensive screening program reduces mortality.

And mammograms have their limitations when it comes to particularly dense tissue?

Yes, for women on the program who are ages 50 and older and have very dense type 4 breast tissue, although they really are the exception. Digital mammography, which is now standard in screening, penetrates dense tissue much better than analog x-rays 10 years ago.

We've just carried out a study in Münster of the density at which mammographic sensitivity declines. We found that contrary to what has been written elsewhere, sensitivity starts declining only with extremely dense type 4 tissue. We found no significant difference in sensitivity for women with a density of 1 to 3. Our study found the two-year interval screening mammogram program was significantly below average in only five percent of women. We need to consider giving them additional screening.

Which techniques do you think should be used in addition to mammography?

Ultrasound, tomosynthesis, and possibly MR mammography. We need to discuss which procedures work, and which give too many false positives and inconclusive results that may need re-evaluation and don't influence disease outcomes.

So there's no single way of carrying out a radiological diagnosis?

Early detection is always a balancing act between risks and benefits, so you need to continually evaluate the facts. You can quantify the pros and cons of the examination procedure, particularly in a transparent, quality-assured system like screening mammography. Recording and evaluating the outcomes is a long, drawn out process, but screening makes it possible for the first time.

How do you expect the screening mammography program to develop?

Breast screening will continue to stimulate the development of new diagnostic imaging technology. The next step is already taking place with the development of digital mammography into tomosynthesis, which examines the breast using layered imaging. In an aging society, we need to consider offering screening mammograms past the age of 69, for example until 75.

A lot of women can't decide whether to join the program. What would you advise?

This is how I see it personally: Some cancers can be detected and treated early, such as breast and colon cancers, and others can't, such as pancreatic cancer. But we can all be proactive in tackling other diseases, as they're often very treatable. And as they're more common, women should welcome early diagnosis. Early detection has nothing to do with disease: It's a part of being alive and looking after yourself. That's the idea behind screening. We should all ensure we're well informed, and then make personal decisions.

Editor's note: This is an edited version of a translation of an article published in German online by the German Radiological Society (DRG, Deutsche Röntgengesellschaft). Translation by Syntacta Translation & Interpreting. To read the original article, published to coincide with the International Day of Radiology on 8 November, click here.