There is indeed a reduction in breast cancer mortality as a result of mammography screening in women who start getting exams at age 40 -- at least in the first 10 years of follow-up, according to a new study in Lancet Oncology that followed women for 17 years.

The study reports on the U.K. Age trial, which was designed specifically to examine the effect of mammography screening starting at age 40. The randomized controlled trial looked at breast cancer mortality and incidence at a median of 17.7 years of follow-up, an increase of seven years from when follow-up of the Age trial was last published.

The research team, which included mammography screening advocate Dr. Stephen Duffy from the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine in London, and cancer epidemiologist Robert Smith, PhD, from the American Cancer Society, noted a significant reduction in breast cancer mortality in the intervention group compared with the control group in the first 10 years after diagnosis (Lancet Oncol, 21 July 2015).

"The long-term results from the U.K. Age trial presented here show a significant reduction in the risk of breast cancer mortality in the intervention group [i.e., women who started screening at 40] compared with the control group in the first 10 years, followed by no difference between the groups thereafter, when analysis was restricted to breast cancers diagnosed during the intervention phase," wrote the study authors, led by Sue Moss, PhD, also from the Wolfson Institute.

The absolute effect of breast screening in this age group is difficult to assess when deaths from cancers diagnosed after the first 10 years of screening are included, because both groups receive the same care at age 50, and underlying incidence and mortality are substantially increased in women older than 50, they added.

Controversy around age 40

Many studies have called mammography into question, including one published earlier this month by Autier et al that stated that screening mammography's benefits have been overestimated due to unconventional statistical methods. Setting aside the argument whether screening mammography is effective or not, there is also much debate around what age to start screening.

A recent review by the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded there was limited evidence for the efficacy of screening women ages 40 to 49. However, it has been argued that evidence from randomized controlled trials may not be the best vehicle for determining the effectiveness of mammography in women in their 40s compared with that in older women; indeed, evidence from screening programs supports a more optimistic view of the benefits of mammography in women ages 40 to 49, Moss and colleagues wrote.

In 2009 in the U.S., the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) revised its 2002 recommendations that women in their 40s should undergo mammography screening every one to two years, and now recommends against routine screening mammography for women in this age group based mainly on what it judged to be an uncertain balance of benefits and harms. The group declined to change that recommendation in a recent policy review.

The U.K. Age trial

Starting in 1991, the Age trial followed women ages 39 to 41 from 23 U.K. National Health Service (NHS) Breast Screening Programme units who were randomly assigned to either an intervention group (nearly 54,000 women) that offered annual screening by mammography up to and including the calendar year of their 48th birthday, or to a control group (nearly 107,000 women) receiving usual medical care. "Usual medical care" in this case means invited for screening at age 50 and every three years thereafter.

The researchers compared breast cancer incidence and mortality by number of years of follow-up since the study began. Analyses included all women randomly assigned who could be traced with the NHS Central Register and who had not died or emigrated before entry. The primary outcome measures were mortality from breast cancer and breast cancer incidence, including in-situ, invasive, and total incidence.

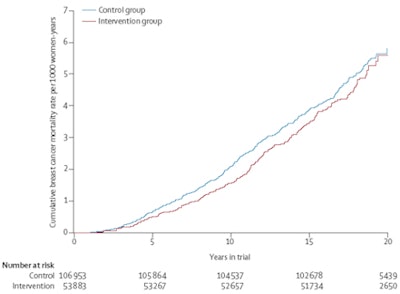

The researchers noted a statistically significant reduction in breast cancer mortality in the group that started screening at 40 compared with the control group in the first 10 years after diagnosis, with a rate ratio (RR) of 0.75, but not thereafter (RR 1.02). After 17 years of follow-up, the study found an RR of 0.88 for breast cancer mortality from tumors diagnosed in the intervention phase.

The overall breast cancer incidence during 17-year follow-up was similar between women who started screening at age 40 and the control group (RR 0.98).

"The reported difference in breast cancer mortality peaked when the analysis was restricted to breast cancers diagnosed up to seven years of follow-up, despite the fact that at this point in time, there was an excess of breast cancer incidence in the intervention group [women who started screening at age 40], which would tend to introduce a bias against screening as some of this excess will be due to the effect of lead time," the authors wrote.

In other words, the analysis includes deaths from cancers in the women who started screening at 40 whose equivalent in the control group are excluded because they will be diagnosed after the seven-year period. After year 7 or 8, the two groups have essentially the same screening regimen.

Nelson-Aalen estimate of cumulative breast cancer mortality (all dates of diagnosis). Copyright Lancet Oncology.

Nelson-Aalen estimate of cumulative breast cancer mortality (all dates of diagnosis). Copyright Lancet Oncology.The authors also noted that the NHS Breast Screening Programme now routinely uses two-view mammography at all screens, which has resulted in improved detection, lower recall, and a lower incidence of interval cancers, something Dr. Daniel Kopans from Harvard Medical School mentions in an accompanying editorial (Lancet, 20 July 2015).

"These results are actually remarkable in view of some major limitations of the trial. For instance, despite the fact that radiation risk to the breast for women aged 40 years and older is very low, concerns about radiation exposure lead the U.K. Age trial investigators to use a single view (mediolateral oblique) for incidence screening instead of the two views used in the USA," Kopans wrote. "In the U.K., investigators have shown that using only the projection meant that the screening probably missed 25% of early breast cancers."

Kopans contends that no scientific evidence exists for a screening threshold at the age of 50. His sentiments are echoed by screening advocates Dr. László Tabár from Falun University Hospital in Sweden and Dr. Peter Dean from the University of Turku in Finland.

"We congratulate the authors of the Lancet mammography screening article proving the beneficial effect of early detection on women in their 40s. Although there is no biologic reason why early detection of breast cancer should not work in women at any age, it has taken a long time to prove this for the younger women in a specifically designed scientific trial," Tabár and Dean wrote in an email to AuntMinnieEurope.com.

They also add to make screening even more effective, the one-year interscreening interval and the use of a multimodality approach -- digital mammography combined with automated breast ultrasound -- should be used for women of any age with dense breast tissue.

"The excellent results presented in this article can still be improved by also addressing the problems associated with dense breast tissue in addition to the more rapid tumor growth rate in younger women," they wrote.

What about overdiagnosis?

The U.K. Age trial researchers also addressed the subject of overdiagnosis, or the detection of abnormalities that might never pose a threat to a women in her lifetime.

Because the women who started screening at 40 showed no excess incidence after entry into the breast screening program, it suggests that overdiagnosis is "at worst a very minor occurrence," according to the authors. During the intervention phase when only the women who started screening at 40 were examined, the difference in incidence was small, and even a potential short lead time would rule out substantial overdiagnosis, they added.

"Overall, these results support an early reduction in mortality from breast cancer with annual mammography screening in women aged 40-49 years," they concluded. "Synthesis of results from all the trials and further data from modern service screening might clarify long-term effects."