The increasing use of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin markers in European hospitals is changing the practice of chest pain management in significant ways -- eliminating the need for coronary CT angiography (CCTA) in some cases, and increasing it in others, according to research presented at last week's International Symposium on Multidetector-row CT.

While CT is excellent at ruling out acute coronary syndrome (ACS), today's high-sensitivity troponins also allow for conclusive rule out of ACS -- sometimes before the CT scan can even be performed, said Dr. Koen Nieman, PhD, from Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. At the same time, the positive predictive value of the markers is lower than that of CCTA, so "for patients in the gray area, CT has a role in those patients in whom ACS has been ruled out," he noted.

Ruling out ACS via negative troponin results still means that CCTA is needed to rule out coronary artery disease, but less urgently, meaning it can be performed carefully during the day.

It was not so long ago that chest pain patients with initial negative markers combined with normal ECG readings used to have to stay in the hospital for at least 12 hours for observation. CCTA has helped eliminate those lengthy stays, and the costs associated with them, by allowing the safe discharge of patients without significant stenosis, Nieman said.

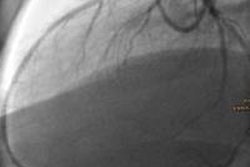

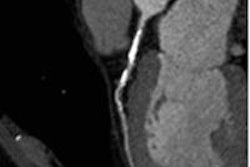

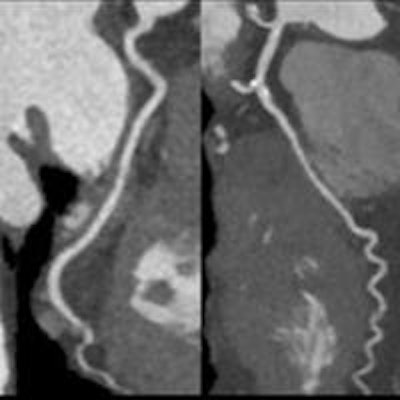

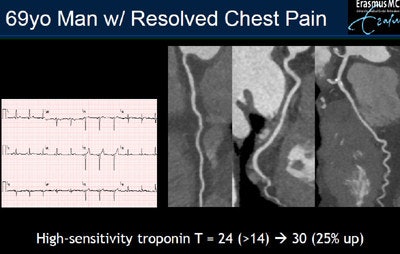

In a 69-year-old man with resolved chest pain, initial high-sensitivity troponins results reached 24 ng/L, a little over the 14 ng/L threshold. A second set of markers acquired several hours later came in at 30 ng/L, a 25% increase, prompting a referral to coronary CT angiography, which showed no stenosis. Based on CT, the patient was safely sent home without additional tests. Images courtesy of Dr. Koen Nieman, PhD.

In a 69-year-old man with resolved chest pain, initial high-sensitivity troponins results reached 24 ng/L, a little over the 14 ng/L threshold. A second set of markers acquired several hours later came in at 30 ng/L, a 25% increase, prompting a referral to coronary CT angiography, which showed no stenosis. Based on CT, the patient was safely sent home without additional tests. Images courtesy of Dr. Koen Nieman, PhD.CT is excellent at excluding coronary artery disease based on the absence of significant stenosis, as evidenced in the ROMICAT II and other trials, but it's not always definitive. Relying on CT alone, "you will still miss a few patients that have no obvious stenosis but develop [non-ST-segment-elevated myocardial infarction] non-STEMI," he said.

"So if you exclude coronary disease based on plaque presence you will reach 100% sensitivity, but you will forfeit specificity," Nieman said. "What we usually do is exclude patients. We rule out ACS. If they have completely normal coronaries they are discharged immediately; if they have plaque second markers, we will let the patient go if the symptoms have resolved over that time."

In the case of a "frequent flyer" -- i.e., a patient who presented routinely to the emergency department with chest pain -- CT helped break the cycle of repeat visits, according to Nieman. The last time he turned up, the primary physician was off duty and the doctor replacing him saw that it was the patient's fourth visit to the emergency room. Because the patient's blood markers had been consistently negative, his testing has always been noninvasive. But during this episode, the emergency department team ordered CCTA. "We found completely normal coronary arteries, which is very reassuring and the patient could be sent home this time and probably the next time."

Several randomized trials have shown that most measures improved with the use of CCTA, from logistics of patient management to the economics of the chest pain episode.

In ROMICAT II, which screened chest pain patients at low to intermediate risk of ACS, for example, the median length of stay for chest pain patients improved from 31 to 23 hours with the use of CCTA. The emergency department discharge rate rose from 12% to 47% after the CT scan, he continued. ROMICAT II didn't show improved economics with the use of CT, but the ACRIN trial did (along with a reduction in the mean length of stay from 25 hours to 18 hours), and that trial also demonstrated that sending CT-negative patients home led to an extremely low event rate.

"So there's very convincing evidence that CT could be of use particularly for logistic reasons, and that it's safe," he said. "But whether that's still true in the current time -- that's the question."

For now, a European question

High-sensitivity troponins are standard practice in the Netherlands and much of Europe, but "as I understand it, high-sensitivity troponins aren't much used in the U.S. yet," Nieman said. Their ability to recognize very low levels of troponins makes them more sensitive than standard assays, and most important, they are diagnostic much faster than standard assays, which reached 95% sensitivity after 12 hours and necessitated the patient's long hospital stay -- versus maximum sensitivity in three hours for high-sensitivity tropononins.

But with the high-sensitivity troponins, 95% sensitivity can be reached after three hours, which is much faster than before, and considerably changed the consequences for clinical practice, he explained.

Dr. Koen Nieman, PhD, from Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Dr. Koen Nieman, PhD, from Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.Another trial that looked at a somewhat older population found that most patients were positive when troponins were measured immediately on admission. Importantly, results from the second set of markers showed the first markers were diagnostic, thus the initial diagnosis of non-STEMI remained after the second test. But even though more than half of the patients had positive markers, the prevalence of non-STEMI was only 20%, "which means we also start to overestimate disease with these new markers," Nieman said. "So we gain sensitivity but we lose specificity."

The results are echoed in a new recommendation from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), which advises that in the setting of high-sensitivity troponins that are negative, the first set of normal markers is sufficient to rule out coronary artery disease if the patient's chest pain complaint has lasted more than six hours. On the other hand, if the patient's pain has lasted less than six hours, a second set of markers is required. If these results show no dramatic changes, the patient can be safely discharged and alternative diagnoses considered. If the second set of markers shows an increase, then the patient will be referred for invasive management, he said.

"Now this is not totally accepted, but I think what is most important is that CT can play a role, particularly in patients with low elevated markers," Nieman said. "Instead of sending them all to the cath lab, we realize now that most of them will not have an acute coronary syndrome that needs to be treated immediately."

Finally, ACS-negative or not, these patients still need CT to rule out coronary artery disease, but it would seem wiser to perform it on an outpatient basis and not in the middle of the night in the emergency department.

"We can do it in a much more controlled way by experienced technologists, perhaps combined with FFR [fractional flow reserve] or perfusion imaging, but do it during the day -- which will be safe after these negative markers," he concluded.