A negative PET scan immediately after three cycles of chemotherapy for early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma can identify patients with an excellent prognosis and avoid unnecessary additional radiation therapy, according to a U.K. study published on 23 April in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study found that after five years, patients with stage IA or stage IIA Hodgkin's lymphoma and a negative PET scan had had an overall survival rate without disease progression of 90.5% (NEJM, 23 April 2015, Vol. 372:17, pp. 1598-1607). And while more patients died in the group that didn't get radiation therapy, it's believed that they will suffer fewer radiation-related side effects down the road.

"PET is useful because it has a high negative predictive value," noted lead author Dr. John Radford, professor of medical oncology and honorary consultant at the University of Manchester and the Christie National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, in an email to AuntMinnieEurope.com. "If a PET scan is negative after treatment, the patient has a very good chance of not experiencing a relapse."

Data from the study comes from the U.K.'s RAPID trial, one of the first initiatives to test the role of response-adapted therapy using PET in lymphoma.

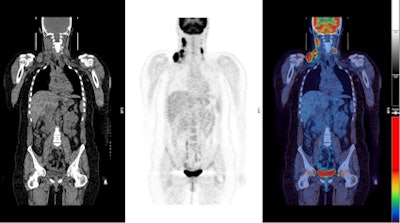

PET/CT images show a Hodgkin's lymphoma patient with a negative PET scan after chemotherapy. There is high uptake in lymph nodes on both sides of the neck prior to treatment (above), which resolved after chemotherapy (below). Physiological uptake is also seen in the heart and bladder. Images courtesy of Dr. Sally Barrington, reader in nuclear medicine, PET Imaging Centre at St Thomas' Hospital in London.

PET/CT images show a Hodgkin's lymphoma patient with a negative PET scan after chemotherapy. There is high uptake in lymph nodes on both sides of the neck prior to treatment (above), which resolved after chemotherapy (below). Physiological uptake is also seen in the heart and bladder. Images courtesy of Dr. Sally Barrington, reader in nuclear medicine, PET Imaging Centre at St Thomas' Hospital in London.Hodgkin's lymphoma occurrence

Estimates are that approximately 1,900 people are diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma in the U.K. annually; many of these cases are teenagers and young adults.

The current standard of care is for Hodgkin's lymphoma patients to receive chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy. The downside of radiotherapy includes eventual side effects, such as cardiovascular disease and other forms of cancers, even among patients who have been cured of Hodgkin's lymphoma.

While radiotherapy after initial chemotherapy marginally reduces the recurrence of Hodgkin's lymphoma in patients with an early form of the disease, researchers in this study stated that the benefits come at the risk of exposing all patients with negative PET findings to unnecessary radiation, even people whose disease is in remission.

"Defining optimal treatment in early stage Hodgkin's lymphoma is important so that we can maximize cure and minimize late toxicity for this group of patients," Radford added.

PET's prognosis

In this study, a total of 602 patients were enrolled in the RAPID trial at 94 centers in the U.K. between October 2003 and August 2010. The median age of the subjects was 34 years old, ranging from 16 to 75 years old. Among the participants were 321 men (53%) and 200 women (33%) with stage IA Hodgkin's lymphoma.

PET imaging was performed on full-ring PET or PET/CT scanners at centers within the U.K. National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) PET Research Network. PET images were negative among 426 patients (75%). Individuals who had positive PET results continued on to receive additional radiotherapy.

Radford and colleagues randomly divided 420 of the PET-negative patients into two groups, some who received radiotherapy and some who did not. After ruling out some patients whose care didn't follow the study protocol (such as by receiving radiation therapy despite being assigned to the no-treatment group), they were left with a total of 392 patients.

Among these patients, PET-negative patients who received radiation therapy had a three-year progression-free survival rate of 97.1%, while the PET-negative individuals who received no treatment had a survival rate of 90.8%.

The researchers acknowledged that it's understandable that there would be a higher rate of progression-free survival in the group that received radiation therapy, because PET's negative predictive value is less than 100%.

"This was judged to be acceptable, as long as the reduction in disease control was not excessive, because of the likely benefits in overall survival that would result from a lower incidence of second cancers and cardiovascular disease in association with exposing fewer patients to radiation," they wrote.

Based on the numbers, researchers concluded that patients with negative PET findings after three cycles of chemotherapy "have a very good prognosis either with or without consolidation radiotherapy," adding that the results "suggest that radiotherapy can be avoided for patients with negative PET findings."

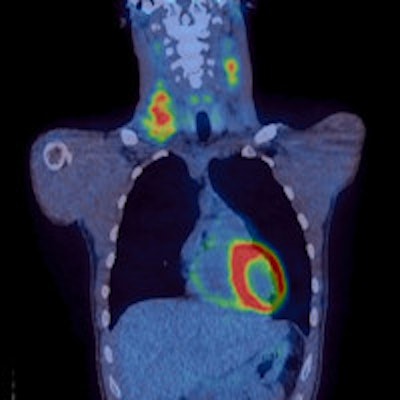

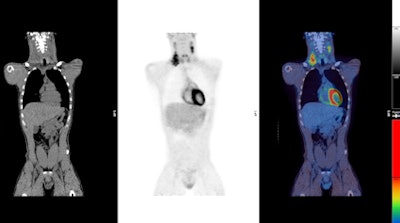

PET/CT images show a Hodgkin's lymphoma patient with inadequate response to treatment or "positive" PET scan after chemotherapy treatment. There was high uptake in lymph nodes on both sides of the neck prior to treatment (above) with persistent high uptake in the right neck after treatment; Deauville score 5 (below). The Deauville criteria is a five-point scoring system used to calculate uptake in PET images. A score of 5 would indicate the greatest amount of uptake. Physiological uptake is seen in the bladder.

PET/CT images show a Hodgkin's lymphoma patient with inadequate response to treatment or "positive" PET scan after chemotherapy treatment. There was high uptake in lymph nodes on both sides of the neck prior to treatment (above) with persistent high uptake in the right neck after treatment; Deauville score 5 (below). The Deauville criteria is a five-point scoring system used to calculate uptake in PET images. A score of 5 would indicate the greatest amount of uptake. Physiological uptake is seen in the bladder.Follow-up research

While these findings are very encouraging, Radford and colleagues recommend a longer follow-up study to determine whether the use of PET to determine a patient's condition will "lead to fewer second cancers, less cardiovascular disease, and improved overall survival, as compared with a strategy incorporating radiotherapy for all patients."

The group is continuing its research by evaluating semiobjective methods for reporting PET images and integrating tissue-based biomarkers with PET to improve the allocation of treatment to ensure that patients at greatest risk of recurrence receive the most treatment and those at lowest risk receive the least.

Radford, who is chair of the U.K. NCRI Lymphoma Clinical Studies Group, believes the results of this study "are very likely to influence practice worldwide." He has been invited to speak on this topic at the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma meeting in Lugano, Switzerland, in June.