How long will my player be out of action? That's the burning question posed by most managers in today's ultracompetitive, high-pressure environment of top-flight football, and often the radiologist is the only person who can provide the decisive answer.

Dr. Justin Lee, a consultant radiologist at London's Chelsea and Westminster Hospital who specializes in musculoskeletal imaging, thinks it's important never to underestimate an elite athlete's desire to win and to return to action. He thinks this point is exemplified by their response to this question: If I were to offer you a drug that would guarantee you an Olympic gold medal without being found out, but you would die in five years time, would you take it? Typically in the general population, 2% would say "yes," but the figure for athletes is consistently more than 50%.

"Nearly everybody in elite sports gets an MRI, at least in the U.K., and MRI forms the mainstay of imaging," he told delegates at the 2013 U.K. Radiological Conference during a talk on muscle injury in footballers. "But you may want to do an ultrasound scan for every grade I injury just to make sure there is no fiber separation and, if so, to find out how big it is."

In football, muscle strains are very common, accounting for between 37% and 42% of absences among players. Architectural distortion detected by MRI or ultrasound means a prolonged recovery time, as does free tendon involvement. The next most frequent cause of absence is ligament injury (18% to 20%), followed by muscle contusion and tendinitis/paratendinitis (3% to 5% each).

In suspected cases of muscle injury, Lee stressed that these main questions must be addressed: Is there a macroscopic lesion? Which muscle is involved, and where is the injury? Is there a hematoma? And is there a scar? Also, tissue healing must be assessed. Footballers' legs often have multiple tears and multiple scars, according to Lee, who has worked for a range of sports professionals in the U.K., including Premier League and Championship football clubs, Premiership rugby clubs, as well as the Olympic Team GB. He has also worked for the NFL International Series UK and the British and Irish Lions rugby squad.

Along with Lee and his Chelsea and Westminster colleague Dr. Jerry Healy, Dr. Jan Ekstrand, an orthopedic surgeon who runs the medical division of the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), organized a study in the 2007-2008 Champions League season that looked at muscle injuries to thighs. Included in the study were Chelsea, Arsenal, Inter Milan, PSV Eindhoven, FC Shakhtar Donetsk (Ukraine), and FC Porto. A total of 303 injuries were recorded by the 18 participating teams, and hamstrings were affected in 184 cases (61%) and the quadriceps in 119 players (39%).

Overall, MRI accounted for the majority of examinations in seven clubs. Mostly ultrasound, along with some MRI, was performed at eight clubs, while another three clubs relied largely on clinical examinations, according to Lee, who noted that the study is now being extended and updated. "Large numbers are required for us to achieve adequate statistical significance," he commented.

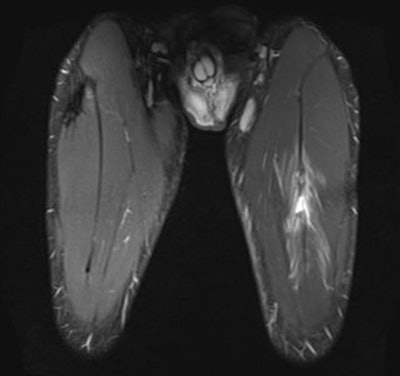

A 24-year-old male professional football player who presented with sudden onset of pain following striking of the ball. Above: Coronal STIR MRI demonstrates focal defect within the left rectus femoris central muscle at

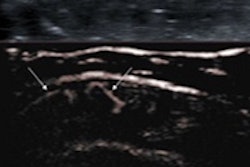

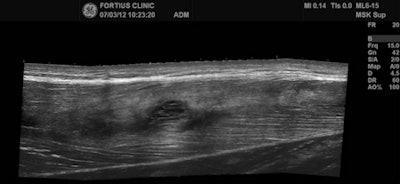

A 24-year-old male professional football player who presented with sudden onset of pain following striking of the ball. Above: Coronal STIR MRI demonstrates focal defect within the left rectus femoris central muscle at the musculotendinous junction. Note the feathery edema pattern within the muscle radiating from the primary injury site. Below: Extended field-of-view ultrasound demonstrates loculated hematoma at the musculotendinous junction with surrounding increased reflectivity within the rectus femoris muscle. All images courtesy of Dr. Justin Lee, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital.

MRI is the modality of choice in many football injuries (see figure). For grade I muscle injuries, it can detect abnormalities to the biceps femoris and myotendinous junction. In acute cases, there is a slight increase in signal on T1-weighted images, and a "feather-like" increased signal can be seen on T2/short tau inversion recovery (STIR), but there is no architectural distortion.

More and more football clubs have invested in their own ultrasound machines and are getting increasingly competent at following up these cases themselves. An ultrasound scan is often normal in these patients, however. Hyperechoic infiltration has been identified in14 out of 23 athletes with grade I muscle strain, and a band of perifascial fluid is greater in 3 out of 7 cases after injury.

Ultrasound is useful for effective differentiation between grade I and grade II muscle injuries, he added. For grade II injuries, MRI appearances include the focal area of muscle disruption, focal intramuscular mass/hematoma, and focal intramuscular fluid collection. Among the ultrasound appearances are discontinuous echogenic perimysial striae, "mass-like" disruption of fibers, irregular intramuscular fluid collection, hyperechoic halo, surrounding increased vascularity. Dynamic scans can enhance the size and contrast.

In grade III muscle injuries, it is important to look out for apophyseal avulsion, particularly in athletes between 15 and 25 years of age, and myotendinous avulsion and myotendinous tear also may occur. For complete myotendinous avulsion, MRI is far superior to ultrasound, and the mixed echogenicity of large hematomas makes it difficult to detect tendon ends, Lee emphasized.

To investigate scarring, he recommends use of T1 imaging rather than proton density imaging in muscle because it's vital to assess the amount of fat infiltration around the scar. "Once you've got a scar, there's a five times greater risk of injury over someone who doesn't have a scar," he said.

On ultrasound, it is possible to have a mass-like disruption of the fibers. A halo around the central tendon may be visible, with the increased vascularity, and sometimes contraction of the muscle can provide a more accurate assessment of the size of the tear, Lee said. If no macroscopic lesion involved, the player can make a rapid return to play. Ultrasound is the main tool to assess tissue healing.

If the MRI examination is normal, the player will be absent for less than a week, but the rehabilitation time tends to double if a free tendon is involved. For a grade I injury, the absence is around two weeks, compared with three weeks for a grade II injury and more than eight weeks for a grade III injury, he concluded.

Additional information

Ekstrand J, Healy JC, Waldén M, Lee JC, English B, Hägglund M. Hamstring muscle injuries in professional football: The correlation of MRI findings with return to play. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(2):112-117.