An international group of researchers has issued a fresh, but controversial, warning about the high cost and possible dangers of harming healthy people through earlier detection and ever wider definition of disease. This follows news that a scientific conference, Preventing Overdiagnosis, will take place in September 2013, suggesting the issue is moving up the global healthcare agenda.

"A burgeoning scientific literature is fueling public concerns that too many people are being overdosed, overtreated, and overdiagnosed. Screening programs are detecting early cancers that will never cause symptoms or death, sensitive diagnostic technologies identify 'abnormalities' so tiny they will remain benign, while widening disease definitions mean people at ever lower risks receive permanent medical labels and lifelong treatments that will fail to benefit many of them," noted lead author Ray Moynihan, senior research fellow at Bond University in Robina, Queensland, Australia, in an article due to go live today on the British Medical Journal's website, bmj.com (BMJ, May 2012, Vol. 344, p. e3502).

Diagnostic scanning of the abdomen, pelvis, chest, head, and neck can reveal "incidental findings" in up to 40% of individuals being tested for other reasons, he argued. Most of these "incidentalomas" are benign, and a very small number of people will benefit from early detection of an incidental malignant tumor, while others will suffer the anxiety and adverse effects of further investigation and treatment of an "abnormality" that would never have harmed them, according to Moynihan.

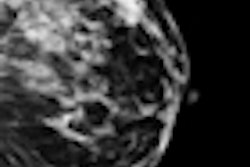

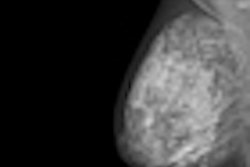

3D CT scans supply incredibly detailed information about the abdomen, but are such investigations always clinically valuable? Image courtesy of Hitachi.

3D CT scans supply incredibly detailed information about the abdomen, but are such investigations always clinically valuable? Image courtesy of Hitachi.Another area singled out for criticism is pulmonary embolism. CT pulmonary angiography can detect ever smaller clots, and there is uncertainty about whether treatment is always necessary, the authors wrote. The widespread introduction of CT pulmonary angiography has contributed to a substantial increase in incidence, much of which consists of clinically unimportant cases that would not have been fatal even if left undiagnosed and untreated, they stated.

Arguably the strongest evidence of overdiagnosis comes from studies of screening detected breast cancers, though estimates of its extent are wide-ranging, continued the authors. A 2007 review in Lancet Oncology found the proportion of overdiagnosis of invasive breast cancer among women in their 50s ranged from 1.7% to 54%. An Australian study estimated the rate was at least 30%, while a Norwegian study put the figure at 15% to 25%. A 2009 review in the BMJ found up to one-third of all screening detected cancers may be overdiagnosed, and it is currently impossible to discriminate between cancers that will harm and those that will not, they wrote.

The cumulative burden from overdiagnosis poses a significant threat to human health, and the downsides include the negative effects of unnecessary labeling, the harms of unneeded tests and therapies, and the opportunity cost of wasted resources that could be better used to treat or prevent genuine illness, continued Moynihan, who is getting a doctorate in the subject. His co-authors for this article were Dr. Jenny Doust, professor of clinical epidemiology at the Centre for Research in Evidence-Based Practice at Bond University, and Dr. David Henry, CEO of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Toronto.

"The challenge is to articulate the nature and extent of the problem more widely, identify the patterns and drivers, and develop a suite of responses from the clinical to the cultural," they wrote. "At the clinical level, a key aim is to better discriminate between benign 'abnormalities' and those that will go on to cause harm. In terms of education and raising awareness among both the public and professionals, more honest information is needed about the risk of overdiagnosis, particularly related to screening."

A key contributor is advances in technology, especially screening-detected overdiagnosis in people without symptoms, overdiagnosis resulting from use of increasingly sensitive tests in those with symptoms, overdiagnosis made incidentally, and overdiagnosis resulting from excessively widened disease definitions, they noted. A more rigorous classification of the different forms of overdiagnosis will be a focus of discussion at the 2013 Preventing Overdiagnosis congress, which will take place in the U.S. on 10-12 September and will be hosted by the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, along with the BMJ, Consumer Reports, and Bond University.

"Changes in diagnostic technologies or methods have enabled the identification of less severe forms of diseases or disorders. It is becoming clearer that a substantial proportion of these earlier 'abnormalities' will never progress, raising awkward questions about exactly when to use diagnostic labels and therapeutic approaches traditionally deployed against much more serious forms of disease," they added.

Other drivers are commercial and professional vested interests, conflicted panels producing expanded disease definitions and writing guidelines, legal incentives that punish underdiagnosis but not overdiagnosis, health system incentives favoring more tests and treatments, cultural beliefs that more is better, and faith in early detection unmodified by its risks, the authors stated.

"The industries that benefit from expanded markets for tests and treatments hold wide-reaching influence within the medical profession and wider society, through financial ties with professional and patient groups and funding of direct-to-consumer advertising, research foundations, disease awareness campaigns, and medical education. Most importantly, the members of panels that write disease definitions or treatment thresholds often have financial ties to companies that stand to gain from expanded markets," they wrote.

They advocate the development of a range of training curriculums and information packages to raise awareness about the risks, particularly associated with screening. New clinical protocols are necessary to bring more caution in treating incidentalomas, including raising the thresholds that define abnormal -- e.g., in breast cancer screening. Evaluate methods of observing changes to some suspected pathologies over time, rather than intervening immediately, also should be considered, they noted.

"Concern about overdiagnosis does not preclude awareness that many people miss out on much needed healthcare. On the contrary, resources wasted on unnecessary care can be much better spent treating and preventing genuine illness. The challenge is to work out which is which, and to produce and disseminate evidence to help us all make more informed decisions about when a diagnosis might do us more good than harm," the authors concluded.