Skier's thumb can be diagnosed based solely on clinical findings by residents in the emergency room (ER) when instructed correctly. Additional imaging such as MRI should only be employed in cases when the physical exam remains inconclusive, according to research from the Netherlands published on 21 July in the European Journal of Radiology.

In the prospective study, residents in the ER were given instructions for diagnosing skier's thumb based upon a physical exam. Patients with suspected skier's thumb were followed up with MRI that was reported by two experienced radiologists to confirm the diagnosis. The research team, led by Dr. Mandhkani Mahajan from the department of surgery at Medical Center Haaglanden in The Hague, found that patient history and a physical exam are indeed sufficient for diagnosing skier's thumb (EJR, 21 July 2016).

"Our study suggests that patient history combined with clinical examination of a skier's thumb performed by a correctly instructed resident should be sufficient to diagnose a true skier's thumb," the study authors wrote. "Additional imaging such as MRI is very accurate with excellent interrater agreement but should be reserved for cases in which clinical examination remains inconclusive."

What is skier's thumb?

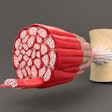

Skier's thumb is an acute rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. It occurs when a thumb, which is already in abduction, receives extra valgus stress, according to the authors, who are all skiers themselves.

"The classic trauma mechanism is when a skier falls down while holding on to [the] skiing pole," they wrote. "However, this injury can also occur with people playing sports involving a ball or stick, falling from their bicycle when holding on to the handlebars, or simply falling on an outstretched thumb."

The injury can involve a partial or a complete rupture -- the difference of which affects treatment. A partial injury is treated conservatively with only cast immobilization; a complete injury is usually treated by surgical repair combined with cast immobilization. Thus, correct diagnosis is crucial.

The knowledge of how to perform and interpret the physical exam is often lacking in residents working in the ER and in nonskiing countries, as the skier's thumb is relatively uncommon. At the authors' teaching hospital of Medical Center Haaglanden, approximately 20 patients a year present with a complete rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament.

With these factors in mind -- and the knowledge a physical exam can be difficult due to natural variations in a person's right and left thumbs, swelling, pain, etc. -- the question becomes whether skier's thumb really can be diagnosed with just a clinical exam or if additional imaging is necessary to determine that diagnosis. It's a question Mahajan's team sought to answer.

The study

The researchers carried out a prospective cohort study at their large teaching hospital. They included all patients who presented in both the ER and outpatient clinics of surgery and orthopedics with a clinical suggestion of a complete ulnar collateral ligament tear.

Physicians who participated in the study were defined as residents in emergency medicine, general surgery, or orthopedic surgery, varying from first- to fifth-year residents, who worked in the ER and outpatient clinics during their shifts.

The researchers developed a five-step plan to clinically diagnose skier's thumb with additional background information on patients. New residents and ER doctors were continuously trained in diagnosing ulnar collateral ligament tears by repeated lectures and hands-on sessions. Pocket cards and posters with clear instructions were available in the ER and outpatient clinics during the whole course of the study.

First, a radiograph of the thumb was performed to exclude osseous avulsion fractures. When the radiograph was negative, the thumb was tested using the five-step plan. When the patient was suspected of having a complete rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament, the patient would receive a cast, and a 1.5-tesla MRI exam (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens Healthineers) was scheduled within three days.

Two specialized musculoskeletal radiologists, both with more than 20 years of radiology experience and who were responsible for all MR imaging in the hospital, blindly assessed the MR images within two days.

Of the 30 patients included in the study, 22 had a clear diagnosis of a complete ulnar collateral ligament rupture at clinical examination. Of this group, only seven patients were found not to have a firm end point. All these patients were shown to have a total rupture of the ligament on MRI, three of them (43%) had a Stener lesion.

A smaller group of patients (eight) were found to have inconclusive results, either because of too much swelling during clinical investigation or there was a bilateral (mild) degree of laxity. The interrater agreement of the two radiologists reviewing the MRIs was very good (85%).

"Most patients could correctly be diagnosed to have a true skier's thumb, i.e., a complete rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament, by patient history and clinical examination alone," the authors wrote. "These patients did not benefit from additional MR imaging."

For this study, the researchers focused on physicians who had less experience with identifying and treating skier's thumb than fully trained hand surgeons. "We think that every intern or resident in surgery, orthopedics, or emergence care should be able to diagnose this injury," they wrote.

Also, they wanted to mimic a real-life situation.

"Normally, a patient with this type of injury will go to the emergency department and is investigated by a junior physician with less experience," the authors wrote. "This is also the reason why the patients were not re-examined by an experienced surgeon, because in reality this rarely happens. This makes our study a true reflection of the current situation and, therefore, its results are useful to implement in daily practice."

As a result of this study, more patients are being identified with a skier's thumb than in the last few years, Mahajan told AuntMinnieEurope.com.

"It has raised awareness of this condition in our hospitals," she said.

Future planned research includes follow-up MRI of conservatively treated patients with skier's thumb to image the way the thumb heals.

"We are also talking of perhaps starting to make both an MRI and an ultrasound of the same patients to compare results," she added.