Paralympic athletes represent a particular challenge for imaging professionals, because they often have underlying physiological or structural abnormalities that take patient management and care to a new level, according to Dr. Rob Campbell, Paralympic imaging lead at the London 2012 Games.

The 2016 Paralympics will be held in Rio de Janeiro from 7 to 18 September, and several learned points from the Paralympic service at the London 2012 games are relevant, he said at a recent workshop in London, On the road to Rio: Hot topics in sports imaging, organized by the British Institute of Radiology in collaboration with AuntMinnieEurope.com. For instance, a major injury that would prevent an able-bodied athlete from performing might not affect a disabled one.

In the frame: Dr. Rob Campbell enjoys a lighter moment at London 2012.

In the frame: Dr. Rob Campbell enjoys a lighter moment at London 2012."If you have a relatively minor Achilles tendon injury in an able-bodied patient, versus a disabled athlete, then this is much more likely to affect the able-bodied athlete's ability to perform and the level at which they are going to perform," explained Campbell, a consultant radiologist at the Royal Liverpool & Broadgreen University Hospitals in Liverpool, U.K.

Many athletes have bone abnormalities or other underlying congenital anomalies, he added. For example, a Paralympic athlete who was a powerlifter who lies on the bench and lifts weights fell over in the 2012 Olympic Village. He was taken to a major London hospital, but was able to perform two days later because he did not need to use his legs but just his arms. Had he been an Olympic athlete it would been a major injury that would have prevented him from participating.

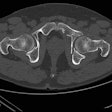

"Clinical evaluation can be difficult in these patients, and the pain may be poorly localized," Campbell said. "Our patient with osteogenesis imperfecta showed no fracture on x-ray, but a fracture was found on CT scan. In this case, the threshold for using CT imaging was lower."

Injuries in Paralympians need to be considered in a different light to injuries in the able-bodied, often concerning issues unrelated to imaging itself, Campbell noted.

"For instance, if you operate on the shoulder of a disabled athlete, they may be unable to use a wheelchair and lose their independence," he said.

In some respects, however, the athletes are similar to Olympic athletes in that they are elite and perform to a high level. In 2012, Campbell and his team saw a lot of muscle and tendon injuries similar to those seen at the Olympics. The key to ensuring elite Paralympic athletes can compete at their best is understanding the differences from the Olympic athlete, such as an underlying bone disease or something more logistical, such as treating the athlete's guide rather than the athlete themselves.

Injury distribution

Considerable research is ongoing into the types of injuries and how they influence Paralympic athletes' performance. The International Paralympic Committee has a medical committee that looks at injury outcomes, and in 2012 they put their first injury surveillance system in place to provide information on the nature of injuries at the games both in terms of the nature of the sport and the location of the injuries.

"Incidence of injury was roughly evenly distributed between the sexes, and, unsurprisingly, injury rates were lower in younger athletes. There was also a much larger age range in the Paralympics than the Olympics," Campbell reported. "Injury rates were similar precompetition as in competition, and just over half were acute injuries. Far from all injuries required imaging."

Injury surveillance is important, because it can have an influence on the way rules and regulations change, especially in emerging sports. A few years ago, in sled (aka sledge) hockey, medical staff noticed a high rate of lower limb injury. It was found that there was no regulation between the size of the sled and the player, and some sleds would injure other athletes. Since this recognition, all sled sizes are standard, he said.

| Imaging of injuries at the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games | |||

| Modality | No. of Olympians | No. of Paralympians | |

| MRI | 835 | 254 | |

| Diagnostic CT | 50 | 28 | |

| Diagnostic US | 347 | 157 | |

| Plain film | 405 | 216 | |

| CT-guided injection | 29 | 6 | |

| Ultrasound-guided injection | 45 | 11 | |

| Total | 1711 | 672 | |

Commenting on the range of scans performed in the Paralympics, Campbell noted that the imaging distribution was similar between Olympics and Paralympics, but the total volume was less. There were quite a few spinal injections in the Paralympics, but they tended to be chronic rather than acute problems. Distribution of disease by sport showed there were a lot of injured powerlifters, with smaller numbers of injuries in contact sports, basketball, and volleyball. Similar to the Olympics, the Paralympic imaging team saw a lot of tendon pathology, muscle tears, and quite a few fractures.

Surprisingly, many chronic injuries were managed without imaging, and numerous nonsporting injuries occurred around the village. Campbell said he was unsure why this was the case given that the village had good disabled access.

Service planning: 7 a.m. to 10 p.m.

The Paralympics features around 4,000 athletes from 164 countries and is significantly smaller in size than the Olympics, which has about 10,700 athletes from 205 countries, and this must be taken into account when planning the imaging service.

"We knew it would require fewer radiologists, but we still wanted to run the service from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m., so we needed a similar number of radiographers to keep the service going," said Campbell, who factored in longer appointment times for disabled athletes, especially for MRI scans to get the athletes in and out of the scanner.

Compared with the Olympics, there was also less need to prioritize athletes precompetition, in competition, and postcompetition due to less pressure on the service. This meant staff could give the athletes' guides the same priority as the athletes, which was important because an athlete is unable to compete if the guide is unwell or injured.

Involuntary movement

The imaging team also needed to accommodate for involuntary patient movement, which is specific to some Paralympic athletes -- for example in patients with cerebral palsy or paraplegic patients with muscle spasms.

"This is particularly relevant when we used MRI scanning, so we had a very low threshold for motion artifact reduction software, which made a big difference to the image quality, when there was any risk of involuntary movement," Campbell said.

A significant number of ex-military athletes also participated in the games, and this was associated with issues around embedded shrapnel, as well as some language issues with athletes from around the world.

"Sometimes the extent of injury was unclear, and we did not know how much metal work or implants were in the body. In these cases, rather than use x-ray, we chose to use CT scanning earlier than we normally would to see what was going on. In our setup, this was much quicker than sending the patient for x-ray," he commented.

Overall, Campbell said he was pleasantly surprised by how few medically related complications there were, at least in terms of the athletes who arrived for imaging. This was a reflection of how well these athletes were looked after, he concluded.