LONDON - Prolonged time away from competition can threaten an elite athlete's career, so everybody will welcome news that precisely grading muscle injury to facilitate a prognosis is a step closer after implementation of a new classification system, delegates learned at Friday's sports imaging workshop.

"An effective classification system allows the clinician to decide when the athlete can resume training and competition," said Dr. Steve James, consultant musculoskeletal radiologist at the Royal Orthopedic Hospital in Birmingham, U.K. "If they try to rehabilitate the athlete too quickly, there is a risk of reinjury, whereas if they are too conservative, the athlete loses training and competition time unnecessarily."

In a lecture at the London event On the road to Rio: Hot topics in sports imaging, organized by the British Institute of Radiology (BIR) in collaboration with AuntMinnieEurope.com, he discussed the latest muscle injury classification systems and the importance attached to the provision of both diagnostic accuracy and prognostic information, especially in the unique setting of the injured, elite athlete.

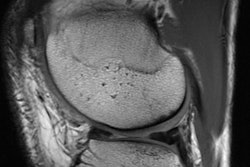

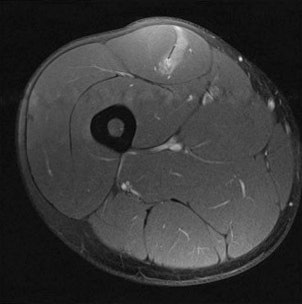

Axial fat-suppressed image demonstrates a muscle tendon junction injury to rectus femoris. Image courtesy of Dr. Steve James.

Axial fat-suppressed image demonstrates a muscle tendon junction injury to rectus femoris. Image courtesy of Dr. Steve James.In many cases, MRI scans can identify muscle injuries, but radiologists want to be able to provide an indication of the severity of the injury so the referring clinician can decide how long the athlete needs to refrain from sport to ensure satisfactory healing. Evidence about their ability to provide this information is mixed, according to James.

"We know the clinical assessment of strength does not correlate with prognosis," he said, adding that clinical examination does not provide an indication of rates of re-injury. "There clearly remains a problem with grading muscle injury clinically."

Bayern Munich's doctor

Muscle injuries are common in sport. The former club doctor of Bayern Munich Football Club said they constituted 31% of all injuries in elite football (Mueller-Wohlfahrt HW, British Journal of Sports Medicine, April 2013, Vol. 47:6, pp. 342-350), yet after decades of research, classification with respect to prognosis still requires refinement.

At the turn of the 20th century, understanding muscle injury consisted of internal (e.g., muscle strain) versus external forces (e.g., muscle contusion, as in rugby). Later attempts at anatomical descriptions provided the location of the injury, but there were limitations until the advent of cross-sectional imaging. In the 1980s, radiologists were able to directly visualize muscle injury, facilitating accurate descriptions of which muscle was involved. More recently, considerable investment and research were spent on predicting how long a player will be absent from training and competition.

Early descriptions of imaging reflected the clinical classifications, James pointed out. There were no real attempts between 1985 and 2000 to enable a prognosis to be given, and grades 1, 2, and 3 of imaging were considered to correlate to mild, moderate, and clinically severe. This grading system remains in use today.

Between 2002 and 2016, the features of muscle injury that confer a poor prognosis were explored in multiple studies. James explained aspects of injury that must be taken into account with this assessment, including length of lesion, extensive edema on MRI, tendon involvement, and higher cross-sectional involvement -- all of which are considered to indicate a more significant injury and imply a slower return to play.

Dr. Steve James, from the Royal Orthopedic Hospital in Birmingham, U.K.

Dr. Steve James, from the Royal Orthopedic Hospital in Birmingham, U.K.With accumulating evidence, opinions on what comprises a poor prognosis began to change, and by the end of 2009, experts appreciated that tendon involvement was associated with a poor prognosis and lead to a slower return to play and this still stands today, James noted.

In 2012, the Mueller-Wohlfahrt consensus statement provided definitions of the terminology used in the field of muscle injuries, as well as a new comprehensive classification system to define types of injury. This system suggested a relationship between injury category, prognosis, and return to play. According to James, the Mueller-Wohlfahrt consensus statement caused a stir in sports medicine, and following this, a number of sports physicians and radiologists were prompted to expand the Peetrons system of classification on ultrasound to include what they believed was important.

"There is further evidence emerging to suggest this class system is relevant," he added.

British athletics' classification

Most recently in 2014, a new grading system known as the British athletics muscle injury classification was introduced. This uses some current evidence based on tendon involvement, longitudinal length of injury, and cross-sectional area to propose another system to classify muscle injury. Injuries are graded 0 to 4 based on MRI features. The grades 0 to 4 have an additional suffix of a, b, or c if the injury is myofascial, musculo-tendinous, or intratendinous. This system is routinely used by a small but growing number of clinicians.

"The evidence on prognostication for this system was published in 2016 so it is a relatively new system. It differs [from older classification systems] in that it incorporates some of the newer evidence regarding features on imaging that have been shown to imply a poorer prognosis, that is a slower return to play," James said.

The British athletics muscle injury classification has been validated with inter- and intraobserver variability and as such it is reproducible, he explained.

"This year we've looked at the prognosis of injury, looking at speed at which the athletes return to their sport and we confirmed evidence from the literature, that is tendon involvement is important, muscle tear involving tendon means a longer time to return to play, and higher re-injury rate," James said. "Furthermore, a greater longitudinal extent of injury correlates with a longer return to play."

He also pointed out their system agreed with more recent evidence that the muscle affected does not impact prognosis, nor does location whether proximal, middle, or distal.

One of the most recent developments from James and his colleagues (Drs. Mark Davies and Rajesh Botchu) at the Royal Orthopedic Hospital in Birmingham is an app called MSKradiology4u (www.mskradiology4u.co.uk). It has a worldwide base and received more than 10,000 page visits in the first month after launch, and is recognized as a teaching resource with more than 3,000 cases that brings interactive radiology teaching into the 21st century.

"Users can use their phone, tablet, or PC to browse cases, and can search by anatomic location or diagnosis if they want to see specific pathology. If necessary, further information on cases can be provided via Google analytics," James said.