The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)’s newly published final recommendations support breast cancer screening beginning in women at age 40, but they don’t go as far as many screening advocates had hoped.

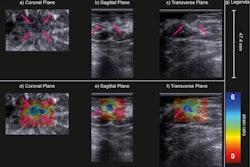

In addition to recommending biennial breast cancer screening for women ages 40 to 74, the task force stuck with its draft recommendations from 2023, reporting that it found insufficient evidence for screening women 75 and older. What’s more, the USPSTF concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend supplemental screening with MRI or ultrasound in women, regardless of breast density.

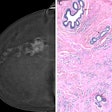

In announcing its new recommendations April 30 in JAMA, the USPSTF said that the evidence is sufficient that biennial screening mammography, rather than annual scans or personalized screening decisions, offers moderate net benefit in women ages 40-74. The task force categorized this recommendation as Grade B, which indicates its belief there is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.

The decision marks a return of sorts to the task force's 2002 breast cancer screening recommendations, in which the UPSTF recommended that women receive annual or biennial screening beginning at 40. In its 2009 recommendations, the task force chose instead to recommend that women receive biennial screening at the age of 50 and kept to that position when updating its recommendations in 2016.

The USPSTF provided a grade of I (insufficient evidence to make a recommendation) for screening of women over 75 or supplemental screening and also for supplemental screening in women with dense breasts. This grade indicates that the USPSTF believes that when these services are offered, patients should understand the uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms.

Dissenting views

The USPSTF's recommendations differ with many professional organizations, such as the American College of Radiology (ACR), Society of Breast Imaging (SBI), the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). In updated guidance in 2023, the ACR and SBI recommend that women at average risk for breast cancer receive annual screening mammography beginning at 40 and that screening should continue without an upper age limit. They also recommend that women -- and especially Black and Ashkenazi Jewish women -- receive a breast cancer risk workup by the age of 25.

The ACR also calls for women with genetics-based increased risk, those with a calculated lifetime risk of 20% or more, and those exposed to chest radiation at a young age receive MRI surveillance starting at ages 25 to 30. Furthermore, these women should also begin annual mammography at ages 25 to 40.

In addition, the ACR recommends that women diagnosed with breast cancer prior to age 50 or with a personal history of breast cancer and dense breasts should have annual supplemental breast MRI. Furthermore, high-risk women who desire supplemental screening -- but cannot undergo MRI -- should consider contrast-enhanced mammography, according to the ACR.

The ACR and the American Cancer Society have released statements on the new USPSTF recommendations.

Decision points

In an interview with AuntMinnie.com, Carol Mangione, MD, former chair of the USPSTF and current chief of general internal medicine and health services research at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), explained how the task force decided on its new recommendations and how the new recommendations compare to its 2016 recommendations.

Former USPSTF Chair Carol Mangione, MD, explains the recommendations and responds to critics

"We have no randomized trials of annual versus biannual screening," Mangione said, citing a lack of contemporary data that incorporates newer technologies used today. Also, "we need randomized trials of supplemental testing, both ultrasound and MRI, and we need multiple rounds of follow-up, and we need follow-up so that the vast majority of women randomized are followed long term. We've adopted a strategy where we're being much more transparent about the types of studies we need."

The USPSTF noted in the JAMA article that it performed a systematic review of evidence and also used models with data inputs from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) in its assessment. The BCSC is a network of six breast imaging registries and two historic registries.

"Available evidence suggests that biennial screening has a more favorable trade-off of benefits vs harms than annual screening," the task force wrote. "BCSC data showed no difference in detection of cancers stage IIB or higher and cancers with less favorable prognostic characteristics with annual vs biennial screening interval for any age group, and modeling data estimate that biennial screening has a more favorable balance of benefits to harms (eg, life-years gained or breast cancer deaths averted per false-positive result) compared with annual screening."

Evidence report, modeling

The USPSTF's 2024 breast cancer screening recommendations came with an evidence report and modeling study. USPSTF included people who have factors associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, such as a family history of breast cancer (i.e., a first-degree relative with breast cancer) or having dense breasts.

Although the task force acknowledged that dense breasts are associated with both reduced sensitivity and specificity on mammography and with an increased risk of breast cancer, it determined that there was insufficient evidence that supplemental screening with breast MRI or ultrasound has an effect on breast cancer morbidity and mortality in this patient group.

"... increased breast density itself is not associated with higher breast cancer mortality among women diagnosed with breast cancer, after adjustment for stage, treatment, method of detection, and other risk factors, according to data from the BCSC," the task force wrote.

Mangione said that the breast density issue is very important, however.

"Women who get that report saying they have dense breasts and that the mammogram doesn't work as well for them are kind of left in a little bit of a quandary," she told AuntMinnie.com. "We really want people to speak to their primary care doctor, speak to their radiologist and make a joint decision about for their individual situation."

The USPSTF said that its new recommendations don't apply to people who have a genetic marker or syndrome associated with a high risk of breast cancer (e.g., BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic variation), a history of high-dose radiation therapy to the chest at a young age, or previous breast cancer or a high-risk breast lesion on previous biopsies.

"Of note, the USPSTF has a separate recommendation on risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer, and family history is a common feature of risk assessment tools that help determine likelihood of BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic variation," the JAMA article pointed out.

In terms of risk-based screening, "the USPSTF found no evidence on the benefits or harms of individualized breast cancer screening based on risk factors. Several randomized trials of risk-based screening are underway (e.g., the WISDOM trial) that may provide valuable information regarding this question," the authors wrote..

Falls short?

Two editorials were also published in JAMA to coincide with the USPSTF statement April 30, one that addressed equitable breast cancer outcomes (tagging AI), and another that suggested the guidelines simply do not go far enough.

In an interview with AuntMinnie.com, Wendie Berg, MD, PhD, in the department of radiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and UPMC Magee-Women's Hospital, said the new breast cancer screening recommendations come up short and that the biennial screening intervals are surprising.

"Annual screening is particularly important for premenopausal women, especially women in racial and ethnic minority groups," Berg wrote in an accompanying editorial. In addition, "regular risk assessment should commence at age 25 years to identify women at high risk who should start annual MRI screening."

Wendie Berg, MD, PhD, on where the new breast cancer screenings fall short

Berg added that dense breast risks were minimized by USPSTF, noting the start (September 10) of a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirement that all women having mammograms receive notice that their breasts are dense or not dense. Berg helped develop DenseBreast-info.org to help educate patients and providers about dense breasts and appropriate dense breast screening beyond mammography alone.

"Women will further be notified that there is the potential that additional tests could help find cancer that might be not seen on the mammogram, so we really need guidance, and the Task Force failed to give that guidance," Berg explained, pointing to "very strong evidence" from a prospective randomized trial in the Netherlands that could have helped steer the course.

"The European Society of Breast Imaging in 2022 issued new guidance that said, explicitly, women with extremely dense breasts should have an MRI at least every two to four years," Berg said, adding that MRI is more effective at finding additional cancers in all populations of women. "In fact, it's cost-effective, it reduces aggressive treatment, and modeling indicates MRI reduces deaths from breast cancer. Moreover, the new EUSOBI guidelines also restate that recommendation to have an MRI at least every four years in women who have extremely dense breasts and really every two years if you can get it ... if you can't tolerate an MRI, then ultrasound should be considered."

Berg added that at least half of U.S. states have individual state laws requiring insurance to cover supplemental screening in women with dense breasts, although insurance coverage can be confusing from state to state.

"Many patients now unfortunately are falling into this patchwork of laws where they may or may not be able to access from insurance standpoint the supplemental screening that they need and we need to fix that," Berg added. "At the federal level, there is the Find It Early Act, that was introduced into Congress in 2022, again in 2023, and will need to be reintroduced again next year, that everyone should support, which would require a uniform standard of insurance coverage linked to national guidelines for supplemental screening, including the American College of Radiology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network."

Disparities considered

One major impetus for lowering the recommended breast cancer screening start age to 40 stems from the need to tackle disparities affecting specific subpopulations, according to Joann Elmore, MD, of the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, and Christoph Lee, MD, in the department of radiology at University of Washington School of Medicine and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle. Elmore and Lee penned one of the two featured editorials tied to USPSTF's 2024 breast cancer screening statement.

Mortality from breast cancer is highest for Black women, even when accounting for differences in age and stage at diagnosis, USPSTF noted. This is likely due to delays and inadequacies in the diagnostic and treatment pathway downstream from screening.

For Black women, expanding biennial digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) screening to women aged 40 to 49 (i.e., starting a decade earlier) has the potential to avert 1.8 additional breast cancer deaths per 1000 (compared with 1.3 in all women), Elmore and Lee wrote. They, too, raised the issue of dense breasts, saying there is an urgent need for better evidence on the topic of supplemental screening with ultrasound or MRI for women with dense breasts.

Elmore and Lee also added an important note about AI. "Historically, millions of U.S. women underwent screening mammograms with older, pre-AI computer-aided detection tools for nearly 2 decades before population-level studies revealed decreased accuracy when these tools were used," Elmore and Lee continued. "This historical error provides a clear warning that larger studies are required before wide adoption of newer AI tools for mammography."

Overall, "it is important that physicians continue to practice the art of medicine to ensure that women make informed decisions aligned with their preferences," wrote Elmore and Lee.

More studies

The updated USPSTF recommendations highlight a rapidly evolving intersection of technology and equity, breast cancer screening advocates said in relation to the 2024 recommendations. While they were informed by the evidence, the USPSTF said that there are critical evidence gaps that must be addressed through further studies. A few directions the USPSTF highlighted include:

- Research is needed to determine whether the benefits differ for annual vs biennial breast cancer screening among women overall and whether there is a different balance of benefits and harms among Black women compared with all women.

- Research is needed to determine the benefits and harms of supplemental screening (e.g., ultrasonography, MRI, or contrast-enhanced mammography) compared with usual care (DBT or digital mammography alone) for women with dense breasts. Studies are needed that report outcomes such as the rates of advanced breast cancers diagnosed across consecutive screening rounds in addition to the rates of diagnosis of breast cancer, and health outcomes such as quality of life and breast cancer-associated morbidity and mortality.

- Research is needed to identify approaches to reduce the risk of overtreatment of breast lesions identified through screening that may not be destined to cause morbidity and mortality. Include the natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and identify prognostic indicators to distinguish DCIS that is unlikely to progress to invasive breast cancer.

- Research is needed to understand and address the higher breast cancer mortality among Black women, including biomarker patterns that confer greater risk for poor health outcomes; variations in care across the spectrum of stages and biomarker patterns and effective strategies to reduce disparities; and to determine whether the benefits differ for annual versus biennial breast cancer screening among women overall and whether there is a different balance of benefits and harms among Black women compared with all women.

Mangione added that the USPSTF offers details on specific populations the task force wants to see studied.