Routine breast cancer screening should not be performed on a large scale in women older than age 70 until more data are available, according to Dutch researchers who conducted a trial of more than 38,000 women and published their findings online on 15 September in BMJ.

But the prospective study has attracted angry responses from breast imaging experts Dr. Daniel Kopans, from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and also Dr. László Tabár, from Falun Central Hospital in Sweden.

Breast cancer screening has seen its share of debate. Some say it causes overdiagnosis, while others say the overdiagnosis risk is worth it due to the lives saved. Even for those who stand behind screening mammography, another debate is whether to screen annually or biennially. Once that's been figured out, there's also the question as to what ages to include.

National breast cancer screening programs' cut-off point is anywhere from age 69 to age 75, and most randomized controlled trials stop at age 60, meaning it's unclear whether screening is beneficial for these older women, wrote Dr. Nienke de Glas, also a doctoral candidate, from the departments of surgery as well as gerontology and geriatric at Leiden University Medical Center in Leiden, the Netherlands, and colleagues (BMJ, 15 September 2014).

"Although trial data on screening in older women are lacking, some observational studies hint at a beneficial effect on mortality rates in this age group," they wrote.

To determine whether older women benefit from breast cancer screening, a trial that investigates the incidence rates of advanced stage cancers in these older women is necessary and must come from a screening population, the authors added.

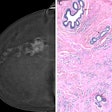

"If a screening program is effective, it can be expected that the incidence of advanced stage cancer decreases, while the incidence of early stage breast cancer increases," they wrote. "This approach is not affected by confounding factors that are often present in observational studies on the effects of screening on mortality rates."

The researchers investigated just that -- the incidence of early stage and advanced stage breast cancer before and after implementation of the Dutch national screening program in women of 70 to 75 years. They found extending the upper age limit to 75 years did not result in a strong decrease in incidence of advanced breast cancer, whereas the incidence of early-stage breast cancer strongly increased in patients of 70 to 75 years.

Study methods

The researchers selected all patients of 70 to 75 years with a diagnosis of invasive and ductal carcinoma in situ breast cancer between 1995 and 2011 from the Netherlands cancer registry. Overall, the study included 25,414 patients of 70 to 75 years and 13,028 patients of 76 to 80 years. In both age groups, most patients had a diagnosis of stage I or II breast cancer.

The researchers sectioned the study into three periods: a period before screening (1995-1997), a screening uptake period of five years to prevent bias from a too-short period (1998-2002), and a period after implementing screening (2003-2011).

In women of 76 to 80 years, the incidence of early-stage breast cancer slightly decreased, while the incidence rate did not significantly change in the evaluated time frame.

| Incidence of cancers before and after screening | |||

| Incidence before 1998 | Incidence after 2003 | Incidence rate ratio before 1998 and after 2003 | |

| Early-stage breast cancers in ages 70-75 | 248.7 cases per 100,000 women | 362.9 cases per 100,000 women | 1.0 (reference) to 1.46 |

| Advanced-stage breast cancer in ages 70-75 | 58.6 cases per 100,000 women | 51.8 cases per 100,000 women | 1.0 (reference) to 0.88 |

| Early-stage breast cancer in ages 76-80 | 253.9 cases per 100,000 women | 212.4 cases per 100,000 | 1.0 (reference) to 0.84 |

| Advanced-stage breast cancer in ages 76-80 | 66 cases per 100,000 | 67.2 cases per 100,000 | 1.0 (reference) to 1.02 |

Upon further analysis, the incidence rate ratios in both age groups were similar to those in women 70 to 75 years old. The incidence increased by 114.2 cases per 100,000 women, whereas the incidence of advanced stage tumors decreased by 6.8 cases per 100,000 women. The ratio of advanced and early stage tumors was 19.7 (114.2/6.8) cases per 100,000 women per year.

"The strong decrease in advanced stage breast cancer that should be observed in a successful screening program remained absent in our data," they wrote. "This means that for every advanced stage tumor that was prevented by screening, 19.7 'extra' early stage tumors were diagnosed. ... This implies that mass screening in women aged 70-75 years leads to a considerable proportion of tumors that are overdiagnosed," they added.

Experts weigh in

Breast screening advocates are calling the paper another example of "failed peer review" at BMJ.

"Their first error is the assumption that if the rate of advanced cancers is not reduced, then screening has little effect," wrote Dr. Daniel Kopans in an email to AuntMinnieEurope.com. "This was shown years ago to be untrue. Screening can reduce deaths by reducing the size of cancers within stages."

Dr. Daniel Kopans.

Dr. Daniel Kopans.

Another problem with the study is the authors are estimating what the number of cancers would be each year (incidence) had there not been any breast cancer screening, wrote Kopans, a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School and a senior radiologist in the department of radiology, breast imaging division, at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Based on the guesses, they authors are suggesting many more cancers were diagnosed in the screening period than they "guesstimated" would have occurred without screening, he added.

"They concluded that the difference was cancers that would have never become clinically significant and were 'overdiagnosed' because of screening," he wrote. "In addition, because they claimed to see little decline in the number of invasive cancers with the introduction of screening, they concluded that the number of advanced cancers had not been decreased by very much based on screening."

The key flaw in the study comes down to the prescreening period, according to Kopans. De Glas and colleagues compared the number of cancers detected in 2011 with the number they guessed would have been diagnosed had there not been any screening by extrapolating this baseline. The authors then concluded the difference were cancers that would have never become clinically evident, were nonlethal, and, hence, were overdiagnosed.

"The argument is completely reliant on their guess as to what the incidence would have been had there not been any screening in the Netherlands," Kopans wrote. "The authors do not provide any data on how much screening was occurring prior to the national program. ... Regardless, the 'prescreening' numbers are completely insufficient to predict what the incidence would have been had the screening program not begun."

The authors also assume that in the absence of screening there would have been the same number of cancers diagnosed in 2011 as in 1996. Because there were many more than what they guessed should have been, the difference between what they guessed and the real numbers "must be cancers that would have never become clinically evident and were ovediagnosed," he added.

De Glas and colleagues are concerned about overdiagnosis and overtreatment because they said it could have an effect on quality of life and physical function of older women with breast cancer, as they are at increased risk of adverse outcomes of breast cancer treatment.

"Consequently, from a certain age the unfavorable effects of screening may outweigh the benefits," they wrote. "Moreover, the additional costs of treating overdiagnosed tumors could result in a tremendous increase in health expenditure as a result of the screening program, with no actual health benefits."

Tabár's view

Another breast cancer screening advocate, Dr. László Tabár, a radiologist at Falun Central Hospital in Sweden, agrees with Kopans' assessments.

"The authors of this article from the Netherlands have joined the group of authors who question the positive impact of early detection on advanced cancer rate by repeating the same mistake that we have critiqued so many times; the Dutch colleagues, just like all the other antiscreening authors lack precise knowledge about each tumor's detection mode: They do not know whether the cancers were detected at screening, in the interscreening interval or whether they were detected outside screening by the patient or her physician," he wrote in an email to AuntMinnieEurope.com.

Dr. László Tabár.

Dr. László Tabár.

He also pointed out that the Netherlands cancer registry registers anonymous population data, so cancers detected in women who attended screening (screen detected plus interval cases) and cancers that were detected outside screening cannot be distinguished.

"Thus, making claims that modern mammography screening has little or no effect in decreasing the advanced cancer rate (or reducing breast cancer death, as other authors concluded) is simply a biased guess," Tabár wrote.

It is certain the majority of the early-stage breast cancers in the Dutch study were detected among women who attended screening, he stated. And it is very likely the majority of the advanced stage breast cancers were patient- and physician-detected outside screening. If the large number of advanced cancers detected among the nonattendees was removed, the data would have shown the desired significant decrease in advanced breast cancer rate in women actually screened, he wrote.

"But this requires knowledge about 'detection mode,' which the authors do not have," Tabár added. "How many more articles will be published without access to accurate data on detection mode and sufficiently long follow-up? This type of poor research has been a recurring theme during the past decade, which harms women and confuses their physicians. This article should not have been published in a peer-reviewed journal."

More studies on breast cancer screening are coming. De Glas' team is keeping a close watch on a Cancer Research U.K. large, randomized controlled trial within the National Health Service (NHS) breast cancer screening program. The study will include women 71 to 73 years of age and the 70 to 73 years old age extension is randomly phased in, allowing the investigators to evaluate the effects of screening on breast cancer incidence and mortality, they wrote.

"Until the results of this trial become available, we propose that routine breast cancer screening in women aged more than 70 years should not be performed on a large scale," they concluded. "Instead, the harms and benefits of screening should be weighed on a personalized basis, taking remaining life expectancy, breast cancer risk, functional status, and patients' preferences into account."

Kopans does not agree. "Before potentially lifesaving interventions are withdrawn to save money, analyses should be based on the scientific evidence and not 'guesses,' particularly when those guesses are likely incorrect," he concluded.