Researchers from Spain have used PET to discover that individuals in their 50s with signs of cardiovascular disease also have reduced brain metabolism in areas connected with Alzheimer's disease. The findings provide a link between brain and heart health.

Researchers with the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) in Madrid used PET to examine over 500 individuals participating in the Progression of Early Subclinical Atherosclerosis (PESA) project. Directed by CNIC general director Dr. Valentin Fuster, PhD, the PESA study is following over 4,000 employees from Banco Santander in Spain to identify lifestyle and other risk factors that lead to atherosclerotic diseases.

In the current study, published online on 15 February in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, CNIC researchers led by first author Marta Cortes-Canteli, PhD, wanted to build on previous studies that found that elderly individuals with advanced stages of cognitive impairment also had higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors.

In particular, they wanted to know if cardiovascular risk factors like atherosclerosis were related to changes brain metabolism earlier in life.

They took a subgroup of 837 individuals participating in the PESA study, which is investigating the prevalence, progression, and determinants of subclinical atherosclerosis. Participants underwent upper-body FDG-PET scans between February 2013 and January 2015 with a hybrid PET/MRI scanner (Ingenuity, Philips Healthcare), and full-brain coverage was achieved in 547 individuals. Mean age of the participants was 50.3 years, and 82.5% were men.

Cardiovascular risk factors of the participants included dyslipidemia (60%), smoking (27.1%), hypertension (19.7%), and diabetes (4.6%). The median Framingham risk score of the group was 24.2%. Total plaque burden of the carotid and femoral arteries was 79.6 mm3, while the carotid plaque burden was 3.7 mm3 and the femoral burden was 46.2 mm3.

Researchers then analyzed whether there were any connections between the cardiovascular risk factors on the Framingham risk score and global cerebral FDG uptake based on standardized uptake value ratio (SUVr) on the PET scans. They found that individuals with higher Framingham scores had lower radiotracer uptake, with a beta of -0.15 (p < 0.001). Hypertension was the risk factor with the strongest association with reduced metabolism throughout the brain.

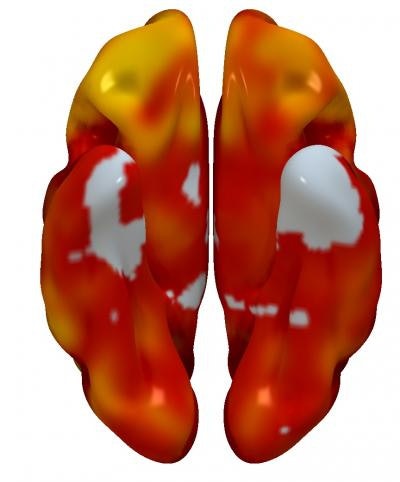

Additional analysis found that the areas of the brain with reduced FDG uptake were mostly in the parieto-temporal region, more specifically the angular and middle/inferior temporal gyri. The researchers even mapped individual risk factors to hypometabolism in specific brain regions, finding that systolic blood pressure affected reduced FDG uptake in areas like parahippocampal and inferior temporal gyri. These same areas are known to be the brain regions significantly affected by Alzheimer's disease.

3D reconstructions of superior (left) and inferior (right) brain regions, showing regions with lower metabolism associated with the presence of atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid arteries. The color code indicates the magnitude of the observation (yellow, strong association; red, lower association). Gray indicates areas showing no association with carotid plaque presence. Image courtesy of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC).

3D reconstructions of superior (left) and inferior (right) brain regions, showing regions with lower metabolism associated with the presence of atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid arteries. The color code indicates the magnitude of the observation (yellow, strong association; red, lower association). Gray indicates areas showing no association with carotid plaque presence. Image courtesy of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC).Finally, the researchers analyzed the connection between subclinical atherosclerosis and brain metabolism. They found no association between total atheroma burden and FDG uptake throughout the entire brain, but there were specific brain regions with lower metabolism that were associated with total plaque burden on a statistically significant basis.

Based on the findings, the researchers concluded that cardiovascular risk factors are associated with reduced global brain metabolism as measured by FDG-PET, and that hypertension was the primary driver of the association. Also, plaque burden in the carotid artery is associated with lower brain metabolism, and the areas of the brain affected by cardiovascular risk are known to be affected in dementia.

The researchers concluded that their study shows that the earliest stages of the development of cardiovascular risk factors could be affecting brain metabolism, and the brain regions being affected are also most impacted by Alzheimer's disease later in life. Addressing carotid blood flow in particular, they noted that other studies have shown that carotid stenosis has been linked to cognitive decline, a phenomenon that the PESA study may have detected at a much earlier stage.

"Although PESA study participants do not present carotid stenosis, we cannot discard that carotid plaque burden may be contributing to small changes in cerebral flow hemodynamics impacting brain metabolism," they wrote.