As Europe struggles to cope with the novel coronavirus outbreak, one doctor in Spain is using point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) to track his own COVID-19 disease. His findings echo those of other doctors on the front lines in showing that ultrasound can help with diagnosis, treatment, and admission decisions.

Dr. Yale Tung Chen, an emergency medicine physician at an academic hospital in Madrid, was diagnosed with COVID-19 following a rapid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test on 8 March. Like his patients, many of his first symptoms were mild -- a little worse than a common cold, he said during a 19 March webinar on POCUS for COVID-19.

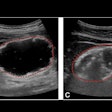

Chen's initial lung ultrasound scans appeared normal, too. However, in the days following his positive test result, lung sliding started to appear laterally on the ultrasound scan. He also saw some B-lines and thickening of the pleura. On day four, he noticed subpleural consolidations for the first time.

"As my disease progressed, the lower back started to clear, but then other spots were affected -- especially on the lateral sides, my axillary fossa, the scapular fossa," he said.

During this time, Chen's clinical symptoms, including fatigue and cough, would improve and then worsen again. The cyclical nature of his clinical symptoms matched what he saw on the ultrasound scans.

"[Lesions] on my back started to clear up, then reappeared a couple of days later," he said. "It's something that is quite different from any other viral pneumonia that we have faced in the past."

Now that he's more than a week out from his positive test result, Chen is doing well. His oxygen saturation never dropped below 95%, and he hasn't experienced dysthymia, shortness of breath, or chest pain.

He also performed cardiac imaging every two days but didn't find anything remarkable.

Ultrasound warning signs

Chen's findings on his own lung ultrasound scans mirror the findings of doctors in other European countries. Dr. Mike Stone, former division chief of emergency ultrasound at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston and head of education at POCUS developer Butterfly, noticed many hospitals in Italy are using lung ultrasound as a primary or secondary modality for patients with COVID-19.

The turn to ultrasound comes from a lack of resources for other types of chest imaging, such as CT, which from the start of the outbreak has demonstrated its utility in detecting COVID-19. And because POCUS can be used bedside, it avoids concerns about spreading the virus when patients are moved to different locations.

"There are many places currently using lung ultrasound as a primary imaging modality to try and address some of these concerns," Stone said during a 19 March webinar on POCUS for COVID-19.

In a normal lung ultrasound scan, ribs and shadows are evident with a pleural line that's bright and smooth, Stone noted. There are also A-lines, which are horizontal reverberation tracks from an air-filled lung.

But patients with COVID-19 tend to also exhibit focal B-lines along with spared, normal A-lines, also known as skip areas.

"Patchy B-lines and confluent B-lines," he said. "That's a pattern that we are seeing commonly in many of the images that have been sent to us over the last several weeks."

In addition, the ultrasound scans of patients with COVID-19 show a thickened pleural line. Patients can also have subpleural consolidation or traditional consolidation.

"You've got an area of almost solid organ-appearing tissue under the pleural line," Stone said. "You've got some air bronchograms. This isn't dissimilar from what you might see in bacterial pneumonia."

In COVID-19 patients, the findings also fluctuate and reoccur, as they did for Chen. Patients can have A-lines disappear, reappear a few days later, and then disappear again. Pleural consolidation can also wax and wane, according to Stone.

Ultrasound for triage

Stone polled lung ultrasound experts in his network to see how doctors in Spain, Italy, and other countries have used ultrasound systems to triage patients. While he cautioned that no doctor should be making admission or discharge decisions based solely on ultrasound scan findings, the doctors used ultrasound in similar ways.

For areas where rapid PCR testing is available, a patient with hypoxia and a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test is often admitted to the hospital's COVID-19 unit, with imaging left to the discretion of the treating provider.

"What I've heard repeatedly from physicians hardest hit in Italy is that in the COVID wards, when they make rounds, they'll come in and they'll scan their lungs," Stone said. "They'll scan their heart, looking for cardiac issues. They'll scan the [inferior vena cava] collapsibility to take care of all three of those assessments at one time with the single physician."

In areas where rapid PCR testing isn't available or where tests are running low, lung ultrasound is sometimes used as a secondary screening modality after patient presentation and COVID-19 risk factors.

For instance, Stone doesn't have access to rapid PCR testing, so he has been using ultrasound for patients with labored breathing.

"That's my trigger," he said. "Even if their oxygen saturations are normal, if they're feeling short of breath, I want to take a look at their lungs. That's how I'm making that decision right now."

Similarly, when Chen's wife complained of mild throat soreness a few days ago, he couldn't get access to a PCR test. So he scanned her back with POCUS instead.

"There were B-lines with the thickened pleura," he said. "I didn't need to do anything else. That was the positive result that I was waiting for."

Some patients who appear healthy can also have "ugly" ultrasound scan results. And while clinical symptoms, including hypoxia, tachycardia, and dyspnea, can lag behind ultrasound findings, that doesn't mean every patient with concerning ultrasound results needs to be admitted.

"Admission decisions are going to be based on patients who are tremendously ill," he said. "People with hypoxia, people with increased work of breathing who look unwell -- those patients are going to be coming in kind of regardless of what their lung ultrasound shows."

Too soon?

Stone stressed that there hasn't been time to do the kind of evidence-based, prospective studies the medical profession relies on. So, some of these recommendations will be quickly outdated.

Stone is collecting data based on his own experiences and those of other doctors using all types of ultrasound imaging systems in the fight against COVID-19. And so far, it's looking like lung ultrasonography may be a helpful tool -- and it's not hard to learn.

"The good news is that lung ultrasound -- as opposed to say echocardiography -- is really easily learned," he said. "The lung surface is very accessible. There aren't these tiny windows to work with. I have taught completely naive people how to look for lung sliding, A-lines, and B-lines successfully in less than a 30- or 40-minute session. So this is not challenging to learn."