Researchers from Norway are offering a theory for a puzzling question on the risks of heading a football -- why does the practice seem to affect female players more than their male counterparts? They believe the phenomenon could be related to the size and weight of the ball relative to player size.

A new editorial in Radiology speculates on why football heading causes more brain changes on MRI scans in women than men. A team from Norway speculates that because both sexes play with the same standard-sized ball, heading has a relatively greater effect on women.

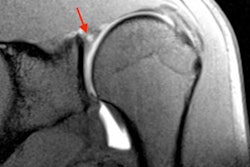

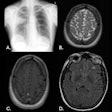

In an editorial published online on 8 January in Radiology, the researchers suggest the size and weight of the ball could influence why more microstructural white-matter changes are observed in the brain tissue of female football players who often use their heads to redirect the ball than their male counterparts.

The perspectives come from Prof. Arve Vorland Pedersen and Ragna Stalsberg at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and they follow a 2018 study by Rubin et al in which diffusion-tensor MRI was used to discover the disparity between the players in the effects of football heading.

Given that the men and women use footballs of the same size and weight, the pair suggest that the "relative impact due to sex differences in body size (notably, head mass) and neck anthropometry would be important for explaining the results of Mr. Rubin and colleagues." Thus, the "ball weight should receive more attention."

The editorial authors "articulate an intriguing mechanistic hypothesis" about how the "interaction of ball size with neck strength and anthropometrics may account for the sex differences we identified," wrote Dr. Michael Lipton, PhD, the lead author of the original study. Lipton is a professor of radiology, psychiatry, and behavioral sciences and neuroscience at Albert Einstein College in New York City.

Changing the mass of the football, he added, might not decrease the adverse effects of heading if "its kinetic energy increases as a result." Lipton recommended that any corrective actions be based on evidence from future studies to "minimize risk for unintended consequences."

"We, thus, agree with Mr. Pedersen and Ms. Stalsberg that prospective assessment of biomechanics-based interventions, such as ball design, is an intriguing target for future studies," he concluded.