New research published on 20 June demonstrated that while x-ray remains the most practical method for imaging the canopic jars left behind by ancient Egyptians, the real imaging king is CT. CT allowed the researchers to identify the jars' contents better than MRI or x-ray.

The researchers imaged four canopic jars with x-ray, CT, and MRI. Additionally, they performed imaging-databased volumetric calculations for quantitative assessment of the jar contents. CT provided the most information about the content of the jars, which were more consistent with small organ fragments rather than entire organs, as was hitherto assumed, according to a team led by Dr. Patrick Eppenberger from the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

Ancient Egyptian canopic jars on display in the Egyptian collection of the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb, Croatia. Photograph by Dr. Patrick Eppenberger, with kind permission of the Archaeological Museum.

Ancient Egyptian canopic jars on display in the Egyptian collection of the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb, Croatia. Photograph by Dr. Patrick Eppenberger, with kind permission of the Archaeological Museum."Radiological analysis of ancient Egyptian canopic jars by CT and MRI may, therefore, have made a significant contribution to a better understanding of ancient Egyptian mummification practice," the authors wrote (European Radiology Experimental, 20 June 2018).

Digging into canopic jars

Ancient Egyptians left behind not only mummies but canopic jars, which are dense vessels made of stone or ceramic. Egyptians used canopic jars between 2,700 and 300 B.C. to separately store and preserve the internal organs that needed to be removed from the body for the mummification procedure to avoid putrefaction yet were considered essential for the afterlife. The Egyptians considered the stomach, intestines, lungs, and liver to be essential organs.

"Paleoradiology, therefore, often becomes a complex task, requiring unconventional methods and a good understanding of the characteristics of bioarchaeological materials and possible taphonomic and/or postmortem alterations," Eppenberger and colleagues wrote. "In particular, the loss of water in such samples, which leads to an increased density, makes it difficult to distinguish between different types of tissues or nonorganic constituents."

Not to mention, substances used during mummification and embalming or later added during museum curation can also alter tissue radiological appearance.

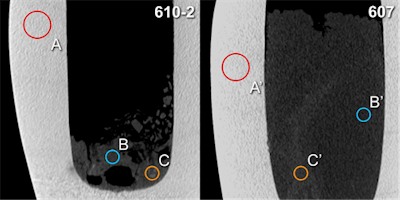

Hounsfield unit (HU) measurements: Analogous placement of regions of interest A and A' (calcite mineral), B and B' (surrounding material), C and C' (radiopaque structures) for two canopic jars (inventory numbers 610-2 and 607, respectively) on sagittal multiplanar CT scan reconstructions (slab thickness 1.5 mm). All images courtesy of Dr. Patrick Eppenberger.

Hounsfield unit (HU) measurements: Analogous placement of regions of interest A and A' (calcite mineral), B and B' (surrounding material), C and C' (radiopaque structures) for two canopic jars (inventory numbers 610-2 and 607, respectively) on sagittal multiplanar CT scan reconstructions (slab thickness 1.5 mm). All images courtesy of Dr. Patrick Eppenberger.The researchers performed the study as part of a larger transdisciplinary mummy research project linking medicine, evolutionary biology, and Egyptology. They performed basic noninvasive radiological procedures before further invasive procedures, such as sampling for histological, chemical, or genetic analysis. Radiology also helps museums' curators decide whether to open the jars or keep them untouched.

Especially as limited data on radiology and canopic jars exists, Eppenberger and colleagues sought to compare the potential and limitations of x-rays, CT, and MRI for examining canopic jars and the mummified visceral organs (putatively) contained within them. They also qualitatively and quantitatively assessed jar contents by CT-based density measurements and CT-based volumetric calculations.

Overall, CT scans provided the best diagnostic image quality (average rating of 2.75), followed by MRI (1.78) and x-ray imaging (1.72).

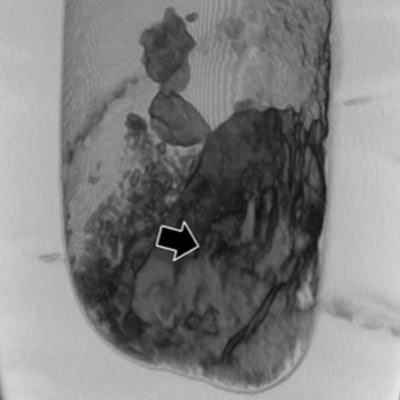

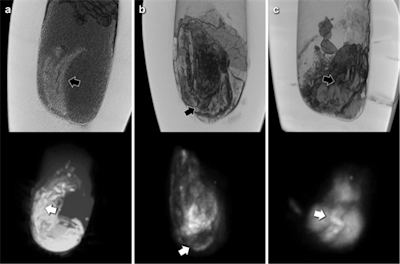

CT reconstructions (top) and correlative maximum intensity projections of MRI scans (bottom) of the three canopic jars with solid contents. Black arrows (CT) and white arrows (MRI) indicate corresponding structures of organ fragment like morphology, probably intestine.

CT reconstructions (top) and correlative maximum intensity projections of MRI scans (bottom) of the three canopic jars with solid contents. Black arrows (CT) and white arrows (MRI) indicate corresponding structures of organ fragment like morphology, probably intestine.The thickness and high density of the calcite mineral of the canopic jars limited x-ray image contrast. CT scans showed few artifacts and revealed hyperdense structures of organ-specific morphology, surrounded by a hypodense homogeneous material. CT scans revealed all the jars were partially filled with material of mostly heterogeneous density (mean 208 Hounsfield units [HU]).

In one jar (jar 607), structures of distinct longitudinal morphology and higher density (mean 344 HU, range from 71 HU to 595 HU) were clearly distinguishable from a homogeneous surrounding material of lower density (mean 186 HU, range from -88 HU to 448 HU).

The low amount of water present in the desiccated jar contents limited image quality of MRI scans. Nevertheless, areas of pronounced signal intensity coincided well with hyperdense structures previously identified on CT scans, according to the researchers. CT-based volumetric calculations revealed holding capacities of the jars of 626 cm3 to 1,319 cm3 and content volumes of 206 cm3 to 1,035 cm3.

"Although x-ray imaging often remains the most practical imaging modality for many paleoradiological applications (since it can be performed on site, for example at a museum or in the field, using portable equipment), for the purpose of this study it was but of limited value," the authors wrote. "The poor image quality can be explained as a result of the substantial thickness and rather high density of the calcite mineral composing the examined canopic jars (mean 2,215 HU), compared with the literature results for other minerals and nonmetallic materials."

The jar material did not much affect the CT scans, and, apart from slight beam hardening and cupping artifacts, no other masking effects could be found. Streaking artifacts were less of an issue due to the canopic jars' cylindrical shape with a nearly symmetrical distribution of high-density areas along the z-axis, the researchers noted.

The CT findings also raise the question of whether the examined canopic jars do hold entire mummified human organs. The structures identified in canopic jar 607 would be far more compatible with a small organ fragment (potentially intestine) rather than an entire mummified organ, they wrote. The MR images corroborate this, and the observed pronounced variations in signal intensity coincide very well with the organ fragment notion.

Further research will be necessary to determine the full capacity of MRI for canopic jars, the researchers concluded.