With each new publication, the high quality of cinematic rendering and its power for lifelike visualization of medical images continues to impress the radiology community. But studies demonstrating its usefulness in the clinical environment now must play catchup, according to researchers.

A new pictorial essay from the U.S. published online in the British Journal of Radiology on 22 September is the latest chapter in the discussion about how cinematic rendering could impact patient management.

Like many in the field of advanced visualization research, lead author Dr. Steven Rowe said the technique's exquisite detail and enhanced depiction of 3D anatomic relationships holds potential for improvements in diagnosis and interventional and surgical planning, but there's a long way to go before its routine use can be fully justified.

"We are now just on the cusp of figuring out cinematic rendering's specific clinical utility and all of the advantages and disadvantages relative to traditional 3D rendering techniques," Rowe told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "The technique is so new that many radiologists are unaware of its capabilities. Even those of us lucky enough to have access to these ... visualizations are still only beginning to realize the potential."

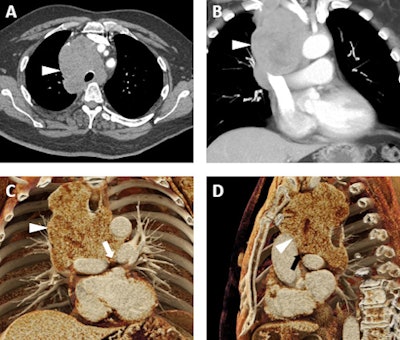

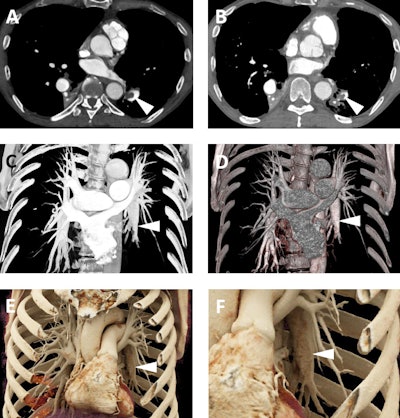

A 66-year-old man with a known diagnosis of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine tumor. A: Axial postcontrast 2D CT image demonstrates a confluent lymph node mass (white arrowhead) occupying much of the superior mediastinum with encasement of the trachea and interdigitation among multiple vascular structures. B: Volume-rendered image also demonstrates the mass (white arrowhead), which abuts and/or narrows the superior vena cava, the innominate veins, the aorta, and major arterial branches arising from the aortic arch, and the main, left, and right pulmonary arteries. C and D: Cinematic-rendered visualizations; the photorealism of these renders allows for the depiction of the tumor infiltrating between the left and right pulmonary arteries (white arrow in C) and between the ascending aorta and left pulmonary artery (black arrowhead in D). While this patient was not a surgical candidate, the added detail from cinematic rendering relative to other 3D techniques may prove quite valuable in surgical planning in regions of complex vascular anatomy. All images courtesy of Drs. Steven Rowe, Pamela Johnson, Elliot Fishman, and the British Journal of Radiology.

A 66-year-old man with a known diagnosis of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine tumor. A: Axial postcontrast 2D CT image demonstrates a confluent lymph node mass (white arrowhead) occupying much of the superior mediastinum with encasement of the trachea and interdigitation among multiple vascular structures. B: Volume-rendered image also demonstrates the mass (white arrowhead), which abuts and/or narrows the superior vena cava, the innominate veins, the aorta, and major arterial branches arising from the aortic arch, and the main, left, and right pulmonary arteries. C and D: Cinematic-rendered visualizations; the photorealism of these renders allows for the depiction of the tumor infiltrating between the left and right pulmonary arteries (white arrow in C) and between the ascending aorta and left pulmonary artery (black arrowhead in D). While this patient was not a surgical candidate, the added detail from cinematic rendering relative to other 3D techniques may prove quite valuable in surgical planning in regions of complex vascular anatomy. All images courtesy of Drs. Steven Rowe, Pamela Johnson, Elliot Fishman, and the British Journal of Radiology.For regions of complex anatomy, cinematic rendering is likely to be of great value to both diagnostic imaging specialists and vascular interventionalists who are determining patient treatment plans, according to Rowe, an assistant professor of radiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Furthermore, the cinematic-rendered images can facilitate patient education and informed consent by making disease processes easier to visualize and understand.

Case studies

To date, maximum intensity projection (MIP) and volume-rendered images both play a role in the preprocedure evaluation and postprocedure follow-up of endovascular patients. Cinematic rendering could prove to be a valuable asset for these cases, particularly given the continuing growth in catheter-based treatment to repair aortic aneurysm.

Specifically, a cinemetic rendering of the aorta ahead of such endovascular repair is likely to prove useful. In the figure below, a very narrow coarctation is depicted in high detail by cinematic-rendered images. The quality is sufficient to demonstrate this aortic pathology to patients, clearly showing them how the blood flow is compromised by the aortic constriction, as well as the mechanism of repair, the authors noted.

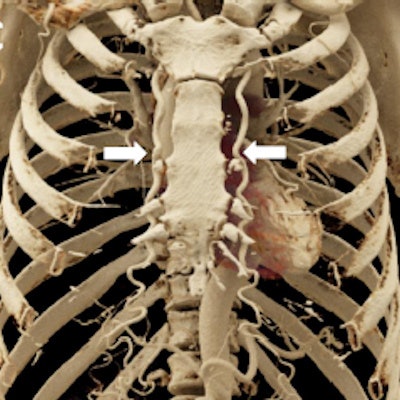

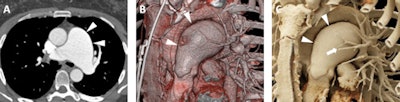

A 59-year-old man who was experiencing exercise intolerance and was found to have widely disparate upper and lower extremity blood pressures. A: Axial postcontrast 2D CT image demonstrates marked narrowing/coarctation of the aorta (white arrowhead) just distal to the takeoff of the left subclavian artery. B: Cinematic rendering image displays the coarctation in 3D (white arrowhead) with realistic shadowing effects and a detailed depiction of the relative positions of other vascular structures such as the immediately inferior left main pulmonary artery. C: Another cinematic-rendered visualization demonstrates representative collateral vessels (bilateral internal mammary arteries, white arrows).

A 59-year-old man who was experiencing exercise intolerance and was found to have widely disparate upper and lower extremity blood pressures. A: Axial postcontrast 2D CT image demonstrates marked narrowing/coarctation of the aorta (white arrowhead) just distal to the takeoff of the left subclavian artery. B: Cinematic rendering image displays the coarctation in 3D (white arrowhead) with realistic shadowing effects and a detailed depiction of the relative positions of other vascular structures such as the immediately inferior left main pulmonary artery. C: Another cinematic-rendered visualization demonstrates representative collateral vessels (bilateral internal mammary arteries, white arrows).Furthermore, although the data are not yet available to compare cinematic-rendered prosthetic valve evaluation with traditional evaluation with volume-rendered images, the new methodology may improve diagnosis of subtle complications, such as early bioprosthetic valve degeneration or the formation of small thrombi.

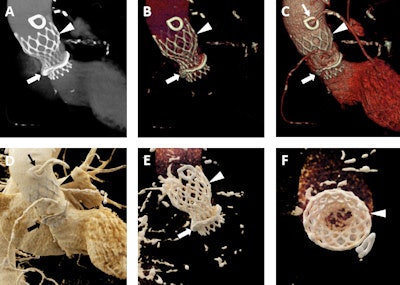

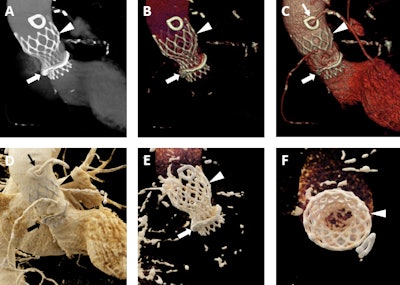

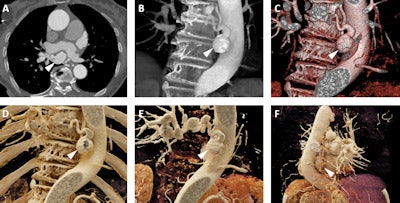

A 92-year-old man with a history of aortic stenosis initially treated with an open surgical procedure to place a bioprosthetic aortic valve and subsequently revised by endovascular replacement of a CoreValve. A-C: Volume-rendered images demonstrate the CoreValve (white arrowheads) inside the bioprosthetic valve (white arrows). The patient also has a patent saphenous vein-to-left anterior descending artery bypass graft (thin white arrow in C). D-F: Cinematic-rendered images also demonstrate the CoreValve (black arrowhead in D and white arrowheads in E and F) within the older bioprosthetic valve (black arrow in D and white arrow in E). The patient's patent saphenous vein graft is also apparent in D (thin black arrow). The photorealistic quality of the volume-rendered images may find eventual application in aiding vascular surgeons and other interventionalists by allowing the diagnosis of subtle thromboses or other valve-related pathologies that are not as apparent with less detailed visualizations.

Cinematic rendering also better visualizes chronic pulmonary embolism than does traditional volume rendering, possibly as a result of its capacity to discern the subtle textural difference associated with eccentric clots on the vessel wall, as demonstrated in the figure below.

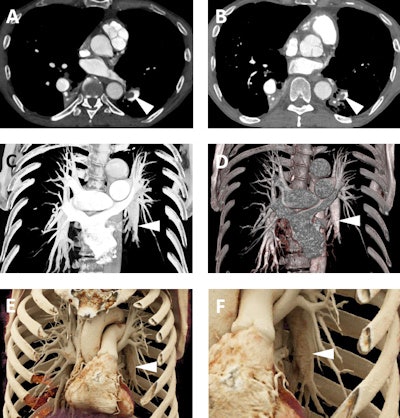

A 65-year-old man with a history of chronic thromboembolic disease. A and B: Axial postcontrast 2D CT images demonstrating eccentric filling defects in dilated left lower lobe pulmonary arterial branches (white arrowheads) compatible with chronic pulmonary embolism. C and D: Volume-rendered images demonstrate the dilated lower lobe pulmonary arteries (white arrowheads), although the eccentric filling defects from the clots are not well seen on these images. E and F: Cinematic rendering images (F is a blown up detail from E) again show the dilated lower lobe pulmonary arteries (white arrowheads), but due to the higher detail of cinematic rendering, there is a subtle textural change in the left lower lobar pulmonary artery (best seen in F) that is consistent with the patient's chronic pulmonary embolism.

Furthermore, it also provides highly detailed visualization of pulmonary arterial vascular conditions that may require surgical intervention such as pulmonary artery aneurysms.

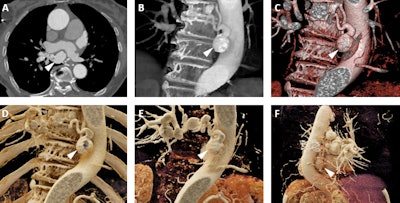

A 52-year-old woman with a history of pulmonary artery aneurysm of unknown etiology. A: Axial postcontrast 2D CT image demonstrates marked enlargement of the main pulmonary artery (measuring 5.2 cm, white arrowheads). B: Volume-rendered image also demonstrates the dilated main pulmonary artery (white arrowheads), with improved visualization of the relationship of the aneurysmal vessel relative to other vascular structures such as the aortic arch and the branching pulmonary vessels. C: Cinematic-rendered visualization once more shows the aneurysmal main pulmonary artery (white arrowheads) and its 3D relationship to other major vessels. The photorealistic detail and shadowing available with cinematic rendering creates high contrast that better highlights the smaller pulmonary vessels that overlie the main pulmonary artery in this view (white arrow).

A 52-year-old woman with a history of pulmonary artery aneurysm of unknown etiology. A: Axial postcontrast 2D CT image demonstrates marked enlargement of the main pulmonary artery (measuring 5.2 cm, white arrowheads). B: Volume-rendered image also demonstrates the dilated main pulmonary artery (white arrowheads), with improved visualization of the relationship of the aneurysmal vessel relative to other vascular structures such as the aortic arch and the branching pulmonary vessels. C: Cinematic-rendered visualization once more shows the aneurysmal main pulmonary artery (white arrowheads) and its 3D relationship to other major vessels. The photorealistic detail and shadowing available with cinematic rendering creates high contrast that better highlights the smaller pulmonary vessels that overlie the main pulmonary artery in this view (white arrow).The method's photorealistic shadowing effects provide accurate spatial information about small vessels within the complex branching pattern of the pulmonary vasculature near the pathologic structure.

"The same photorealistic shadowing can potentially obscure important structures, a potential pitfall in [cinematic rendering] that should be understood by both the interpreting image specialist and the referring clinician," the authors wrote in their essay.

Small vascular structures in the chest can also be evaluated with cinematic rendering to identify aberrant courses of coronary arteries and of aneurysmally dilated bronchial arteries.

Images from an 87-year-old woman who presented for follow-up of mild aneurysmal dilation of the ascending aorta. A: Axial postcontrast 2D CT image demonstrates dilated vascular structures in the mediastinum (white arrowhead). B and C: Volume-rendered images demonstrate another of these dilated vascular structures (white arrowheads), which in 3D are more apparently aneurysms of the bronchial arteries. D-F: Cinematic-rendered images again demonstrate the multiple bronchial artery aneurysms (white arrowheads depict the aneurysm that arises at the origin of one of the bronchial arteries from the descending aorta). This patient was not felt to be a candidate for any therapy of these lesions given significant comorbidities, and no cause for the bronchial artery aneurysms was ever uncovered. Nonetheless, the realistic shadowing provided by cinematic rendering and that is most apparent in F provides very clear representation of the relationships between the aneurysms and other structures, including the heart and descending aorta, and would be of value in surgical planning.

Because surgical intervention is necessary in some of these small-vessel pathologies, future studies should assess cinematic rendering's use in this presurgical context, the authors wrote.

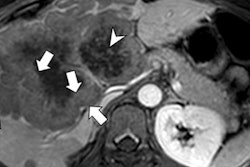

Treatment planning for tumors associated with major vascular structures also benefits from 3D visualizations. Cinematic rendering's capacity to display the relationship between masses and vessels shows great potential for future clinical implementation, the authors noted.

Rowe and co-authors Drs. Elliot Fishman and Pamela Johnson of Johns Hopkins are now focusing on pancreatic tumors -- and promise more papers on the topic in the future.

3D printing

While the role of cinematic rendering in 3D printing is yet to be investigated, the technique may contribute in two ways, according to Rowe. First, the photorealistic detail achievable may provide clinicians with information about anatomic structures, without the need to 3D print those structures for surgical planning, which would be a cost-saving strategy -- particularly in places where 3D printing is not reimbursed. Conversely, the same photorealistic detail and the relationship of structures conveyed in the cinematic-rendered images may aid in the construction and interpretation of 3D-printed models.

The high quality of cinematic renderings' 3D display and anatomic detail result from its unique lighting model.

Cinematic rendering uses a much more complex lighting model than volume rendering that more accurately depicts how light acts when coming into contact with real objects, the authors noted. Instead of the simple ray-casting method used for traditional volume rendering, the global lighting model in cinematic rendering incorporates information from thousands of light rays passing through the volumetric dataset and includes effects on those light rays from scatter and from voxels adjacent to the paths of the rays. The amount of information conveyed through this projection method into the final 3D image allows for a photorealistic level of detail not possible with other 3D reconstruction methods.

Given how well contrast-opacified vessels are seen, cardiovascular imaging is certainly one of the main applications for now. However, some of the most striking images come from skeletal cinematic rendering, according to Row.

"I think it is almost certain that cinematic rendering will become widely available in the near future. It is also almost certain that it will find inclusion in routine CT imaging for some applications," he said.

Studies needed

Several different kinds of studies should be undertaken, Rowe said.

"First, we should image various body phantoms with different objects inside them, then obtain a range of 3D images, including cinematic rendering, from the phantoms in order to compare the images with reality; namely, how closely the images resemble the physical objects inside the phantoms," he said.

Other studies involving different scoring systems, for example, R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry, also should be undertaken, with scores assigned by clinicians from cinematic-rendered images then compared with the findings at surgery.

Rowe further suggested future studies could include measuring postsurgery outcomes after patients have been randomized to either having cinematic rendering done preoperatively or not. However, he pointed out that surgeons may demand access to these images, making it hard to randomize patients in such a study.

Implementing studies that collate survey results that show how patients rate the acceptability of cinematic-rendered images and their usefulness in helping them understand their diseases and treatment plans also may be valuable.