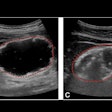

Bilateral breast ultrasound offers little or only marginal benefit in routine breast cancer screening for recalled patients, German researchers have found. In their study published online on 7 October in European Radiology, ultrasound detected unexpected breast cancer in dense breasts, but ultrasound-only cancer detection had a low positive predictive value.

"Quantitatively, there is not much evidence yet on the value of bilateral whole-breast ultrasound in the specific setting of recall regarding the detection of additional cases with breast cancer (person-specific) or breast sides with cancer (breast-specific)," wrote lead author Dr. Stefanie Weigel, from the Department of Clinical Radiology and Reference Center for Mammography at University Hospital Münster, and colleagues. "Qualitatively, it is unclear if one should either limit the ultrasound examination to the area with the screen-detected abnormality or examine both breasts."

Mammography is still the primary investigation for population-based breast cancer screening, but depending on several factors such as age and breast density, there can be a false-negative rate of 10% to 20%. Ultrasound is often used as an adjunct to detect breast cancers that were occult on mammograms in symptomatic and asymptomatic women. However, ultrasound may lead to more false-positive biopsies.

The European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis clarify the use of ultrasound as being used to characterize a lesion, stage breast cancer, and assist in guided biopsy. On recall, additional-view mammograms are used to verify or exclude breast cancer. If the mammogram comes back case-negative, bilateral whole-breast ultrasound may be used to further investigate.

The purpose of Weigel and colleagues' study was to determine the positive predictive value of incremental breast cancer detection (PPV1) and performed biopsies (PPV3) resulting from supplemental bilateral ultrasound examinations at recall of a population-based digital mammography screening program.

In their study of 2,803 recalled screening participants who had additional bilateral ultrasound, PPV1 of supplemental cancer detection by ultrasound only was 0.21%, compared with 13.8% by mammography.

"In other words, if a thousand women were to undergo ultrasound additionally to digital mammographic screening, this would lead to an incremental detection of only two additional women with breast cancer from the 1,000 who would have undergone ultrasound additionally," explained co-author Dr. Shoma Berkemeyer in an interview with AuntMinnieEurope.com.

The PPV1 of ultrasound-only cancer detection was 0%, 0.16%, 0.22%, and 1.06% for women with breast densities of ACR1, ACR2, ACR3, and ACR4, respectively.

The PPV3 of ultrasound-only lesion detection was 33.3 % compared with 38.0 % by mammography, the researchers found. The proportion of invasive cancers no larger than 10 mm was 37.5% for ultrasound-only detection, compared with 38.4% for mammographic detection.

"At a cancer detection rate of 0.93%, representative of a 'desirable level' according to European guidelines, our results demonstrated that supplemental ultrasound examination yielded a low PPV1 of 0.21% for diagnosing additional women with breast cancer over and above digital mammographic imaging, which had a PPV1 of 13.8%," the researchers wrote.

The use of digital mammographic techniques may have increased mammographic sensitivity among those women who had dense breasts, they cautioned.

"This might have contributed to the detection sensitivity in our unit, because usually some of these breast cancer lesions would not have been observable in images generated by screen-film mammographic techniques," they wrote.

This was further supported by the breast cancer detection rate of 9.3 per 1,000 screening participants at their screening unit, compared with an average annual breast cancer incidence of 2.6 per 1,000 women in the screening target population before the implementation of the population-based mammography screening program.

"The question emerges if less sensitive screening units' detection can be improved by additional qualitative assessment of breast density, e.g., by supplemental ultrasound, as part of future research work," the researchers wrote.

Strengths of the study include clearly defined screening and assessment workflow and the exclusive use of prospectively documented screening-related data. "Hence, sensitivity parameters, such as cancer detection rate, proportion of [ductal carcinoma in situ], and small invasive cancers, of our screening unit were well within 'reference values' defined by the European guidelines and representative of 'desirable values' of the European guidelines," they wrote.

Weaknesses of the study include not being able to calculate sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value of ultrasound and mammography as women with a false-negative assessment could not be determined.

"As a unique advantage in our area of operation, aggregated data of interval cancers covering the implementation phase could be provided by a data linkage process by the regional cancer registry," Weigel and colleagues wrote. "But at present, the strict data protection laws in Germany prohibit program participation identification via cancer registries, which rendered the calculation of the true-negative rate beyond our ability."

The researchers were also limited in that not all eligible participants (first and following rounds) took part in each round of the program, but a certain percentage would have reached the upper age limit of the screening investigation and fallen off of eligibility anyway.

Lastly, the results are limited because only one screening unit was included.

"For now, from both a psychological and medicolegal point of view, we will continue with the same practice at our institution," said Berkemeyer, from the same department at University Hospital Münster. "However, we will take this research even further and will report on interval cancer rates in screened women in the near future."

Additional ultrasound may lower the interval cancer rate of assessment participants, but from an economic perspective, systematic use of supplemental physician-performed ultrasound of both breasts after negative mammographic screening places a large burden on healthcare resources, especially if implemented in a population-based screening program, they wrote in their study.

Automated breast volume scanners may be an alternative to conventional handheld ultrasound, they noted.

Conventional handheld ultrasound takes 10 to 20 minutes with an experienced radiologist, and the practice of this in a large collective, such as screening, is in the long run almost impossible, Berkemeyer said.

"Additional studies, including follow-up of negative assessment participants and subgroup analysis based on breast density with greater numbers of examinations, are needed to optimize the use of bilateral ultrasound examination in this particular setting," the authors concluded.